Five years in, The Whitney has become thoroughly at home in its spacious new digs and primo downtown locale. This is the second substantial collection re-installation since the new building’s inaugural extravaganza. This rotation and attention to expanded contexts for a few renowned works that have remained on view in shifted juxtapositions is notable. The salon-style hanging in a dark blue gallery at the start (facing the seventh floor elevators) is

Five years in, The Whitney has become thoroughly at home in its spacious new digs and primo downtown locale. This is the second substantial collection re-installation since the new building’s inaugural extravaganza. This rotation and attention to expanded contexts for a few renowned works that have remained on view in shifted juxtapositions is notable. The salon-style hanging in a dark blue gallery at the start (facing the seventh floor elevators) is  effective in setting a range of mood, scale, and subjects popular in painting in Depression Era America. Ironically, an elite few were concurrently establishing galleries and museums, like the Guggenheims, the Rockefellers, and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, whose Whitney Museum of American Art opened in 1931 (in Greenwich Village). GVW was a committed supporter and promoter of living artists, not to mention, an artist herself aware that her career in that regard was inhibited by conflicts of interest with her broader mission. (None of her several sculptures in the collection appear in this show; photographic images of her in the early building do). Her interest in contemporary American artists contrasted, for the most part, with her patron-of-the-arts peers and left a strong artistic record of the years between the wars on the American scene. Nicely foregoing disruptive wall labels, placards are available for reference. Renowned Regionalists like George Bellows and Thomas Hart Benton are immediately recognizable, partly due to their early and close identification with the Whitney. There were several women artists in this arrangement and elsewhere throughout that I was unfamiliar with previously, including Madeline Shiff (aka Wiltz), whose lively portrait of her artist-husband painting a landscape in a windowless studio (Wiltz at Work, 1932) perhaps both reinforces and goes towards filling the lacunae regarding her own art practice.Overall, real estate was rightly apportioned according to the museum’s holdings, starring Edward Hopper. One of the great “poignant clown” depictions of many in modernist painting appears in his early Soir Bleu (1914), a post-Impressionist-like Parisian pub scene and last European nod for the artist. Across the room and several decades the sublimely distilled New York air of Early Sunday Morning (1930) beckons. Nearby are works by Georgia O’Keeffe, whose approach to the visual world, via the results, are diametrically opposed. Sharing some stylistic aspects which each and much more, a number of panels from Jacob Lawrence’s War Series (c. 1946-47) shows off his truly experimental, washy palette and repetitious, rhythmic form, yet forcefully conveying its humanistic, topical content. Alexander Calder’s low-tech kinetic Circus (1926-1931) is featured in a documentational film (1961; transferred to bright video) in which the artist activates his ensemble. That is, he cranks, blows, twists, and otherwise manipulates his miniaturist mixed media props, characters and animals into action ingeniously. If art is play for adults (as some psychoanalytical theories suggest) Calder was deep in and highly convincing. Postscript: great art can be fashioned from the sparest scraps of detritus.

effective in setting a range of mood, scale, and subjects popular in painting in Depression Era America. Ironically, an elite few were concurrently establishing galleries and museums, like the Guggenheims, the Rockefellers, and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, whose Whitney Museum of American Art opened in 1931 (in Greenwich Village). GVW was a committed supporter and promoter of living artists, not to mention, an artist herself aware that her career in that regard was inhibited by conflicts of interest with her broader mission. (None of her several sculptures in the collection appear in this show; photographic images of her in the early building do). Her interest in contemporary American artists contrasted, for the most part, with her patron-of-the-arts peers and left a strong artistic record of the years between the wars on the American scene. Nicely foregoing disruptive wall labels, placards are available for reference. Renowned Regionalists like George Bellows and Thomas Hart Benton are immediately recognizable, partly due to their early and close identification with the Whitney. There were several women artists in this arrangement and elsewhere throughout that I was unfamiliar with previously, including Madeline Shiff (aka Wiltz), whose lively portrait of her artist-husband painting a landscape in a windowless studio (Wiltz at Work, 1932) perhaps both reinforces and goes towards filling the lacunae regarding her own art practice.Overall, real estate was rightly apportioned according to the museum’s holdings, starring Edward Hopper. One of the great “poignant clown” depictions of many in modernist painting appears in his early Soir Bleu (1914), a post-Impressionist-like Parisian pub scene and last European nod for the artist. Across the room and several decades the sublimely distilled New York air of Early Sunday Morning (1930) beckons. Nearby are works by Georgia O’Keeffe, whose approach to the visual world, via the results, are diametrically opposed. Sharing some stylistic aspects which each and much more, a number of panels from Jacob Lawrence’s War Series (c. 1946-47) shows off his truly experimental, washy palette and repetitious, rhythmic form, yet forcefully conveying its humanistic, topical content. Alexander Calder’s low-tech kinetic Circus (1926-1931) is featured in a documentational film (1961; transferred to bright video) in which the artist activates his ensemble. That is, he cranks, blows, twists, and otherwise manipulates his miniaturist mixed media props, characters and animals into action ingeniously. If art is play for adults (as some psychoanalytical theories suggest) Calder was deep in and highly convincing. Postscript: great art can be fashioned from the sparest scraps of detritus.

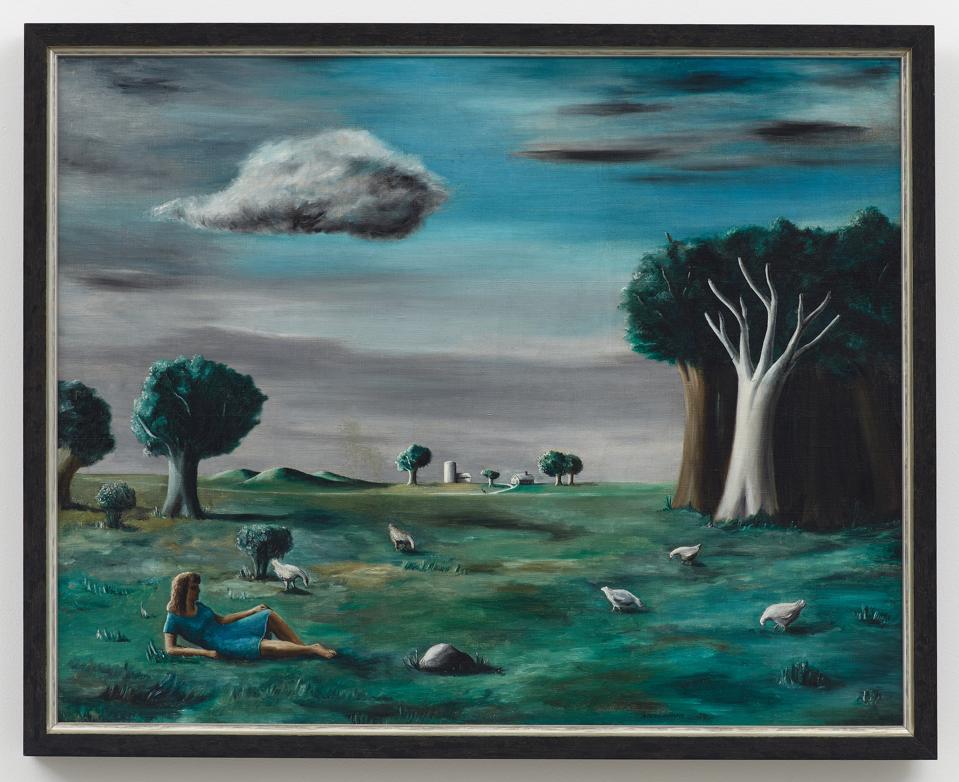

Other pre-WWII works are grouped in relatively familiar ways, for example “Machine Age” aesthetics, exemplified by the cubistic architectural paintings of Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth and Art Deco sculpture by John Storrs; and Surrealist-tinged work, which, in the United States, elided with stylistic and thematic elements of Social Realism and Regionalism, whether or not with conscious intent. A remarkable contribution here in view of later video art, is an animated film of whimsy ghost-like shapes by Mary Ellen Bute (Spook Sport, 1939). Stand outs on their own include a quirky ode to the end of WWI that adds fabric folds to Lady Liberty by painter Florine Stettheimer, later affiliated with Surrealism, and the quietly uplifting terracotta-as-bronze Head (1947) by Elizabeth Catlett, whose oeuvre bridged the late Harlem Renaissance and Black Arts Movement.

The Abstract Expressionist section is energized by a boldly splotched Ed Clark canvas and a crusty, monumental relief painting by Jay DeFeo. Dominating the postwar spread overall is Tom Wesselmann’s ginormous Still Life Number 36 (1964), from his loose kitchen-counter collage-paintings series, which could not better anticipate the Photoshop-based paintings of Jeff Koons and other “commodities” artists of the digital age. Warhol’s silver-screened Elvis Two Times (1963), however, still packs the strongest Pop punch despite, or because of the artist’s continuing resonance in in so many spheres of the art world.

A more modest exhibition on another floor on color in painting of the 1960s works as a kind of addendum, first and foremost suggesting how d

ominant abstraction had become by then. Kenneth Noland’s dizzying and sprawling “post-painterly” (á la Clement Greenberg) striped abstraction at the entrance (New Day,1967) looks thoroughly triumphant. A now classic stained canvas “bunting” piece by Sam Gilliam stands out against the majority geometrically-defined color-blocked experiments that describes most works included, some differentiated just slightly from others among several different artists. And some representational artists, it is proposed, nonetheless focused primarily on color in at least some work of this period, as in examples by Alex Katz, Bob Thompson, Kay Walkingstick, and Emma Amos. A thoughtful but not too didactic display that gives good ground for a venture, or return to, the 2019 Biennial also on view through September 22.

Jody B. Cutler-Bittner

volume 34 no 1 September – October 2019 pp 22-23

“Spilling Over: Painting Color in the 1960s, March 29 – August 28, 2019. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York