Jan - Feb 2025 (Vol. 39, No. 3)

Nancy Nesvet

Daniel Benshana

Richard Vine

Elga Wimmer

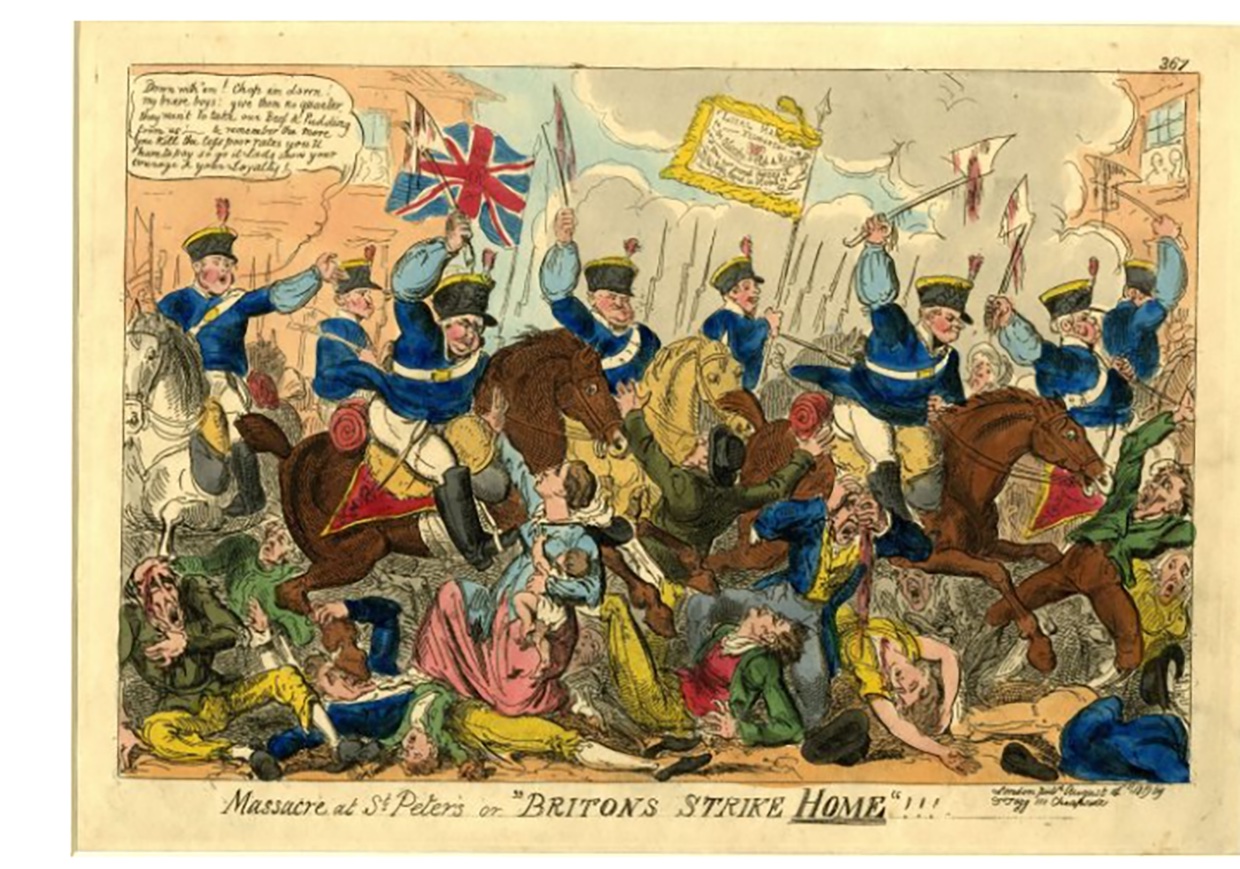

‘You’re Either with Me or Against Me’:The Lethal Morality Of Political Art

Jorge Benitez

Nancy Nesvet

Elizabeth Ashe

Speakeasy: With Darkness Came Stars’ a memoir

Mary Fletcher

The Korean Peninsula In Four Parts

Rina Oh

Isabella Chiadini

Nov - December 2024 (Vol. 39, No. 2)

Daniel Benshana

Minimal Effectiveness in Paris

David Goldenberg

Arte Povera: Art is its Own Family

Nancy Nesvet

Mary Fletcher

Paris and the Aesthetics of Complexity

Jorge Benitez

African Diaspora and Paris: Black Influence in 19th Century Modernism

Lanita Brooks-Colbert

From Revolution to Evolution : Paris 1874

Maryanne Pollock

Maria Balshaw, Director of the Tate

Sophie Kazan professor at Falmouth Art School

Rob Couteau author

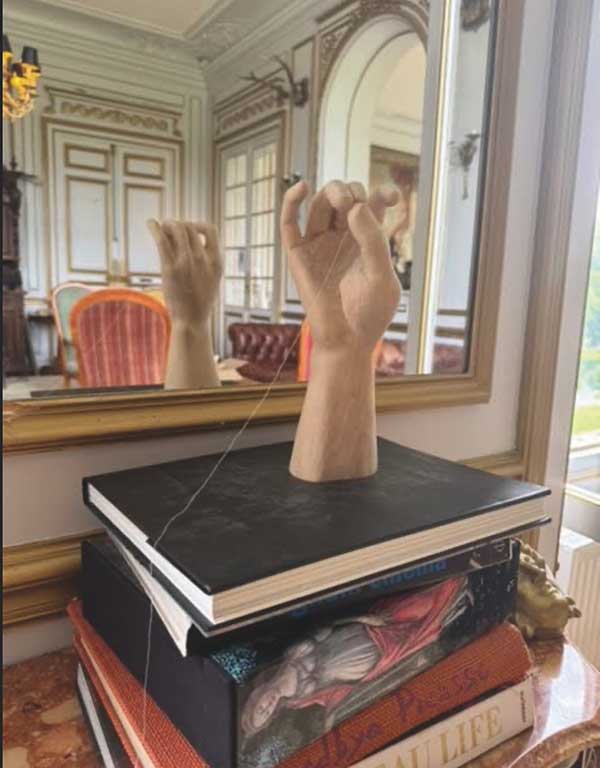

Elizabeth Ashe, sculptor

Taking a Pause to Breathe, to Be Still

Lorenzo Cardim

Annie Markovich

Sept-October 2024 (Vol. 39, No. 1)

Editorial – Dragons: The Legend Continues

Daniel Benshana

Compromise and Acceptance: The Game of Thrones and House of Dragons

Lanita K. Brooks-Colbert

Iconography of Dragons - Hobbits, Disney and More

David Goldenberg

“Healing the Earth” in the Wake of Joseph Beuys

Dr. Uranchimeg Tsultemin

Speakeasy: St. George and the Dragon

Daniel Benshana

Dragons in the Korean Royal Court

Rina Oh

Siegried Slays The Dragon Fafner

Jeanne Stanek

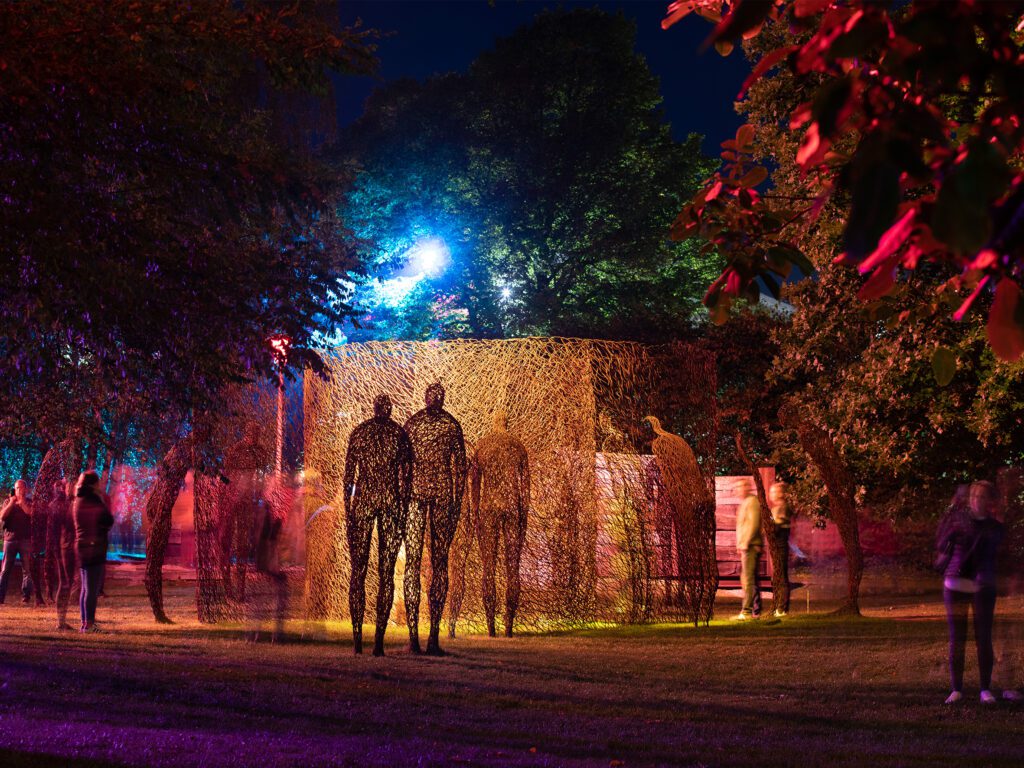

Elizabeth Ashe

July-August 2024 (Vol. 38, No. 6)

Nancy Nesvet

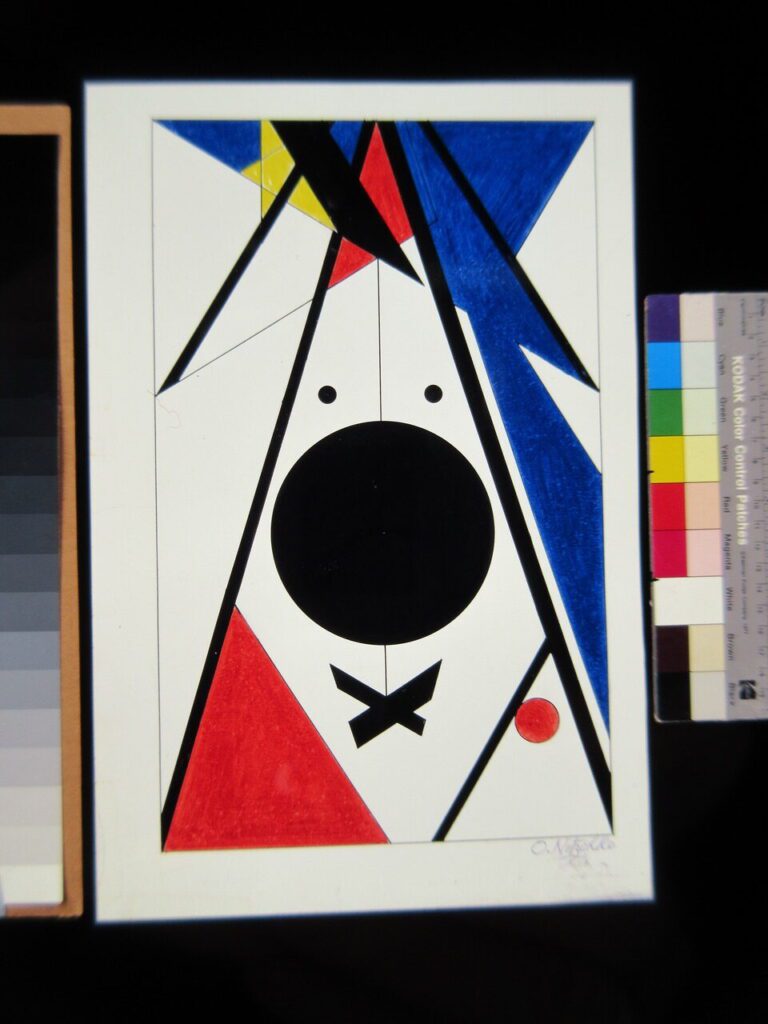

Oscar Nitzchke, Avant-garde Architect of the Modernity 1900 – 1991

Lea Lee

Annie Markovich

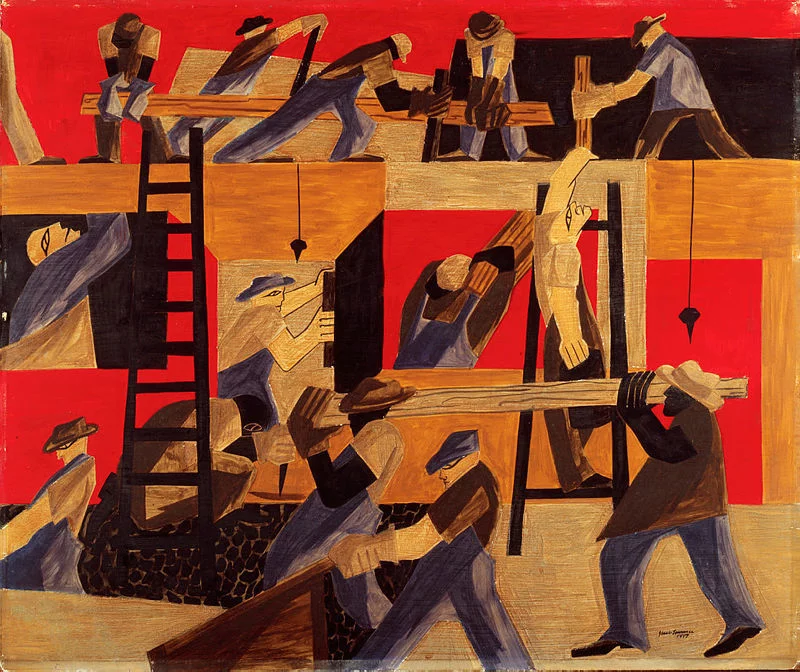

Cross Cultural Histories of the Black Experience, 1920-1940

Lanita K. Brooks Colbert

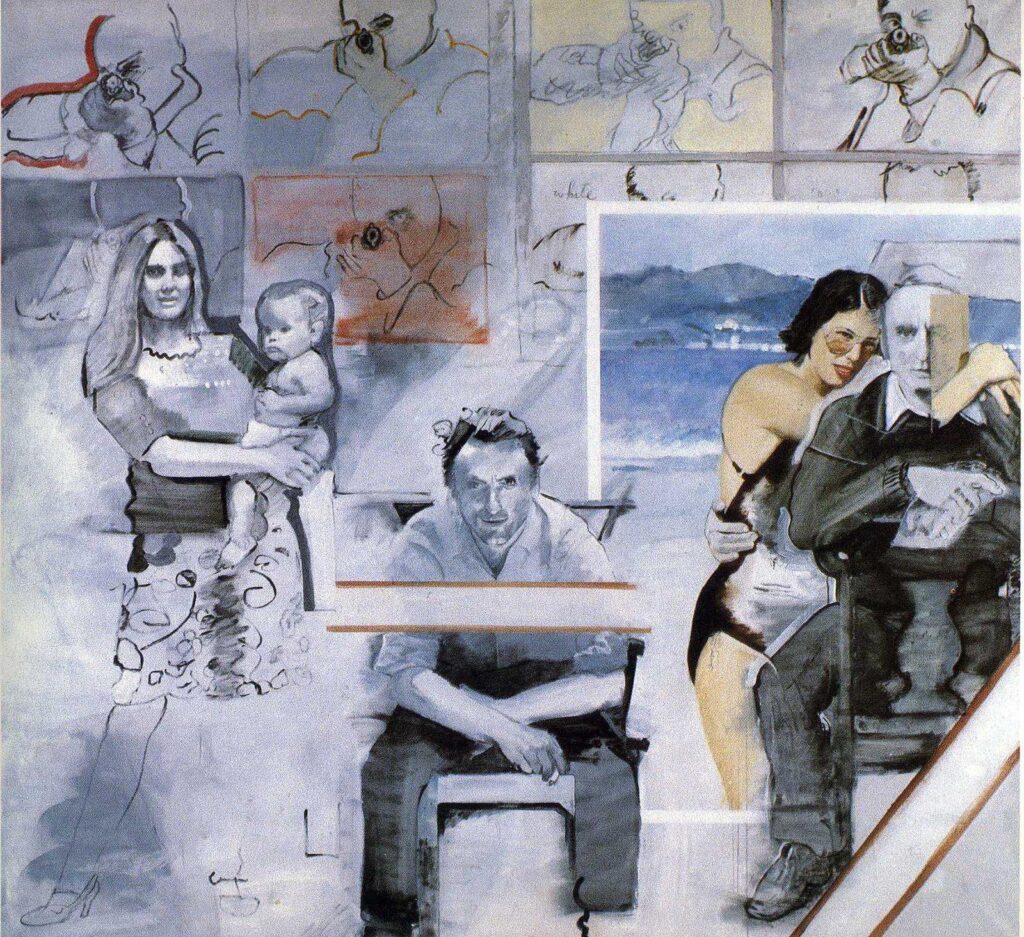

Larry Rivers: Bad Boy of the Art World

Rina Oh Amen

Mary Fletcher

May-June 2024 (Vol. 38, No. 5)

March-April 2024 (Vol. 38, No. 4)

PERU

An American in Lima: A Meditation on a Divided Hemisphere Jorge Miguel Benitez

LONDON

Entangled Pasts 1768 – Now David Goldenberg

ITALY

El Greco: His Own Peculiar Style Liviana Martin

Speakeasy Miklos Legrady

AFRICA

Front Seat to a Revolution Valerie Kabov

LONDON

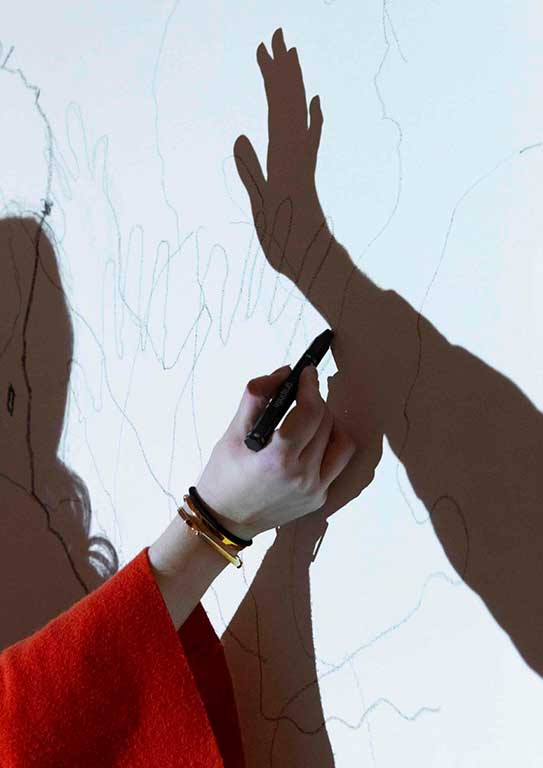

When Forms come Alive Nancy Nesvet

BOOK REVIEW:

Looking at Picasso Mary Fletcher

Jan-Feb 2024 (Vol. 38, No. 3)

The Rossettis Delaware Art Museum

Women in Revolt: Art & Activism in the UK 1974-1990 Nancy Nesvet

BOOK REVIEW:

The Presence of Death Frances Oliver

Where Has All The Protest Music Gone? Jorge M Benitez

A Painter Looks at Philip Guston Now Don Kimes

NEW YORK

Its Pablo-matic According to Hannah Gadsby Elizabeth Ashe

Speakeasy Daniel Benshana

Hiroshi Sugimoto at the Hayward Nancy Nesvet

The Mother and the Weaver Nancy Nesvet

The Native Camera Liviana Martin

Elizabeth Ashe

Nov-Dec 2023 (Vol. 38, No. 2)

LONDON

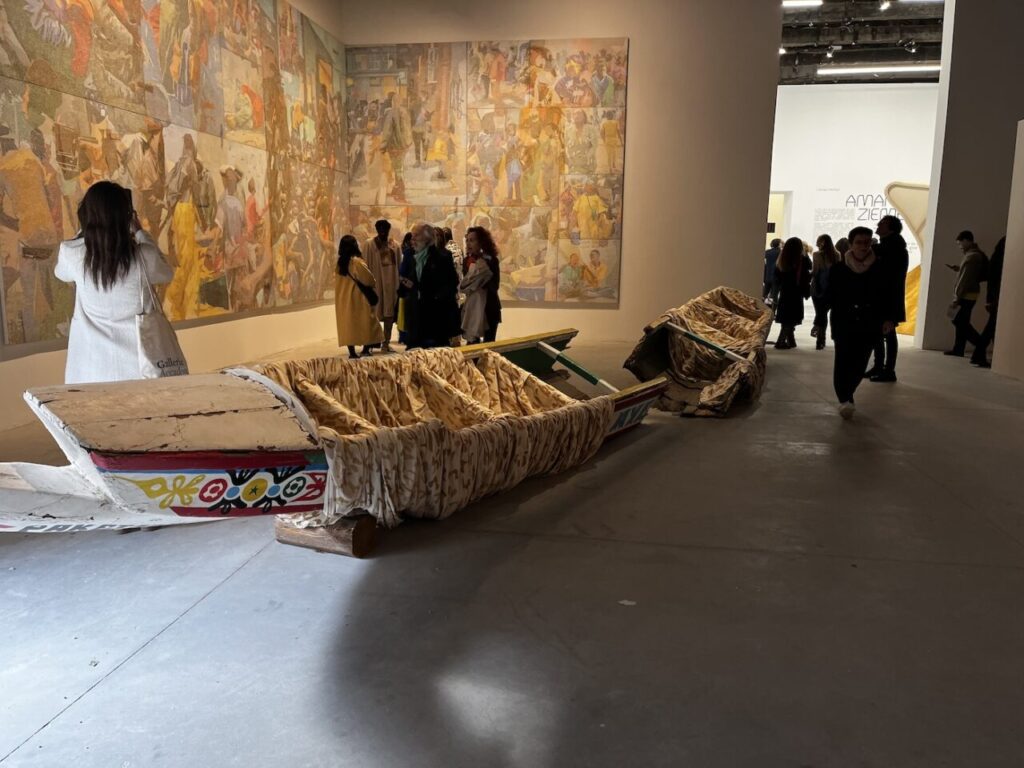

Frieze Week And Frieze Art Fair, David Goldenberg

MILAN

Robert Doisneau , Graziella Colombo

BOOK REVIEW:

Sept-Oct 2023 (Vol. 37, No. 8)

Speakeasy – The inexorable rise of the art market, Scott Reyburn

Learning From The Masters. Bradley Stevens

For Bradley Stevens, copying the masters at museums is an ongoing education.

Cuba as Realised in Art, Lanita K. Brooks Colbert

Free art education, murals everywhere, and a national museum: Lanita K Brooks Colbert reviews Cuba’s art scene while on a cultural mission.

The Only Thing that’s the End of the World is the End of the

World Elizabeth Ashe

Elizabeth Ashe sees The Only Thing that’s the End of the World is The End of the World” at the Payne Gallery at Moravian University, an installation challenging viewer’s perception of space and place.

Rodney and the Imagination Nancy Nesvet

Artist Rodney Zelenka draws on migrants’ travels, surrealistically using birds and spiders to see something new.

Back to the Future (Art), Stephen Westfall

Stephens Westfall on what happens when the artist leaves the classroom for the unknown.

The Geopolitics of Biennials: Simina Neagu Interviews David Goldenberg

David Goldenberg speaks about art, geopolitics and his new take on the Biennale in an interview with Simina Neagu.

The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh (Book Review) , Frances Oliver

Why have critics failed to engage with our most important current issues: climate change and exhaustion of the earth? Francis Oliver reviews “The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable” by Amitav Ghosh.

The Once and Future DIY Network Mark Bloch

Mark Bloch reviews the decades old practice of making mail art, and his own mail art work.

Here’s looking at You, Casablanca Mary Fletcher

Mary Fletcher reviews the Casablanca school exhibition at the Tate Cornwall, casting new light on a little know but important phenomenon in the 1960’s art world.

Ex Statu Pupillari: Against Guardians Sam Vangheluwe

Sam Vangheluwe writes of the value of getting lost: in a place, a work of art, or anywhere, and the joys of discovering for ourselves what we see and where we go.