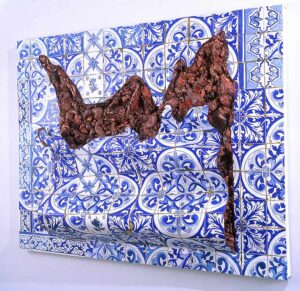

Pablo Halguera

Barroquismos: Conceptual readings of the 17th century.

Oil, foam, aluminum, wood and canvas

Photo: Lehman Maupin

Last week I was in Puebla to do research for a museum project. Puebla is very dear to my heart – a city where my mother grew up, and where I visited frequently as a child when my father travelled for business there. Many important artists and writers were born and worked in Puebla; the only official avant-garde movement in Mexico, Estridentismo, published its second manifesto there. It is not only a culinary capital but also one of the geographic areas where the Baroque in Latin America reached its most spectacular climax – in buildings like the Capilla del Rosario and Santa María Tonantzintla in Cholula.

I thus was very interested to visit, for the first time, the Museo Internacional del Barroco, which opened in 2016. The handsome building was commissioned by the state government to Japanese starchitect Toyo Ito with an official budget of 37 million dollars (although that seems highly unlikely; unofficial figures put it at a much higher cost, up to the hundreds of millions). The massive 18,000 sq. meter complex, nearing the Guggenheim Bilbao’s 24,000, undoubtedly had great aspirations.

When I and a colleague entered we were the only visitors in the entire museum. There were a dozen eagle-eyed guards around us, monitoring our every movement, as well as cleaning staff incessantly swiping the already squeaky-clean marble floors, giving the whole museum a general fragrance of Ajax Pino. With counted exceptions, the vast majority of the collection is ‘borrowed’ – mainly aggregated out of loans from other local colonial art museums and in some instances with rented works from European museums, likely (I suspect) at a great cost to Poblano taxpayers. I was told the museum had no education department, and my research did not find any evidence of education programs. The interiors resemble, more than a museum, a mall in suburban New Jersey, and the exhibitions seem as if designed by an advertising agency that specializes in designing automotive trade shows – only featuring works of Cristóbal de Villalpando. It is the first museum I have visited in my life where I felt that the art works were used as props.

The contemporary exhibitions, supposedly engaging with the baroque aesthetic, include a ceramic solo show by an artist who makes pieces such as a cookie-jar shaped Talavera ceramic bear with an erection and the bust, a singing woman with a bird atop her head.

The first piece one encounters in the museum lobby is a plaster cast copy: a monumental, 13-foot equestrian sculpture of Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia whose original one can see in Berlin. Which made me think: if one is going to go as low as to exhibit a plaster copy, why not just at least pick the best, like Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa? But the selection of an all-powerful European ruler might psychologically make sense when one learns how this museum came to be. It was commissioned by Governor Rafael Moreno Valle (who tragically died in a helicopter accident a year after the museum opened). The current government, with a leader from a different political party, have had no choice but to honor the burdensome loan contracts created by the previous administration, and they are not happy about it. Just last month at a press conference the current governor called the building ‘magical but cursed’, and added that they will turn it into a “virtual” museum given that “it costs too much to have real artworks in it” (a statement by which I assume one will be able to attend this palatial building to look at flat screens and websites). At present, the museum evokes anything baroque, it primarily is the period’s cult of extravagant festivities and displays (i.e. a lavish museum) for the pleasure of an absolute monarch (i.e.. the governor or Puebla). It’s a museum built for a single viewer who is now deceased.

Political vanity projects aside, the museum stimulated in my mind the question of how we could pursue a research project (museum or otherwise) focusing on the legacy of baroque aesthetic in contemporary art.

The interest in the Baroque in contemporary art has always been ongoing and multivaried, both in Latin America and elsewhere. The examples abound. Recently, in 2018, Luc Tuymans curated a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp that engaged with the high-drama and tenebrism of the Baroque, in particular the legacy that pertains to Flanders.

Thinking back to Latin America, in 2000 Elizabeth Armstrong and the late curator Victor Zamudio-Taylor curated the important exhibition Ultra Baroque: Aspects of Post Latin American Art, which sought to dispense with the many clichés associated with the period and feature works by artists who conceptually connected with its painting tradition (like Yishai Jusidman) or its decorative arts one (like Adriana Varejão).

I asked Armstrong to reflect back regarding that project to share the perspective they took on the baroque. I quote her response:

“When I first started talking about contemporary Latin American art with a group of scholars in the field (which is how I met Victor), it was to take a fresh look at Latin American artists working outside of the stereotypes that were commonly used at the time such as Magic Realism and the Baroque. In the 1990s, my advisors believed these two movements were constantly evoked to define – and limit – modern and contemporary Latin American art. But we were basically talking about “style” and aesthetics.

Rather than overlooking the definition of a baroque aesthetic, I think it’s fairer to say that we became much more interested in the globalizing impulses that emerged in Latin America in tandem with its colonization (during the period of the Baroque). And that hybridity is what I began to see as a strong throughline that transcended the stylistic stereotypes of the baroque used about Latin American art. Even when it involved painting, as in the case of Adriana Varejão, it had a conceptual element that referred to colonization and related cultural clashes. Revisiting the Baroque period in Latin American art led us to the way in which colonial subjects who became artists and artisans began to create new hybrid forms based on cultural cannibalism and appropriation.”

Armstrong adds: “we were responding to the way that North American and European art historians and contemporary critics relied on these stereotypes about Latin American art – which, to some extent, had become derogatory clichés. For example, some of the most prominent Latin American artists of the period were Julio Galán and Beatriz Milhazes. I have great respect for each, and their respective aesthetics were very much in evidence at this year’s Venice Biennale. Leonora Carrington comes to mind, whose work was often described as ‘baroque’ or ‘magic realist’ and which was unpopular for so long. That work and those styles are popular once again, as witnessed by the current Venice Biennale.

Going beyond Latin America and considering the present moment in art, it can still be argued that the clichés that Armstrong and Zamudio-Taylor were questioning still persist to this day: in general when we use the term baroque to define certain art projects we still think of it in fairly formal narrow terms, mostly referring to elaborate, over-the-top, or heavily ornamented works. But the aesthetic of the Baroque is generally misunderstood and in reality it is much more complex; in many ways it laid the foundation for important aspects of modern art.

It has often been observed that the mathematical/symmetrical approach with a limited set of elements and formulas in composition that characterizes 20th century minimalist music can find its precursor in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the late Baroque period. Bach alone is a fascinating subject to explore as a topic for contemporary art. One of Bach’s many fans was no other than Sol LeWitt, who often listened to Bach in his studio (he had a library of about 4,000 recordings). In a recent exhibition drawing of this relationship at the Williams College of Art, the curator writes: ‘Like Bach, LeWitt found extraordinary richness in systematic formal logic, developing complex structures out of the simplest elements such as a two-by-two grid with lines in four directions.’

Following on Bach’s underlying compositional principles and approaches, we might find foundational ideas for the art we make today: for example, when one considers Bach’s breathtaking Crab Canon from 1747 (a vignette palindromic composition where the second voice is a perfectly inverted version of the first voice and they mirror each other as in a perfectly shaped Möbius strip) how can one not see this as an artistic precedent for conceptual art?

It might also be interesting to consider that 300 years before conceptualism emerged, a Spanish literary movement named conceptismo (primarily represented by Francisco de Quevedo) competed with a more specific and even more erudite variant of it, ‘culteranismo’, whose main representative was Luis de Góngora. Baltazar Gracián defined conceptismo as ‘an act of understanding that expresses the correspondence between objects’.

Are the terms conceptualism and conceptism merely a coincidence? The immediate answer might be yes, but when one considers Duchampian visual puns, he is operating with the meaning of words and with the ingenious reimagining between them, for instance Fresh Widow, which is a variation of an ellipsis – a devise often used by Quevedo and others of the period.

Speaking of Duchamp, French wi(n)dows and other home furnishings, I probably would have never thought about possible connections between conceptual art and the 17th century, had I not seen an intriguing image in the last page of Alexander Roob’s Alchemy and Mysticism (published by Taschen in 1996) a book that has been popular over decades as a visual reference of Hermetic imagery for artists worldwide. Roob chose to include Duchamp’s Door: 11, rue Larrey – seemingly not so much of an argument but a provocation, one to incite us to think about the hermetic elements of surrealism (thinking back of Gracián’s definition of the correspondence between objects, it might not be hard to think also of Comte de Lautreamont’s almost parallel definition of surrealism as “the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on an operating table.”