Matthew Nesvet

Matthew Nesvet

If, as many commentators say, the Venice Biennale is the Olympics of art, the international fair’s opening day features, in place of the world’s best athletes running through a stadium with torches, a parade of journalists, press assistants, and other curious ticket holders milling about the Giardini, the park grounds in Venice where the permanent national pavilions sit. Though the Biennale will last through summer, the size of the scrum of reporters and members of the public gathered around the artists and curators holding press conferences on the first day of the exhibition, and the different length of the lines to enter each pavilion, offer a rough approximation of the levels of public interest each national exhibit will garner in the days and months to come—and how likely are to win prizes.

Art Lantern, posted to the front of the United States national pavilion on opening day—a Wednesday morning in late April—waited for the pavilion’s press conference to commence and listened as two visitors from France, an older man and woman, exclaimed at the sight they beheld: artist Simone Leigh, representing the United States, had wrapped the neo-Palladian brick building housing the U.S. exhibition in an overflowing thatch roof that runs partway down the sides of the Guggenheim Foundation-owned building. “This looks like Africa, I can’t believe it,” the female told Art Lantern, laughing and smiling as she pointed to the Mozambiquan Raffia Palm that adorned the building.

Leigh, who, alongside British artist Sonia Boyce, would days later go on to win a Golden Lion—the art fair’s highest award—for her work in the international exhibition, The Milk of Dreams, used wooden pillars and a mostly unseen steel structure to stage the outside of the building in reference to the replica West African structures the French constructed—along with a replica temple at Angor Wat—for the Colonial Exhibitions. These were held in Marseilles in 1922 and—the event Leigh’s team cites—Paris in 1931, a year after the U.S. Pavilion opened, all part of a propaganda effort to show off the mission civilisatrice.

Leigh’s Façade offers a glimpse of the Biennale and similar fairs’ histories of exhibiting colonial dogma and national glory, pointing to how international exhibitions have long celebrated colonial empire and the nation-states that grew up within them. Leigh’s façade also calls attention to the ways the Biennale pavilions can add gloss, shine, and order to national projects that have a bloodier pedigree than the green Giardini reveals. It is a subject other national pavilions at the Biennale this year also explore, particularly German artist Maria Eichhorn’s excavation of the 1909 Bavarian pavilion building and its 1938 extension by the Nazis.

The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston collaborated with State Department officials to bring Leigh’s work to the U.S. Pavilion. In 2023, much of Leigh’s Biennale work will travel from Italy to Boston, where Sovereignty will comprise a major part of the ICA’s upcoming Simone Leigh exhibit. Eva Respini, Sovereignty’s co-curator and chief curator at the ICA, told Art Lantern that she and Leigh were already working on what will be Leigh’s first-ever museum survey show when, two years ago, Respini proposed Leigh to represent the U.S. at the Biennale. “Thinking it was a longshot” for the 2022 Biennale, when Leigh was selected, she and Respini “inverted the plans,” completing the U.S. pavilion first, then going on to work on the upcoming ICA show for Boston.

Leigh made each of the Biennale pieces new for the Venice exhibition, working in her studio in Brooklyn, where she makes ceramics, and at a foundry in Philadelphia to bring the larger-than-life show into existence.

Framed by the pavilion’s thatching and wooden beams, Leigh’s 24-foot bronze sculpture, Satellite, stands in the middle of the U.S. pavilion’s courtyard. Leigh based Satellite on D’mba (also called nimba) headdresses, which Baga people of the Guinea coast produce in the shape of a female bust to communicate with ancestors. Leigh replaced the bust’s head with a bronze-cast satellite dish.

The sheer scale of Satellite nods both to the work’s urgency—Leigh’s insistence that what she calls the Black Femme body stand on the Giardini without being overshadowed by the nation-state architecture surrounding it—and the actual cost of constructing the bronze figure and transporting it to Italy, a massive expenditure of national wealth that impresses on viewers the power of the U.S. government and the foundations supporting the U.S. pavilion. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, for example, which owns the U.S. Pavilion, last reported holding more than $200 million in assets. Much of the Guggenheim Foundation’s wealth comes from minerals and rubber extracted from plantations and mines in the Belgian Congo, Bolivia, Mexico, Alaska, and Colorado in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through colonial mineral and land concessions. Leigh’s work in Venice, partly powered by colonial extraction and the brutal labor conditions and land expropriations that accompanied mining in Africa and the Americas, also guides viewers to attend to the fraught histories of colonization and enslavement, particularly the dehumanizing displays of cultural power and violence that the colonial empires wrought.

Lacking the same resources, many countries’ pavilions are sited at the Arsenale, a complex of former shipyards and armories a roughly ten-minute walk down the waterfront from the Giardini; while others are at sites scattered around the city. (Of the just-named places whose mineral wealth helped fund the U.S. pavilion, Bolivia rents space in the Cannaregio district for its pavilion, while Mexico’s exhibit takes place inside the Arsenale. There is no Congolese pavilion at the Biennale, though at the Giardini, the much-lauded Belgium national pavilion show, The Nature of the Game, prominently displays Congolese children playing in mountains of mining waste alongside scenes filmed during children’s games in Afghanistan, Belgium, Hong Kong, Mexico, and Switzerland.)

Inside the three-room U.S. Pavilion, Leigh’s sculptural works—all originally produced for the Biennale—gesture to sovereignty, the show’s theme. Through the female form especially, Leigh explores how autonomy and ‘Black femme’ being can be embodied and seen in the wake of slavery and colonialism. Last Garment, a bronze and metal figure, was inspired by a photograph of a laundress working in Jamaica in the late nineteenth century. The original photograph assisted the British colonial government to circulate the trope of a stereotypical loyal, dutiful Jamaican worker the government at the time used to promote the island for tourism. Leigh’s sculpture interrogates the history of how colonialisms were figured, recasting female labor as both solemn and dignified.

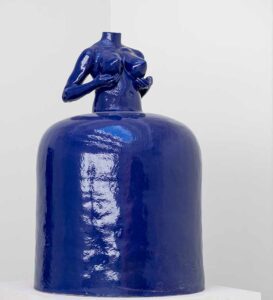

Elsewhere, with the glazed stoneware, Jug, Leigh similarly rescales the human figure, creating two enlarged “face vessels,” a stoneware artform that a group of both enslaved and free African American potters living in Edgefield District, South Carolina invented.

Sentinel, a sixteen-foot elongated female form that Leigh cast in bronze, sits in the Rotunda; on opening day, dozens of visitors make their way around the figure, which Leigh created inspired by her study of anthropomorphic African power objects and Zulu fertility ladles. Leigh’s sculpture, which, according to Respini, Leigh made to measure for the rotunda, encodes layers of meanings about female bodies, fertility, caregiving, and consumption into the figure. Standing beneath Sentinel, Respini says she feels a sense that viewers, as well as Leigh’s other work at the Biennale, are “under [Sentinel’s] protective gaze.”

In the next room, Leigh exhibits another cast bronze figure, Sharifa, a portrait of the author Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts, alongside Conspiracy, a short film that depicts the sculpture’s making.

Not all parts of the U.S. Pavilion are on display at the Giardini. At the end of the Biennale, Rashida Bumbray, Director of Culture and Art at the Open Society Foundation and a curator who has worked with Leigh for many years, will convene Loophole, a large gathering of Black Femme thinkers. Bumbray, who spoke to Art Lantern about Loophole, called the convening a “culminating artwork” for Leigh’s exhibition; it will bring together in Venice some of the Black women artists and intellectuals who “make [Leigh’s] practice possible.” Loophole follows Loophole of Retreat, a 2019 gathering of Black female artists and intellectuals at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Much like Leigh’s sculptures, Loophole will foreground collaboration—across generations, places, and academic and artistic disciplines. Its authorship is also multiple. Leigh is “committed to authorship,” Bumbray says, and made space for others—Bumbray; author and literary scholar Saidiya Hartman; and a long list of seminal Black female thinkers and artists to not just take part in the Biennale but also claim partial authorship of the American Pavilion show through Loophole.

“Not everyone can come to Venice,” Respini, the ICA chief and pavilion co-curator, told Art Lantern. That is why it is really important that audiences… can see Leigh’s work in [the United States] next year. According to Respini, “the U.S. pavilion will form the nucleus of the larger survey” exhibition when it opens at the ICA in March 2023. The survey will join Leigh’s work for the Biennale with works from 20 years of Leigh’s career, allowing audiences, first in Boston, then in Washington, D.C. and nationally, to, in Respini’s words, “see the throughline of [Leigh’s] work, see a visual language, and see the consistency of her concerns.”