Charlotte Moorman was an artist of many guises: champion of the cello, muse of the avant-garde, a master networker of “New Music” and an early practitioner of 1960s mixed media “Happenings”.

This beautiful and utterly charming, woman, moved from a traditional upbringing in Little Rock, Arkansas to classical training at Juilliard and, eventually, became a leading performance artist of New York’s avant-garde scene for more than two decades. Critics have long debated whether an artist’s biography should be independent of his or her work. But in Moorman’s case, biography feels imperative for Charlotte was her art.

This misunderstood figure, known for such transgressive performances as “TV Cello” and “TV Bra”, is now receiving a long-overdue re-examination of her artistic career in a comprehensive exhibition, “A Feast of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde, 1960s to 1980s” at the Block Museum in Evanston.

Upon entering the main gallery, one is confronted with a kaleidoscope of sound. One hears, and sees, excerpts of

Moorman’s performances with non-traditional instruments kazoo and metal, intermixed with the classical pull of her cello. Moorman’s warm voice, speaking about her performances, is woven through the fabric of sound.

As with most “Happenings” documentation, the exhibition presents artifacts from her performances – her wardrobe and avant-garde cellos, photos and memorabilia from the fifteen Avant-Garde Festivals she organized in New York City. Photos show a lovely woman performing her musical pieces with dignity. Her face betrays no trace of any awareness of acting ridiculously. All the documentation is drawn from her archive that is housed at Northwestern’s Library.

The Sixties and Seventies were crucial decades when artists challenged the contradictions of art’s canon and when art historians began investigating radical approaches to art. The avant-garde has long been classified as meeting the need for a new visual language. Charlotte, “A Feast of Astonishments” argues, was a translator, transmitter, and the “Joan of Arc of New Music” as composer Edgard Varese called her.

Moorman’s collaborations with such noted artists as John Cage, Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono share a particular mix of tradition and nihilism. In particular, the Saint-Saens solo performance piece that Paik created for her is representative of his tendency to interrupt classical pieces with irreverent action. It required her to pause midway through the work, then jump into an oil drum filled with water, emerge and resume playing.

I found it striking that Moorman would wear classic concert dresses when the composer or notes did not require otherwise, and insisted that the cellos she played be functional. Such an attitude attested to her loyalty to her medium, even as she broke its rules. “I don’t feel that I’m destroying any tradition,” Moorman once said. “I feel that I’m creating something new.”

In another performance, ‘One for Violin’, Moorman gracefully raises a violin over her head and smashes the instrument over a table, predating The Who’s Pete Townsend by more than 20 years. The splintered remainders are on display in a glass box and completely encapsulate Moorman’s esthetic: respectful of the instrument but disruptive of its structure.

After a multi-instrumental performance on Mike Douglas’ talk show, Moorman was asked “Are you serious about your music?”, to which she replied evenly, “Oh, very definitely, but it’s not music. It’s a mixture: theater, environment, cooking, lighting, everything is important. The cello sounds are only one thing.”

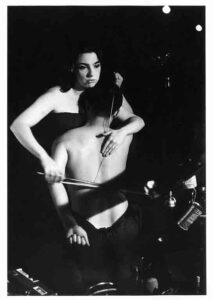

Viewing the precious artifacts that clothed Moorman’s body, such as her electric bikini or her TV bra, I sought a deeper conversation with Moorman’s body which was especially exemplified in her topless performances. While performing Paik’s infamous “Opera Sextronique,” Moorman was arrested by New York City police and charged with lewdness and indecent exposure. Moorman famously countered that she needed to be topless because that’s what the piece called for.

Moorman’s body was integral to her art. Her body was her instrument, whether it was her Sky Kiss, where she was lifted into the air in a balloon and floated over the town while playing her cello or Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece where viewers could cut away at Moorman’s dress while she sat primly on a low stage. In the end, Moorman would submit to her body, dying in 1991 after a long battle with breast cancer.

The Block’s exhibition is appealing in that it fits in with other post-modern revisions of art history wherein women are finally given their due for all that they put into their art. For this revision in particular, with all artifacts of Moorman’s art on display, her significance speaks for itself.

The Block asks visitors to take Moorman as seriously as she took herself, that she did not fall back into irony. Moorman was so fluid in these pieces, constantly opening herself up as a performer. Throughout, she was always herself, a classically-trained musician carving out genuinely new notes for both herself and the avant-garde.

Rachael Schwabe

Rachael Schwabe is a fourth year art history student at Loyola University Chicago. Her academic focus is on picturing women and gender in art and literature.

“A Feast of Astonishments” The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art January 16th – July 17, 2016.

Free Admission. Open times: 10am-8pm on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday 10am-5pm Tuesday, Saturday and Sunday.

For more information about the Block Museum and its events visit Block Museum

Volume 30 number 4 March / April 2016 p 35-36