David Goldenberg

The illegal and elaborately staged protest in support of Palestinians on the first day of the preview set the stage and conditions for what could be possible in a Biennale at this moment of historical violence, chaos and anxiety. In many respects, works in the Biennale purport to desire direct action, within the formal and conservative framework of the existing long-standing model of the Biennale, an island within increasingly expanding right-wing and new fascist governments. This act points to what the Biennale should have done, and to a possible future; artists and art institutions taking the initiative to protest against the West’s colonial expansion through colonial violence to make an example of any colony daring to stand against its Western Imperial masters. At the very least art must take a stand against this barbarism carried out in our names.

The illegal and elaborately staged protest in support of Palestinians on the first day of the preview set the stage and conditions for what could be possible in a Biennale at this moment of historical violence, chaos and anxiety. In many respects, works in the Biennale purport to desire direct action, within the formal and conservative framework of the existing long-standing model of the Biennale, an island within increasingly expanding right-wing and new fascist governments. This act points to what the Biennale should have done, and to a possible future; artists and art institutions taking the initiative to protest against the West’s colonial expansion through colonial violence to make an example of any colony daring to stand against its Western Imperial masters. At the very least art must take a stand against this barbarism carried out in our names.

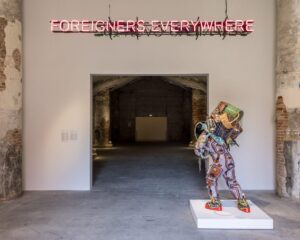

This year’s Biennale posed two fundamental problems key to the future survival of art as we know it. How do projects, purporting to use protest, resistance, decolonisation work today within a Biennial form that is an instrument of global neoliberalism, to paraphrase JJ Charlesworth? Charlesworth acknowledges that art is seriously flawed, and in a precarious position by promoting and fronting global neoliberal policies, at a time when art was supposed to be flourishing and appearing to be serious and interesting. So, what is the alternative, and a way forward, retaining this position whilst finding solutions and other models for the loss of art to new fascism and right-wing policies? My understanding, as already shown by Charlesworth, is that art has for quite some time been in the service of not just neoliberal policies, but a right-wing agenda. However, there does not exist fully formed and workable criteria and tools to register this adequately, for the obvious reason that neoliberal policies and institutions have attacked, undermined, and destroyed spaces to do this. This puts a significant burden on any audience seeking to locate value judgements to bring to the various projects, pavilions, new narratives, without recolonizing and flattening these narratives, that allege to subvert the northern hegemonic global hold on cultural power and unified global narrative? If there is no assistance or help to locate a developing criterion to be able to judge and evaluate these purported important geopolitical and cultural power shifts, how is it possible for anyone to take these important socio-political and artistic shifts seriously? Because people will assume this is just window dressing, the rhetoric of change. And, to paraphrase Claire Fontaine, from research into Deleuze and Guattari’s Minor Literature and the ‘concept of Exit’ from Agamben, locating another literature and narrative inside the Empire. “How to locate another language inside the hegemonic dominant language & narrative and neoliberal conquest of what exists today?” How to find another way of speaking and thinking within neoliberal totalitarianism and an increasingly right-wing and new fascist world? Around 2015 with the announcement of “decolonisation and post-colonialism” in the art world, it was clear that however we understood “the contemporary in art” had ended. This year’s Biennale is the clearest manifestation of the consequences of that proclamation, which l would suggest is the confirmation and solidifying of global colonisation and the neoliberal policy to incapacitate artists, theorists, philosophers’ positions to register and resist attacks against culture and art.

Therefore, it would be foolish and a fundamental error to treat this Biennale as business as usual, yet another exhibition and spectacle, with the lazy temptation to reapply existing normalized standards and judgements. That begs the question, “Where to locate the criteria as critics, theorists, artists, philosophers to evaluate new narratives, aesthetics, histories, strategies”, and is it even realistic and possible? The urgent issue here is that it has to be possible and necessary to locate this route, and I say this because it seems that current art criticism is both ill-equipped and antiquated to carry out this task, and as we can see it is not even trying to find a solution. Equally important it is necessary to ask what is possible and what can realistically be achieved within the existing regime of Western exhibition forms today. It may be tempting to overload art with complicated and demanding issues, but can art as it exists today, do this? Or is this just a trap to short-circuit such questions and important problems within neoliberal art and institutions? There is one problem that can be acknowledged, but has not been seriously examined, and l don’t think people want to understand its actual implication, namely how “The world is filtered through western art”. And how do we know that works that claim to decolonise and resist western hegemony, realise and actualise decolonization and resistance to western hegemony and that of the global north? If you look at this year’s Biennale there is no evidence of this, only the confirmation and strengthening of the position and power of the Venice Biennale itself. If this is the case then we need to ask ourselves “What is going on, what does this rhetoric amount to, and where does it lead?” This is not just a question and program isolated and specific to this occasion and art, but for everyone in the west, and to anyone who is exposed to these questions and program as it is formulated and disseminated through art, mainstream news, and global Biennales.

One strategy that the pavilions in this year’s Biennale chose to pursue, is to appear to subvert the Nation State function of the pavilions, by inviting people and cultures from different countries, or stateless peoples, from its colonies and territories, the people it has colonised, who do not have representation in the Biennale; to use their venues and in some cases, to undertake an internal analysis of the wests hegemonic cultural infrastructure.

A clear example of this is The Netherlands Pavilion “The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred” by Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise, CATPC with Hicham Khalidi and Renzo Martens. This is a highly sophisticated and important project. At first sight, it has the appearance of an exhibition of bronze sculptures, which are in fact made of chocolate. Integrated into the installation is a live link to the White Cube gallery in Congo, videos of discussions leading into the project, and clues integrated into the installation, yellow palm oil dripping down the walls like paint and wall texts, and the makers of the sculptures from the collective. This is part two of Marten’s long-term research project. The pavilion is a manifestation of Martens “White Cube project” following on from “Enjoy Poverty”. As a project, it formulates the clearest internal analysis of western capitalist and hegemonic cultural instruments’ capacity to outline and solve cultural colonialism, through Renzo Marten’s materialist embodiment of western neo-colonialism through situating an actual White Cube within the context of a Congo Plantation. Marten’s analysis of Western cultural hegemony’s starting point was the recognition that Tate & Lyle who founded Tate Britain and Modern, supports the Tate from money from its plantations in Congo and elsewhere, and that museums of Contemporary art are funded and supported by exploitation and slavery. Here, instead of articulating colonialism in the form of aesthetic commodities, in the manner of Yinka Shonibare, (also represented at the Biennale), Martens seeks to find a workable solution. However uncomfortable and disturbing it is, to the west’s colonial policies. The exhibition offers plantation workers the space to show their suffering and exploitation in their production of products sold with access to western markets, under the realization that the west has no intention of decolonising itself.

Austria invited the Russian émigré and political artist Anna Jermolaeva, to produce work for its pavilion. With an installation comprising three strands of work: the first, from her experience as an immigrant arriving in Austria from Russia, living homeless for a week on a railway station chair, using phone booths to phone home to the family she left behind. Secondly, a display of flowers representing non-violent revolutions around the world against corrupt and tyrannical governments. Thirdly, subverting cultural forms to avoid censorship and to subvert cultural signs representing the Nation-State, with installations showing smuggling Western pop music into Soviet Russia and subverting the ballet, “Swan Lake” as an image of Russia, recalling its use on Russian TV as “art to cover up change and social disturbance” whenever such social disturbance occurred in Soviet Russia. For the Biennale the artist remade “Swan Lake” with a Ukraine dancer as a “rehearsal for regime change” As used in Soviet Russia, the ballet served as a signal that change threatened to occur, whilst serving as a cover-up for attention to that threatened change

The Spanish government invited the Peruvian-Spanish artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, to Show Migrant Art Gallery. The project reveals the clearest embodiment of the Biennale’s and European States’ ambition, claims, possible delusion, and challenge of its decolonisation program. The space of the pavilion offers the opportunity to turn around the hegemony of western museums so that the peoples it has subjugated and colonized can examine and challenge that process. In this context, Migrant Museum situates the migrant into a position to analyse the mechanism of western hegemony through art, and, specifically, the history of Spanish art as a document of colonisation, to construct migrants’ own history. Gamarra uses appropriation, to sample Spanish museums and cultural forms through paintings from the colonial period during the Spanish conquest of Peru. The Installation is in two parts: Migrant Art Gallery and Migrant Garden. The first section examines the destruction of one culture by another and its depiction and organization within the gallery form. The second “subverts the dominant narrative and Colonization through offering non-hierarchical coexisting cultures and narratives as working models of decolonization.”

”Kapwani Kiwanga, a Canadian, Paris-based artist, produced a site-specific installation, titled Trinket, for the Canadian Pavilion, using materials found in Venice, “Conterie” or seed beads, employed as currency and exchange, and distributed globally. Kiwanga uses these tiny beads or units to produce intricate large-scale veils and bands, in different colours, covering the exterior, interior walls, ceiling of the venue, blurring questions of aesthetics, value, and exchange. The installation alters the venue, draws attention to its architecture, and as the artist hints, “turns the venue inside out” opening the narrow space available for art in its commodity form, while refusing to succumb to the delusion that art has content and is a form to say something beyond its commodity and neoliberal form.

Gulsun Karamustafa, representing Turkey, presents Hollow and Broken, A State of the World in the Arsenale. The installation, in a long brick-lined space, is a fine-tuned, precise analysis of signs of power and its void, the emptiness at the centre of power, symbols of western civilization and power, and the simulacra of those symbols. These are mental objects, with space and clarity between the elements to allow the audience to receive the impact of the symbols and to think very carefully about what they are seeing and thinking. The installation displays fibreglass moulds of classical columns, supported by thin skeletons of red metal, metal trollies with wheels, containing shards of broken sheets of coloured glass, candelabra constructed from broken glass, and at the very end of the space, black and white newsreels of demonstrations from multiple third world countries showing people violently beaten and suppressed by the police and army. An ensemble exposes today’s “state-of-affairs”, comprising continuous relentless trauma, state violence, wars and destruction, undermining any possibility of self-possession, calm and peace of mind. At the same time, the illusion of permanence and stability of power and civilization, artificially propped up by an invisible armature, concealing and censoring state mechanisms of violence, and the source and objective of representation and dissemination of violence to maintain the artificial construction of everyday life is revealed.

The First Nation, Scottish artist, Archie Moore’s installation Kith & Kin, joins together Aboriginal and Scottish roots to construct a work of art that is also an idea the mind registers instantly, although you don’t yet know what that idea is, because the artist is trying to carry out a difficult balancing act through his installation. The work is constructed of two elements. A monumental diagram in white chalk on black walls spread across the four walls and ceiling of a large room, surrounds a large table in the centre of the space. Stacks of partially redacted names on sheets of white paper documenting unsolved murders and deaths of Aboriginals in Australian police stations form a model of a rectilinear city. However bleak and funereal that impression is at first, and however refined the installation is, you take away nothing, this is a tomb to the dead and murdered, going back 65,000 years. However majestic and austere the work is, it is intentionally anti-spectacular, halting access to its message. The work is received as an afterglow, as a memory, spread across the installation, website, and catalogue of found photos. I was left with two thoughts. What is the correct response to this bleak shocking testimony to the crimes and violence of colonialism? The other is an observation, that the monumental genealogical diagram bursts open the pavilion space of eurocentric Imperial time into new timespace.

The British Pavilion “Listening all Night to the Rain” by Ghanian-British artist, John Akomfrah, develops a similar model and uses the pavilion as a complete unifying structure, as opposed to organizing individual parts in a space in the manner of an exhibition. The work speaks of the cultural values and production qualities that embody Britain. The work is structured into five parts, adopting the American poet Ezra Pound’s monumental Poem “The Cantos” (1915-1962). Pound spent the latter part of his life in Italy as a supporter of Mussolini. The Cantos were written in different languages, in a fluid moving structure, speaking of complexity and “sucking the World and History into itself”. Rather than linearity and mainstream narrative, echoing the tower of Babel, the overall message is obscured by a cacophony of voices. Consequently, attention shifts to the seduction and aesthetics of the display and presentation systems, and edifice of the installation – images, sound, lighting, seating, standing room, colour of the walls. The walls of videos of appropriated found stock are multiplied, cut up, buried, and submerged under water, where we can imagine that images of history are cleaned. As you walk through the installation you simultaneously catch information that is simultaneously obscured. You think you catch a glimpse, a fragmented sense of images of war, colonial violence, images of the Mau Mau and political assassinations. But above all, aspects of this lived reality; comprising sound and images and the form of platforms to present western art are filtered and reprocessed, and “What is” colonial, neoliberal, hegemonic reality broken down and reconstructed. The fragmented and dislocated effect echoes Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, and the aphoristic, fragmented style of Nietzsche’s prose and command to listen more attentively to voices and memories transmitted through language. Again, the installation is so full that it wants to break open the form it is trapped in and points to another form, so l now wonder whether this work was a Pavilion or a model and program for something else.

The Brazilian Pavilion has been renamed The Hahawpua Pavilion, showing the installation Ka’ a Puera: We are Walking Birds, by the Tupi artist and activist Glicerio Tupinamba and the Tupinamba Community. The work comprises displays of ceremonial mantles. It was in this pavilion that l sensed that the Pavilion as a structure no longer worked, especially for stateless nation peoples. It generated an uncomfortable atmosphere of human zoos and global world fairs to show off the produce and conquest of global colonisation, counter to a work that shows anti-colonial struggles and indigenous resistance in Brazil. In many respects, the pavilion is an exhibition of European artifacts, since Europeans robbed existing mantles, and destroyed native communities. Here, the art activist’s quest was to recover the mantles and use the exhibition to recontextualize the cultural artifacts back into their original settings and ceremonial function, in effect recovering and reconstructing a destroyed culture and way of life.

The Lebanese Pavilion in the Arsenale, A dance with her Myth by Mounira Al Solh, a Dutch- Lebanese artist, is an installation structured around a built pier and boat, to remember, recover and reinvent the Phoenician myth of “The Rape of Europa”. Phoenicia, dominating trade and the seas, was the historic empire that occupied the same site as today’s Lebanon. This act of recovery sought to reclaim the myths and its representation from multiple sources, including that of the Greeks and Italian Renaissance artists or to contest and reclaim the myth back from Greek and Renaissance History. The myth is intended to link up Lebanon with Venice, another important sea-trading area. The artist’s objective is to recover the myth not just for Lebanon but for women, where women have not been offered their interpretation of the “Myth of Europa”. The artist reinvents the myth for women and for herself, by inverting the story where Europa abducts Zeus, which she does here around the reconstructed pier, using banners, paintings, video and masks, an open-ended search for language, concepts, representation beneath fixed history and existing mainstream culture, hegemonic history and reasoning, through sourcing imagery and practices common to peoples and cultures in the middle east.

The Belgian Pavilion – Giardini. Petticoat Government by The Collective: Sophie Boiron, Valentin Bollaert, Simona Denicolai, Pauline Fockedey, Pierre Huyghebaert, Antoinette Jattiot, Ivo Provoost is a well thought out and designed installation. The project revolves around the use of giants as folklore figures from regions in Belgium, France and Spain, links to carnivals, and traveling to Venice for Carnevale, to examine contemporary myths. This is then used to displace fixed positions, the conceptual and belief system that we are trapped in, to think about existing conditions, beliefs, and thinking, in a similar way to Gulliver’s travels and Rabelais’ surrealist narratives, to dislocate rigid propaganda and notions of the real. The Belgium pavilion is one stage in the journey of the project from Belgium to Venice comprising the unfolding generative process of the project. A production and exhibition site, presenting its newspaper publication on demand, film, exhibition area, and main central area with seating and raised platform where models or props of giants sit or rest, the project offers a glimpse, or slice of real-time processes. It is necessary to look to their other sources to research and understand what is happening, as their website provides information and documentation. The objectives of the installation are ambitious, relevant, and potentially far-reaching, hinting at the necessity for structural change, which l can only agree with.

There is a density, precision and, wide-reaching ambition to the program that out of necessity takes time to register and process, so l will summarise here the few threads that l understand because they appear to outline something very important that we need to digest if we are to go forward. One of the project’s objectives is to articulate the overall problems that exist now, because if you cannot articulate the problems as a totality, it is fruitless to propose a strategy to counter these problems. The umbrella of the problems falls under the neocolonial, neoliberal functions of art and the role of mainstream art to attack and dismantle other cultural forms. In other words, the problems exist inside art as it exists, with the corresponding thinking and ideologies linked to governmental policies. For that reason, they seek to displace traditional exhibition forms to open up possible paths to emancipation and reverse power structures.”

Two other projects that are taking place alongside the Venice Biennale take up the theme of neoliberalism and its relationship to art more directly. The fearless artist Christoph Buchel’s show “Monte di Pieta” at Prada Foundation, looks at corruption, money laundering and debt, and l draw attention to Buchel’s projects because he is one of the very few living artists examining the entity of Art in the West as a totality, shifting and changing that entity.

Mongol Zurag: The Art of Resistance, Historical and Contemporary Mongolian Paintings, curated by Uranchimeg Tsultemin, at the Garibaldi Gallery looks at the destruction of Mongol traditions during the Soviet era, and now the destruction of its environment, resources and culture through neoliberal economic policies. This is the first time that an exhibition has presented the history of modern and contemporary art from Mongolia, an overview of Mongolian thinking and art since the 19th century, and key players in reviving and reconstructing Mongolian contemporary culture.