LEARNING FROM THE MASTERS

By Bradley Stevens

When I was a young art student I remember walking with some trepidation from my studio in downtown D.C. to the National Gallery of Art. I had signed up to copy my first painting in this venerable museum, and was apprehensive at the prospect of working in front of throngs of onlookers. Nevertheless, I was determined to follow the long tradition of art students reproducing the Masters as a means to unravel some of the mysteries of painting.

For my first copy, I chose a small Monet landscape titled Argenteuil, from 1872. I always loved this painting. With luscious oil paint on a flat canvas, Monet somehow captures the feeling and spirit of a particular time and place. One can sense the stillness of a warm summer evening, as he stood painting on the bank of the Seine. A tall row of trees on the right edge of the canvas block the setting sun, casting the foreground into shadow––except where a few bold streaks of sunlight pierce the adjacent road. On the low horizon below a luminous sky, two sailboats lazily head home, their sails mirrored in the calm waters. In the distance, façades of the local village catch the last rays of fleeting light. To me it was pure magic. The scene was real, but it was more than reality. It was art. Every brushstroke, every note was perfect, like a Mozart divertimento.

From that moment on, it became my mission to learn as much as I could from history’s great artists. For the next five years, two to three days a week, I copied paintings from a wide spectrum of styles and time periods. I learned something different from every artist: Corot simplified the landscape into large masses and shapes, then skillfully added touches and accents to enliven the paint surface; Degas used gestural lines to emphasize human movement; Rembrandt deepened shadows with transparent glazes to give physical and psychological depth to his subjects; Gilbert Stuart varied the focus in his paintings, delineating some parts and leaving others indistinct; Sargent, the ultimate master of bravura brushwork, expressed so much with an economy of strokes; Cezanne stressed structural form to give his subjects magnitude and gravity. Without exception, every artist taught me that a well-conceived and balanced composition is absolutely essential.

Copying paintings has long been an accepted, and indeed, venerated part of an artist’s education. When in Rome in the early 17th century, a young Peter Paul Rubens copied The Entombment of Christ by Caravaggio, who based his Christ figure on Raphael’s The Deposition. His figure came from La Pietà of Michelangelo, who looked towards classical Greek sculpture for inspiration. In 1831, artist Samuel F.B. Morse (later known for his invention of the telegraph) worked seven days a week for two years on his 6’ x 9’ canvas, Gallery of the Louvre. In this immensely ambitious painting of the museum’s interior, Morse meticulously reproduced thirty-eight Old Master paintings. Morse’s motivation was to educate and inspire American audiences about the great art and culture of Europe. At this time there were no significant art schools or museums in the United States.

To paint well is hard ––very hard. Myriad considerations demand attention seemingly all at once: color, light, shadow, drawing, proportion, design, brushwork, texture, edges, harmony, perspective, spatial depth, movement, focus and more. Accomplished artists from the past have already confronted and solved these issues in one way or another, so why wouldn’t we want to take advantage of their expertise and learn from them? To do otherwise is to be ignorant, if not arrogant. I call it learning the “language” of art. Observation of nature alone cannot make a painting. Artists learn to translate what they see, and you see, with their eyes and imagination, into art. Looking at a print of a painting in a book or elsewhere is not sufficient. Such a reproduction is an untrustworthy two-dimensional representation of a particular painting with suspect colors owing to the limitations of printing inks. A painting is a three-dimensional object with many built up layers of pigment, thick with impasto in places and thin with washes in others. A copyist is required to be a detective of sorts, carefully deciphering clues as to what was painted first, second, third, and exactly what pigments were used to create the colors in the original.

I am convinced that much of what I know about painting, I learned from being a copyist in the museums. I’ll be the first to admit that copying something is vastly easier than creating the original idea. Nonetheless, it gave me a sense of confidence that I could at least technically produce a successful painting, which hopefully would translate to my own work. An unforeseen and added benefit was that people wanted to acquire my copies. In time, I developed a reputation for this work and received major commissions to copy paintings from institutions such as the White House, State Department, Smithsonian, Monticello and U.S. Capitol.

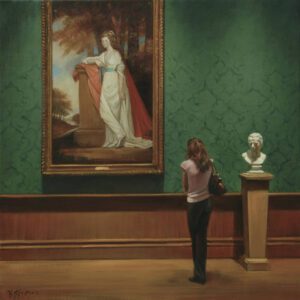

Of all the pillars of an art education, I’ve often worried that art history is the most neglected. I see art as a continuum. Each generation borrows and learns from the previous ones. While present day students might see the idea of copying as passé, I believe it is a mistake to ignore the past. Picasso famously stated, “Good artists copy, great artists steal”. The purpose of copying is not to mimic any one artist or style, but to gather ideas and be inspired by another artist’s work so that you can interpret them into your own. My own experience of copying paintings led to the creation of Museum Studies, an on-going series of original work featuring intimate scenes of people looking at art in museums. These paintings are my tribute to the great artists who have inspired me and to the museums that invite us to appreciate their genius.