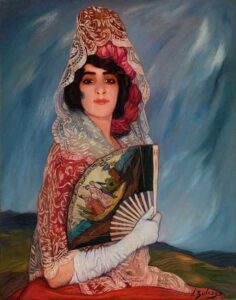

Susana Gómez Laín

Oil on canvas, (c. 1913)

After having my temperature tested, my hands washed in hydro-alcohol and my mask well adjusted I entered, full of joy and hope after a series of lockdowns. The exhibition “Invitadas” (invited) at the Prado Museum is an event procrastinated and yearned for, wrongly expected to be of a radical feminism. It not only showcases the works of important unknown women painters from the 14th and first half of the 20th century in Spain, but also exposes their general significance as muses in art, mothers, wives, workers, companions and even rulers. The curator also highlights their continual fight for recognition in all fields of society. Their attempt (the curators add a touch of modern reconciliation) at fair criticism, sarcasm, simplicity and even humour in the final exhibition can be extended to almost all women of the time and the majority today. The exhibition is an outstretched hand, an offer of friendship, a truce. This approach is achieved.

Most of the magnificent works shown have been rescued from the cellars of the museum, or other cellars, demonstrating, as a metaphor, that the supposed victory of women is still far from being achieved and that even in such an iconic and universal place as The Prado we are still just invited to have a moment of glory and then, probably, led back to the cellars. I hope it is not going to be like that anymore and that this sublime exhibition serves to open eyes and minds and inaugurate a new salon in the museum where the invited can stay for good.

The honesty of the curator in choosing the title was for me the most important distraction because it is probably going to be misunderstood. I would have preferred a pious lie like Missed or a declaration of mea culpa like Discovered, but this is just a personal preference.

But it seems that in this annus horribilis everything goes wrong for all and misunderstandings do not stop here. The show was launched with another mistake in trusting the Reina Sofía Museum’s classification of La Marcha del Soldado (A Soldier’s Departure) as a woman’s painting because the subject matter was condescendingly considered a family scene. In fact it is a canvas by a male painter, Adolfo Sánchez Megías, and was immediately retired as soon as the expert Concha Díaz discovered the error, though it had already hit the art headlines. Errors are human and, a bad that might do some good, this dance of identities and roles maybe serves as a proof that the difference in gender in art is not as visible on the canvas as it is outside of it.

The second error was the choice to put a reproduction of the oil on canvas Falenas by Carlos Verger Fioretti (1872-1929) on the publicity poster. Painted in 1920, it depicts a glamorous vamp of the time whose occupation is to escort a sugar daddy. A Falena is entymologically a moth of slim body, long legs and weak wings. Great comparison. This stereotyped version of a woman, added to the male authorship of the work, puts this choice at the apex of inadequacy. Why did the male curator choose this specific canvas among all the feminine wonders? Until we know, the choice stands as indefensible.

A third mistake is to show, in an exhibition promoted, or supposedly devoted, to women painters, the works painted by men, even though they are excellent works from famous artists like the Madrazo brothers, Ignacio Zuloaga, José Gutiérrez-Solana or Antonio Fillol, among others which, at least, depict women or female scenes. This focus has been highly criticised in the papers and

Publicity poster for “Invitadas”

on forums, with good cause.

For the rest, you will see magnificent art works in different media, painted on different surfaces: sculptures, footage, miniatures, photographs and decorative arts such as embroidery showing exquisite technique, delicate detail and great sensibility, many of them recognized as important pieces in exhibitions of the period or shown in the National Exposition 1887, or in the First Exhibition of Feminist Painting in the Salón Amaré in 1903 in Madrid, but still unknown. You will discover that most of the female artists came either from the nobility, aristocracy from outside Spain. Even Queen María Cristina was a remarkable oil painter, as were daughters, wives or close relations of male artists; this was the only way they had to get into the artistic realm, considered outlandish for them, like the French Euphémie Muraton, Cécile Ferrère and Hélène Feillet, protected by the Spanish Queen in exile in Paris, Isabel II, who was as bad as a queen as she was a good and rare fervent supporter of female artists.

I particularly liked the great oil painting depicting flowers and fruits by María Luisa de la Riva, the tiny miniatures painted on ivory or metal by María Tomasa Älvarez de Toledo y Palafox, and the oil on panel El Príncipe Imperial Napoleón Eugenio Luis Bonaparte a caballo (1880) by the Spanish-Italian painter Francesca Stuart Sindici - exquisitely painted and unusual for the equestrian subject matter, banned for women at the time.

Others I have to mention are the oils and pastels of Rosario Weiss (goddaughter and pupil of Goya), Julia Alcayde o Lluisa Vidal, and the sculpture of Helena Sorolla.

Many thanks for rescuing from oblivion and doing historic justice to the pioneer filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché, the first woman to direct a fiction film and a creator of magical short films. The best of all, for its topicality, originality, freshness, boldness and hilarity is the one called Les Résultats du féminisme (1906) where men and women change ordinary roles in society, giving rise to hilarious situations with a harsh critical subtext. Just brilliant and hidden for decades, it reminded me of some of the later Chaplin sketches. Please don’t miss it or any of the others screened.

A note: The pandemic, with the capacity restrictions, has allowed us to have a more intimate and quiet experience of the artworks and the spaces. Take advantage, it won’t last.

Volume 35 no 3 January - February 2021