I still know those cries of the soul. They lie at the breast and in the throat. The mouth wants to open wide and let them out, but all these are antiquities, yes, Jewish antiquities originated in the Bible in a biblical sense of personal experience and destiny. I remember. I must.

-Herzog by Saul BellowBecause I remember I despair. Because I remember I have a duty to reject despair.

-Elie WieselHumor is one of the best ingredients of survival.

-Aung San Suu Kyi

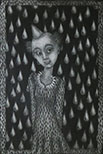

The faces are sweet and bitter, charming and grotesque, with expressions inoculated by a dreamy calmness. Enigmatic characters dwell in realms of fractured fables, mixed up myths, and bizarre fairy tales that scramble religious imagery, symbols and cultures with more than a little alluring grace for all their strangeness. The Dutch artist Bert Menco makes images that are elaborate theaters staged by his subconscious, filled with the illogical and surreal associations his mind invents. His work is related as much to particular 20th century traditions of Jewish narrative art as it is to the medieval imagery of Northern Europe. Two different exhibits present the range of Menco’s art and it’s deepest preoccupations. His show at Temple Solel in Highland Park reflects themes related to the artist’s Jewish identity and the tragedy of the Holocaust, while the Re-invent Gallery in Lake Forest displays a dazzling array of works that continue aspects of this theme while addressing the complexity of human and sexual relationships.

One of Menco’s influential precursors is Marc Chagall who was born in 1887 in the Eastern European city of Vitebsk, part of Belarus. Chagall’s early modernist works were filled with flights of fantasy and illogical transpositions that were rich with symbolic meaning. They expressed the precarious lives of the Jewish Diaspora, often relating the difficulties of their everyday existence with poetic humor and mystery. Many of his characters take to flying in the skies in an unstable and dislocated world that becomes a springboard to mystical fantasy. A tradition of fantastic and surreal art can be found in Jewish authors like Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bruno Schulz and Franz Kafka, for whom the individualistic “universe” of the artist-poet becomes it’s own introspective “truth” with it’s own “logic”, it’s own surreality. The “universe” has become dislocated and seeks to find deep purpose and meaning again, but through non-logical esoteric “truth.” Menco’s visual narratives owe much to this literary background, bridging past and present through subconscious fantasy and attempting to bind them, with all their lyrically absurd as well as rich implications, into his own poetic dream world. The face of Kafka in Menco’s The Golem is superimposed on the old Jewish cemetery in Prague. A chain of dancing figures in Rondo, beginning with life and ending with death, are overlaid on Menco’s enlarged self-portrait. Both compress meanings and symbols with a mingled simplicity and complexity. Fantastic scores of flying figures in Messengers, Fireflies, Suspended and The Origin of the World are attracted, like moths to a flame, around a central large female figure with whom they are trying to make contact. Each has a story to tell that is filled with emotional ambiguities, secrets, and spatial contradictions.

Menco’s work is also deeply influenced by the art of Northern Europe, particularly Flemish art. He was inspired to become an artist after seeing the prints of Rembrandt (1606-69) in his native Holland. Menco’s work absorbs much iconography from Christian medieval art, focusing a particular interest in the style of illuminated manuscript drawing and paintings. This medieval mood is reinforced by the “antique” look of the etching medium. His elaborate mezzotints, which work from a velvety dark surface through greys and into white, emphasize this medieval Gothic aura most effectively. Menco also admires work of the Belgian artist James Ensor (1860 – 1949) who is well known for his portrayals of bizarre masks that come to life as wildly grotesque caricatures. These peculiar beings are featured in humorous and excoriating satires: allegories about human stupidity, venality and folly. Menco’s imaginatively conceived menu of “tarot card” characters presents a parade of humorous allegorical subjects featuring Madonnas, harlequins, angels, devils, jesters and zoological hybrids. Like Ensor, Menco enjoys filling up every space in his painting and prints. The multiplication of faces, decorations, and symbols in backgrounds or borders lends a whimsical sense of mystery through their sheer obsessive repetition.

Prints shown at the community house of Temple Solel explicitly deal with the artist’s personal consciousness of his Dutch-European and Jewish family background regarding the Holocaust and WWII.

I was born just after the war that divided the century in half. My mother and her family survived the bombing of Rotterdam, though only she and my grandmother survived the Holocaust. My father’s immediate family was completely annihilated, but my father survived the war, rescued by French communists. My parents met while they were refugees in Switzerland; they married on May Day 1945.

(Contemporary Impressions: The Journal of the American Print Alliance A Self Portrait “Inside Out” By Bert Menco, Fall 1998 p.6)

Menco often uses collective historical, literary, or symbolic figures to confront disquieting and existential questions of loss and suffering perpetrated by the Holocaust. In the print Shylock, Acta Fabula Est (The Play is Over) the artist displaces the anti-Semitism inherent in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Veniceonto the “Final Solution” of the 20th century. Shylock and his daughter Jessica are reunited in a concentration camp as they join a ghostly mass heading to the gas chambers.

Their plight is heightened by the commanding finger of a guard pointing to their doomed destination and by the intense blackness of the mezzotint print surface. Bathed in dark despair, this work powerfully exudes an aura of collective guilt upon the perpetrators of genocide. Rotterdam, May 14, 1940 dramatizes the destruction of the city’s central church licked by feathery flames. Once again the elaborate burnishing method of the mezzotint technique adds an uncanny sense of haunting nostalgia and loss to the tragic scene. Arnhem, September 17, 1944 allegorizes the British air invasion of parachuting soldiers who took part in the tragic and failed Operation Market Garden. Both prints are filled with refugees carrying bundles, bags, children, babies, suitcases, and rolling wheelchairs and buggies. They are also a reminder of the tragic dislocation and up uprootedness that the Jewish Diaspora had to endure for centuries. There is an undeniable melancholic resignation in Menco’s figures. Even the parachuting soldiers in the Arnhem print look like helpless puppets on strings. These figures have internalized a sense of being alienated, isolated, and dislocated. The work keeps alive both a personal and an historical consciousness not only about the disastrous events of WWII but also subliminally about the rejection and persecution of the Jews in Europe throughout history.

In another print God the enlarged profiles of a man and woman gaze into each others eyes from opposite sides. A bearded man in rabbinical garb, God, stands between them, bearing a crate of decapitated heads on his shoulders. The profiled man wears a face of placid resignation while the woman expresses deep despair. Through a remarkably simple staging Menco expresses the weight and burden of Jewish history, it’s suffering, and the ultimate evil of genocide. In The Golem the enlarged head of the writer Franz Kafka is projected over an image of headstones, representing the old Jewish cemetery in Prague and where the historical figure of Rabbi Yehuda Loeb (1520-1609) stands with outstretched arms. It seems as though he has resurrected Kafka as the “Golem”, the contemporary representative of a long Jewish history who is called upon to write about existential questions that continue to haunt our modern conscience.

References to Christian and Jewish art and church iconography from Christianity abound. In Synagoga et Ecclesia a woman holding a Menorah representing the Jewish faith wears an expression of open innocence. “Ecclesia,” the Church, smiles slyly to herself while balancing a cross and sword under each hand, contemplating whether or not to use her inherent destructive power against her fellow sister. Surrounding them is a frame of fantastical faces: strange mascots from a gothic past. For all their elaborate and whimsical appearances, each face is cast in a shadow of gloom, with piercing expressions that seem to wordlessly ask if indeed real religious equality and justice can ever be possible. Behind Walls depicts a young man and woman in motley dress running joyously on top of a wall. Below crouch several men resembling the artist in old age in what seem to be the striped uniforms of concentration camp inmates.

They cover their ears as if as if to block consciousness of an unimaginable horror that will be their destiny. Two opposite pathways appear: either the horror of genocide will repeat itself or the chain of life will continue. There is also a latent sent of guilt and fear which the darkness of the past projects on the next generation.

The Re-Invent Gallery show continues some of the same themes discussed, but with a lively breadth of wit and humor aimed at the complexity of human relationships and the instability of meaning in myth and religion. In The Virgin Birth of Lucifer a “Madonna” holds a cute devil baby on her lap. In Adoration another “Madonna “in a feathered headdress and a spiny blue costume embraces a small green horse. Even as he pays homage to the art of the Church, Menco plays with the idea that faith based “truth” can be turned upside down by the pretenses of its own “logic.” The print Shedding turns anxiety into an absurdly comic phenomenon as four male characters are swamped by a whirlwind of hair flying off of their heads. Freckles presents the profiles of several sweetly becalmed faces defaced by a riot of spots. It seems as though a bad case of the measles has gone wild and decorated everything with a manic profusion of polka dots. Each image presents a way of comically and obsessively coping with disorder, uncertainty, and anxiety. A perceived world of absurd, unpredictable situations is confronted by humorous and fantastic twists of the imagination.

A great many works in the show emphasize complexities inherent in male/female relationships. Chagall’s art often expresses the theme of happiness and fulfilment in sexual union: it is sincere, simple and sensuous. The painting Annunciation presents a similarly themed fantasy. But sometimes Menco’s couples are frustrated from being able to find fulfilment. There is a strong desire for love and companionship, but somehow the possibility of intimacy and emotional contact is thwarted. In the astonishing print Pairs a gridded panel tells its story in a cartoon-like sequence. This kind of sequential storytelling is reminiscent of work of Charlotte Salomon, an artist who painted a “graphic novel” autobiography about her life hiding from the Nazis until she was captured and died in Auschwitz. In Menco’s graphic “story” a brilliant theatrical array of male/female conflicts is presented along with other humorous “pairings.”

Sometimes the body of one falls apart or exits the scene, sometimes one is upside down while the other is right side up. The dislocation of life has become too extreme for there to be peaceful resolution, but it does throw his actors into puzzling and fantastic situations. Women seem to be powerful figures that embody mystery in relationships. They have become both attractive idols and a source of anxiety for the male attendants trying to get her attention. Many of these small figures surround a single iconic women in works like The Origin of the World, Suspended, Death and Dunces, Cats and Mice, and Holding Off. The women are sometimes sly and designing but also wistful and sad. The men around her plead for attention, wishing to placate her melancholy, but to no avail. Women seem to be the ones with transformative or mystic powers while men are the audience and attendants to her alluring but often strange presence.

In the painting Shaman a bald woman tries to make some kind of desperate appeal to a kingly ruler in motley dress. Women with shaved heads often appear in Menco’s work, bringing up multiple associations. The shaved head of Joan of Arc from the famous 1928 film The Passion of Joan of Arc by Carl Theodor Dreyer is one source, but the image of a bald woman undeniably brings to mind the shaved heads of women from concentration camps. Both become symbols of religious persecution and suffering. Is the shamanic woman a wish fulfilment to be able to alter history as she pleads before the king? Does she embody mystic power that has been bestowed by her suffering, giving her an unworldly strangeness and otherness?

Utrecht-Chicago is a work about leaving Holland, the old world, and seeking a new start in a new land. The two cities merge in a divided landscape of buildings featuring two figures floating in the center. One is the artist as a young man with angelic wings, while the other depicts himself as an anxious old man in a wheel chair. They alternately symbolize the grief and depression of the past and the positive youthful energy of hope for the future.

Which path will be the artist’s fate? Will tragedy or good fortune prevail? Manipulation comically extends the theme of conflict in relationships and the question of who holds power and control. A master puppeteer manipulates a hand puppet that in turn manipulates others, with the smallest and least powerful ones engaged in passionate argument. The puppet play comically presents a shrewd critique of power and its excesses, its desire to control others with the predictable results.

Some of the small prints present memorably compelling messages in their imagery. Fifty Balloons depicts the artist leaping into space with fifty small faces on balloons attached to his back. Because he holds a party horn the work seems to be about celebration. But the many faces behind him seem to subliminally tell another story symbolizing memories of those from the past that he still carries with him. Musical Chairs symbolically presents questions about Christian religious history. A woman wearing what appears to be to be a nun’s habit dangles five children’s heads from strings that hover over four small bodies below. It is clear one child will lose – will not get a body for its head.

The “nun,” representing the church by symbolic implication, has the power over life and death in deciding the children’s fate, and plays with their heads as though it were just a game. The Rue de la Morosité (Street of Morosity) is an unforgettable image filled with acerbic and depressive rancor. A cluster of people with hollowed eye sockets walk down the steep perspective of a narrow street. It seems to be a specific memory of the streets where Menco grew up in Holland, filled with claustrophobia and depression about the tragic past which memory will not hide.

Like the contemporary artists R.B Kitaj and Irving Petlin, Menco presents consciousness about Jewish identity and history as seen through his own life and percolated through the uniquely imaginative, surreal and esoteric configuration of his subconscious. Chagall’s work became melancholic after WWII, unable to cope with the unspeakable murder of 6 million Jews and the loss of the rich culture they once spread throughout Europe. The melancholy in Menco’s work is an attempt to confront and mourn this profound loss. At the same time the imaginative power of the Jewish narrative tradition and surrealist modernist influences in his work present a path that can express the absurdities of life through humorous contradictions. Poetic and irrational “daydreams” become a means of coping with the tragedy of history and a way to recreate the world again from within oneself. The flexibility of Menco’s artistic identity comes from understanding his own personal history as a means of self-realization, a way forward that connects to life, survival and a way to endure.

Originally published in Neoteric Art

Diane Thodos

Diane Thodos is an artist and art critic who lives in Evanston, IL. She is a 2002 recipiant of a Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant and is represented by the Thomas Masters Gallery in Chicago and the Traeger/Pinto Gallery in Mexico.

Volume 30 number 2, November / December 2015 pp 13-17