Frances Oliver

Courtesy of the American Jewish Historical Society at the Center for Jewish History

The artist Sven Berlin wrote a novel, The Dark Monarch, whose characters it seems were based on the St Ives artists he knew in the 1940s and ‘50s, thinly disguised. The book, now republished, had to be withdrawn, and a spate of libel suits followed, to great financial loss.

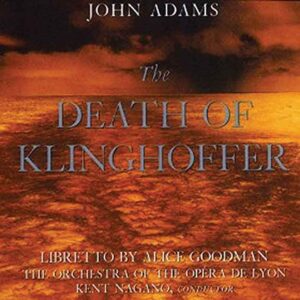

Things have changed much since those days. Now everyone, short of actionable defamation, is fair game for fiction, drama or cinema, and under her or his own name; not just known artists or royalty or celebrities but really anyone, even an obscure victim whose only distinction is a brutal death. The disabled passenger Leon Klinghoffer, thrown overboard in his wheelchair by the terrorists who boarded a cruise ship, became not only a figure in opera but gave the whole opera its name.

How did Klinghoffer’s family feel about this? His widow died of colon cancer soon after her husband’s murder. His daughters said, quoted in an article in the New York Times dated Sept 11, 1991:

“We are outraged at the exploitation of our parents and the coldblooded murder of our father as the centerpiece of a production that appears to us to be anti-Semitic, … While we understand artistic license, when it so clearly favors one point of view it is biased. Moreover, the juxtaposition of the plight of the Palestinian people with the cold-blooded murder of an innocent disabled American Jew is both historically naive and appalling.”

And in the Los Angeles Times October 19, 2014:

“We are strong supporters of the arts, and believe that theater and music can play a critical role in examining and understanding significant world events,” the daughters wrote. “The Death of Klinghoffer does no such thing … It rationalizes, romanticizes and legitimizes the terrorist murder of our father.” The family members said they were not consulted and “had no role in the development of the opera.”

“Terrorism cannot be rationalized,” the letter said. “It cannot be understood. It can never be tolerated as a vehicle for political expression or grievance. Unfortunately, The Death of Klinghoffer does all this, and sullies the memory of a fine, principled, sweet man in the process.”

Clearly no one consulted the bereaved relations before that opera was written. Did anyone consult William and Harry about the figure of their mother Diana in the film Spencer, or consider how they might feel about the graphic representation of their mother’s bulimia? Royals, I suppose, must come to expect such treatment; but how far should it go? In our postmodern politically-correct age where a word, a joke, touching on religion, race or sexual orientation can produce not only ‘cancels’ but penalties, why is it then that when artistic fabrications cause distress to simple individuals or their kin, the arts are exempt from blame? There are of course some decent examples of this dubious genre. Minemata for instance is a film with an important political message and one that showed respect to its originals. By and large however, ‘faction’ and ‘docudrama’, unimaginative art on the bandwagon of notoriety, where real people not just recently dead but alive appear clad in the author’s inventions and rub fictitious shoulders with beings dreamed up for the occasion, are a recipe for distortion and for lies.

Biography and autobiography can of course also lie. There are veritable battles between auto’s and bio’s, pupils debunking masters, wives raging at ex-husbands etc. But at least these profess to aim at a truth, whereas faction, held to no accepted yardstick, can cover a multitude of sins.

In his damning review of The Da Vinci Code film (The Guardian, 26 May 2006) which presents the ‘Priory of Zion’ European secret society as a fact when in fact it was a hoax, Simon Jenkins concluded, “Facts are sacred. If writers use them to disguise their fabrications, they are liars.” The lies of ‘faction’ and ‘docudrama’ may not often be as blatant or influential as the one cited by Simon Jenkins. But fictionalised images, especially in theatre or film, speak much louder, reach many more people, than sober attempts at faithful representation, and leave a picture behind which the real person or event may be lost forever in the public mind.

At a sale of old books I recently stumbled on a ‘popular’ biography of Mozart published in the 1930s, the first book of a later famous and acclaimed New York novelist, Marcia Davenport. Her mother was a renowned opera singer; Davenport knew the music scene and Mozart was her great love. The Mozart that emerges from her pages is a very different person from the clown in that silly film Amadeus; a complex and sometimes contradictory character, at once convivial and private, profligate and financially stressed, vulgarly funny but also conventional, berating wife Constanza for flirtatious behaviour, deeply religious, a loyal son and friend, an unprepossessing engaging little man imbued with the divinity of genius. Davenport put in a few, very plausible imagined conversations, all quite in tune with Mozart letters she quotes and I have read. In a preface to a later 1955 edition Davenport says she stands by her book but if she were to rewrite it she would leave the conversations out. In our age of faction and docudrama such modesty and scruple would be greeted with surprise and disdain.

Perhaps we should find a way to copyright our lives.