For many of those engaged in Chicago’s art community, the work of the Imagists or the Hairy Who collective is a prominent milestone in the city’s artistic legacy. For others, this work plays second fiddle to the art historical moment happening in New York around the same time.

Some arguments have been made that collectors of Hairy Who continue to promote the work in an effort to at least bolster its market value if not place it on equal footing with more predominately known artists and movements.

This is after all, the most basic function of the art world. The exhibition “Politics, Rhetoric, Pop” at Kavi Gupta in Chicago featuring work by Chicago artist Roger Brown and New York artist Andy Warhol could be viewed with that same brand of cynicism but, regardless of where you stand, it manages to achieve something more thoughtful.

The parallels begin with the artists’ lives. Both were gay men who grew up in rural parts of the country and took interest in art at an early age. Their pursuits of art carried them to big cities where they not only established themselves as makers but also as collectors. Their work looks quite different at a glance. Walking into the exhibition we are greeted with one of the largest pieces, The War We Won, is a painting by Roger Brown depicting Boris Yeltsin, Mikhail Gorbachev, George H. W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan. Gorbachev and Bush are in the center shaking hands. This painting shows the distinct figurative style of Brown’s work whose degree of editorial authorship is something Warhol would strongly avoid.

Throughout the room, Brown’s well modeled but cartoon-like faces of familiar celebrities and politicians hover over the eye-popping backdrops of repeated color gradients. These accompany Warhol’s very graphic portraits and occasional printed still life, interiors, or landscapes. The stylistic range creates the sense that we are looking at a left-wing propagandist and a subversive ad-man.

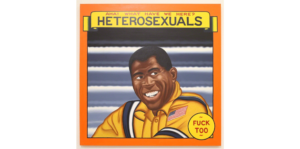

Brown may take on the role of activist with a piece Aha! Heterosexuals Fuck Too which cites Magic Johnson to dismantle the argument that only gay people are susceptible to HIV and AIDS. Warhol utilizes pop culture icons with as much agency but to different effect. In discussing the work with the gallery’s representative, Jessica Campbell, she described Warhol’s work as vacant by comparison to Brown’s. I agree but would argue that the same kind of vacancy exists in Brown’s work, just in a different location.

Throughout his paintings, the only figures that are given identities are famous celebrities or politicians. This rule would seem to apply to Warhol

as well. You can only be in a Warhol if you are famous or worthy of the fame that being in a Warhol can afford you. The only place for the average citizen in a Warhol is to be the person looking at the object. The function that the viewer of a Warhol performs is the same function that Brown narrates by including the tiny black figures in his paintings.

Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas, 10” by 8”

In Hollywood with Stars we see large versions of recognizable celebrities like Elvis or Marilyn Monroe towering over small, nameless black figures who are presumably the characters the viewers of the painting are more likely to relate to since they are neither Marilyn nor Elvis.

The parallels continue formally throughout the work of these two artists. Brown’s sense of manufactured color and repetition of forms echoes Warhol’s appropriation of reproducibility in printed ads and his ‘Factory’ studio model. We see both artists deal with architecture and landscape in different registers of cynicism.

Brown depicts his silhouetted figures in crumbling skyscrapers both in painted and sculptural form. In Warhol’s colorful Oberkassel, the surface glitters with diamond dust to simultaneously glamorize and assign a minimum value to the object.

No matter how many dots we can connect between these two artists, the conversation around the relationships between people, mass culture, and the complexity of industry seem the most poignant in this exhibition. Presenting these artist works not by chronology but rather by form and subject, “Politics, Rhetoric, Pop” gives us a glimpse into how two different visions of a historic cultural moment took shape.

Evan Carter

Evan Carter hails from Worcester, Massachusetts. He studied Painting at Mass. College of Art in Boston and is currently an MFA candidate in the Department of Visual Art at the University of Chicago

Volume 31 number 2, November / December 2016 pp 28-29