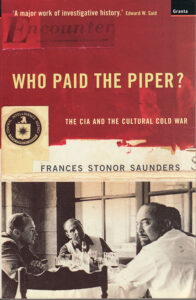

With elements of a new Cold War – interspersed with irregular hot wars and even a re-run of the medieval Crusades against rampant Islam in the guise of ISIS occupying half Syria and a third of Iraq in just one year, and a rejuvenated Al Quaeda in the form of Jabhat Al Nusra very much a reality, it is a good time to reconsider the relationships between power, society and culture. This thought was triggered by a review of a this book which examines essentially the cultural Cold War – 1946, starting with Churchill’s famous Fulton, Missouri speech proclaiming the Iron Curtain between the Soviet Union and the West and ending with the end of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European Bloc in 1991- as opposed to the political, military and socio-economic aspects that dominated headlines and general consciousness over that period. It should never be forgotten however that the Cold War also triggered conflicts in which multi-million civilians died (3 million in Korea and 4 million in Vietnam both wars in which overwhelmingly the killing was done by US B-29 & B-52 bombers, a point highlighted by Harold Pinter in his Nobel Prize in Literature acceptance address in 2005.)

With elements of a new Cold War – interspersed with irregular hot wars and even a re-run of the medieval Crusades against rampant Islam in the guise of ISIS occupying half Syria and a third of Iraq in just one year, and a rejuvenated Al Quaeda in the form of Jabhat Al Nusra very much a reality, it is a good time to reconsider the relationships between power, society and culture. This thought was triggered by a review of a this book which examines essentially the cultural Cold War – 1946, starting with Churchill’s famous Fulton, Missouri speech proclaiming the Iron Curtain between the Soviet Union and the West and ending with the end of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European Bloc in 1991- as opposed to the political, military and socio-economic aspects that dominated headlines and general consciousness over that period. It should never be forgotten however that the Cold War also triggered conflicts in which multi-million civilians died (3 million in Korea and 4 million in Vietnam both wars in which overwhelmingly the killing was done by US B-29 & B-52 bombers, a point highlighted by Harold Pinter in his Nobel Prize in Literature acceptance address in 2005.)

Saunders’ focusses on CIA activity – originated in the National Security Act of 1947 and the CIA Act of 1949 – both open and covert. It should be born in mind that the CIA is involved mainly in overseas activity, like its UK equivalent MI6 as opposed to domestic surveillance carried on by the FBI, like the UK’s MI5 and to some extent Special Branch. The covert activities involving cultural and psychological warfare were carried out through a multiplicity of complex networks focussed on the multi-faceted Congress for Cultural Freedom.

The CCF was funded and controlled by the CIA but also fed funds through various philanthropic arts organizations such as the Carnegie, Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, institutions all dedicated to directly or indirectly promoting the ‘American Way’, as propounded by President Truman in his Truman Doctrine speech of 1948 after his unexpected election triumph over Dewey. It was of course the CIA which over the next 40 years covertly sponsored or engineered the overthrow of popularly elected democratic regimes in Central and South America and also in Indonesia in 1965 resulting in a massacre of 1 million so-called Communists by the new pro-American military dictatorship of General Suharto.

Directly or indirectly the CIA manipulated financial aid and controlled contributors to all media within the ambit of the CCF so as to align Western Europe in particular with the Americans and counter Soviet propaganda and cultural influences on an area which was itself massively financed by Marshall Aid. This was when, in the early stages at least, Communist parties were particularly strong in France and Italy. Greece had a long civil war (1944-48) and Germany was divided between East and West.

Even Britain which had run up $31 BN in lend-lease debt to the US had a Labour government which had won a landslide victory in 1945 and indulged in significant nationalisation of private industry. So the two superpowers the USSR and the USA slugged it out during the Cold War (with the possibility of nuclear Armageddon always in the background and nearly implemented in the Cuba Crisis of 1962), each attempting to impose their own nasty brand of un-freedom masquerading as the exact opposite in every area they could wield their influence.

It seems the CIA was responsible for backing Abstract Expressionist art (Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman followed by the American equivalent of Piet Mondrian Mark Rothko, who is on photographic record as having visited Cornwall when St Ives was at its peak, against the perceived Soviet art form of so-called Socialist Realism. Ironically the early Cold War also saw an unprecedented consumer boom (1955-70) and not coincidentally – Pop Art with Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell Soup Can paintings (all different!) creating perfect reproductions of iconic branded products and Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings did takes on teenage comic strip romances complete with conversational bubbles.

Frances Saunders touches only marginally on the main UK area of CIA-funded CCF activity which was centred on the highly influential journal Encounter. This magazine was effectively CIA-funded from the start but astonishingly the co-Editor from 1954-1966, Stephen Spender discloses in his Journals 1939-83 that it was only in 1976 that he found out the CIA-connection with the CCF and therefore indirectly Encounter. He and his successor Frank Kermode then immediately severed all connection with Encounter, having been CIA dupes for its Anti-Communist crusade for the hottest part of the first stage of the Cold War. There is incidentally no mention of this CIA connection in the official biography of Stephen Spender by Professor John Sutherland (Penguin Books 2005).

The extent of CIA covert activities is astonishing. As early as 1960, the year President Eisenhower attacked the predominance of ‘the military-industrial complex’ in America in effect ‘The Power Elite’ analysed by the sociologist C. Wright Mills in his seminal – and it still prevails right across American society and institutions – the CIA had secret files on 430,000 individuals and organizations. In the earlier post-war period this was paralleled by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) with its mass investigations of Hollywood and other US cultural and artistic areas generally to the detriment of the people concerned. Under the Kennedy brothers (President JFK and Attorney General Robert, assassinated respectively in 1963 and 1968) the CIA launched 163 covert campaigns in 3 years. From 1954-74 the CIA’s OISP trained 771,217 secret police officers and secret agents in 13 overseas territories. The extent of all these activities was revealed by the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 2007 and of course by the recent whistle-blowing activities of the Guardian and Mr Snowdon, currently holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy in London.

The 9/11 Twin Towers terrorist attack in 2001 launched additional security organizations and funding, notably the Department of Homeland Security (budget $15BN ) now featured in its own TV series starring Daniel Craig alias James Bond. The UK equivalent MIG tripled its numbers from 1,000 to 3,000 immediately after the 7/7 attack in London (2005).

Unlike the US counterparts there is no evidence of MI5 or MI6 having either the inclination or the resources to support any institution in the UK like the CCF or to try to indirectly promote the British Way of Life. Instead, there is the interesting issue of funding for the arts in the UK through monolithic institutions such as the Arts Council and the Tate and their equivalents of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. This is discussed by the current chairman of the Arts Council in a recent paper. The message is loud and clear that official sponsorship and funding is on the wane (down 37% in 10 years) and joint projects and new types of public-private partnership will have to be found. The example given is a new Arts Impact Fund with a princely backing of £7m, coming from a mixture of the commercial sector, charities and the public purse. The outlay will involve repayable loans up to £600,000 not a penny in grants. The one positive aspect is that there will be for more funding for community arts and areas outside London with the capital city’s slice of the cake falling from 30% to 25%.

It has been remarked that 9/11 has produced no significant artistic response although an anti-Iraq War installation won the Turner Prize in 2005 and the Occupy Movement (in response to public outrage at Banker’s Bonuses and over-the-top executive remuneration which appears to correlate with business non-performance or even outright failure), looks like delivering something of import on both the literary and artistic fronts. Certainly we live in an age of high-tech exponential change co-existing with equally exponential polarisation between the haves and the have-nots.

A recent figure was that the richest 100 people in the world have more wealth than the bottom 50% of the world’s population. The USA has 20% of global GDP and 4.4% of the world’s population. This is the long-term outcome of the kind of activities described in some detail in the book and review and the source-books I have used for these reflections.

As a final thought I would like to cite two quotations from art critics that recently caught my eye. One is from Donald Kuspit, art professor and a contributor of in my view the best feature in “The Essential NAE” anthology:

“Aesthetic experience transforms alienation into freedom and adversariness into criticality.”

The other is from a leading work on modern art, ‘Art Since 1960’ by Michael Archer((Thames & Hudson 2002):

“Art is a continuing reflective encounter with the world in which the work, far from being the end point of that process, acts as an initiator of and focus for the subsequent investigation of meaning.”

Sources: Stephen Spender Journals 1939-1983(Faber 1985)

Chris Harman : A People’s History of the World

Oliver Stone & Peter Kuznick: The Untold History of the United States(Ebury Press 2012)

Norman Stone: The Atlantic & Its Enemies(A History of the Cold War) (Basic Books 2010.)

Roland Gurney is a Cambridge History Scholar and is a law graduate with 32 years experience as a financial adviser. He has a special interest in world literature and world history and is an award-winning poet.

Volume 30 number 1, August / September 2015 pp 38-40