Giacomo Tagliani

Is it still possible to say something new and thought-provoking about Federico Fellini? Some scholars have recently addressed this challenge by proposing new interpretations of the Italian director’s work, looking at different aspects – in some cases, previously neglected – of his heterogeneous and vast universe.

Hava Aldouby is one of those who have undertaken and succeeded in this task; her book explores the relationship between cinema and painting in the so-called middle period of Fellini’s career, roughly between 1965 and 1980,  which is distinguished by a marked painterly slant. These works and their particular intermedial characterization, Aldouby argues, questions on the one hand the classical periodization of Fellini’s entire oeuvre, and, on the other hand, a normative approach – by both theoreticians and directors – to the cinema/painting nexus.

which is distinguished by a marked painterly slant. These works and their particular intermedial characterization, Aldouby argues, questions on the one hand the classical periodization of Fellini’s entire oeuvre, and, on the other hand, a normative approach – by both theoreticians and directors – to the cinema/painting nexus.

The book opens with a dense introduction devoted to framing the theoretical and methodological ground and to pointing out the polemical targets of the inquiry. From the very beginning, the author states the inadequacy of contemporary theory in explaining ‘Fellini’s unique mode of transmedialization’, concealed by the reputation as an untaught, child genius, and a lover of popular comic strips that he himself fostered during his entire life. On the contrary, as his private library proves, he was well aware of the cultural and intellectual trends in those years, in particular French structuralist and post-structuralist contexts: the rich intertextual layering of his films is evidence of his closeness to such theoretical issues.

Combining a post-structuralist foreground (Barthes, Kristeva) with a phenomenological approach (Merleau-Ponty, Sobchack), Aldouby proposes an idea of reading between the dialogue, which is almost political, blurring the limits between expressive forms and opening interpretation to of ‘raw meaning’ referenced by the concept of sémiotique, ‘a non-verbal mode of communication postulated by Julia Kristeva as articulating instinctual drives and primal sensations’. This conclusion leads to the third main axis (after cinema and painting) of the inquiry, that is, the role played by Jungian literature’s rich visual imagery in inducing Fellini to consider pictures as an effective mode of communication, deeply rooted in the human being’s unconscious, able to disclose the primordial structure of encounter with the world.

In Fellini’s middle period, painting seems to discharge an anti-authoritarian function, according to his emphasis on plurality and complexity as forms of resistance, as well as to assume ‘the role of origin, or core of realness whence the experience of meanings originates’, preserving a balanced tension between postmodernist issues and a romantic-like global project.

The four chapters into which the book is divided cover four different films, showing from time to time a specific aspect of this relationship. The first chapter is devoted to Giulietta Degli Spiriti (1965), in which, for the first time in Fellini’s work, ‘a new visual idiom emerges, revealing a nascent reliance on painting as potent catalyst of meaning, or rather of non-verbal experience’. Through a sophisticated film philology, Aldouby untangles the symbolist, inter-textual plot that infuses the dialogue, convincingly showing the connections between the embedded or concealed specific art-historical quotations and the anti-fascist discourse developed by narration.![]()

In chapter two, dedicated to Toby Dammit (1968), Fellini’s ‘inter-textual fabric’ moves a step further. Here the reading between the dialogue dimension primarily serves to shape a declaration of poetics encompassing both the work of the Italian director and a broad global cultural dimension. Two converging lines emerge from the film: on the one hand, the motif of the ‘butchered meat,’ which creates a resonance between Rembrandt and Francis Bacon; on the other hand, the ‘young girl’s diabolical sneer,’ which traces an axis connecting Velazquez, Picasso and Bacon again. In both cases, the comparison with Pasolini’s work of the same period effectively shows the two different approaches to the cinema/painting nexus.

The third chapter – perhaps the least convincing of the entire book – is devoted to Fellini Satyricon (1969). The grotesque tonality here assigned to Roman antiquity serves more as a critique of the ideal of Romanità pursued during the fascist period than as a reflection about late 1960s society. Once again, the analysis of the art-historical inter-text contributes to support this reading. Unfortunately, the dense plot created by the several and heterogeneous hidden quotations, which goes from Byzantine art to Klimt, from Bruegel to Picasso and Clerici, seems not to be reconstructed in a sufficiently organic scheme to allow an interpretation not limited to a superficial critique of a postmodernist aesthetics.

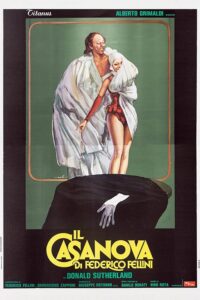

Il Casanova di Federico Fellini (1976) concludes the journey through Fellini’s middle period. Aldouby’s analysis casts a new light on the film, introducing an original interpretation that reconnects the subject to the reality, thus contrasting with the postmodernist hero inhabiting a world that has become image conscious. Even though at first glance the quotations from De Chirico seem to pursue this very direction, the interpolations with Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead and Clerici’s Latitude Böcklin are the primary tool through which cinema succeeds in restating its ‘deep and indissoluble link with the romantic’.

In her book, Aldouby proves the effectiveness of a close textual analysis of cultural objects, an essential means to chart new territories even where nothing new looked possible; Fellini’s work well represents such a case. In spite of this, a few suggestions could be proposed, mainly concerning Mitchell’s notion of ‘ekphrastic fear,’ ascribed to those directors classically involved in a ‘painted cinema,’ such as Pasolini, Godard, Greenaway. Indeed, the alleged superiority of cinema over painting, according to Frederic Jameson’s hypothesis which Aldouby refers to, that their films would state, becomes debatable. Furthermore, the opposition between a ‘stiff structuralism’ and a revolutionary poststructuralism may have seemed sound reasoning in the late 1960s, but it may have less legitimacy nowadays, at least after the works of the scholars of the so called ‘school of Paris,’ gathered around the Center of Research on the Arts and the Language at the EHESS during the 1980s. These scholars have, in addition, extensively worked on an ‘analytical iconology’ (Damisch, Marin Arasse), combining psychoanalytical instances and textual analysis, which could be of some interest for Aldouby’s approach.

In her book, Aldouby proves the effectiveness of a close textual analysis of cultural objects, an essential means to chart new territories even where nothing new looked possible; Fellini’s work well represents such a case. In spite of this, a few suggestions could be proposed, mainly concerning Mitchell’s notion of ‘ekphrastic fear,’ ascribed to those directors classically involved in a ‘painted cinema,’ such as Pasolini, Godard, Greenaway. Indeed, the alleged superiority of cinema over painting, according to Frederic Jameson’s hypothesis which Aldouby refers to, that their films would state, becomes debatable. Furthermore, the opposition between a ‘stiff structuralism’ and a revolutionary poststructuralism may have seemed sound reasoning in the late 1960s, but it may have less legitimacy nowadays, at least after the works of the scholars of the so called ‘school of Paris,’ gathered around the Center of Research on the Arts and the Language at the EHESS during the 1980s. These scholars have, in addition, extensively worked on an ‘analytical iconology’ (Damisch, Marin Arasse), combining psychoanalytical instances and textual analysis, which could be of some interest for Aldouby’s approach.

In conclusion, through this interdisciplinary methodological framework and thanks to the clarity of her discourse, Aldouby’s work contributes to the revitalization of the classical field of inquiry about cinema and painting, addressing both scholars in the broad domain of visual studies, and cinephiles looking for a fresh gaze on Fellini’s oeuvre. But most of all she also sketches a potential research ground for a challenging comparative analysis of one of the most important ‘couple’ in the history of cinema: Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini.

In the near future someone may well choose to fulfil this task.

Federico Fellini: Painting in Film, Painting on Film by Hava Aldouby. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013. pp. 186. 651 Annali d’italianistica. Volume 32 (2014). Italian Bookshelf Twentieth And Twenty-First Centuries: Literature.