Mark Bloch

While Fluxus has always been acknowledged for its diversity, Out of Bounds: Japanese Women Artists in Fluxus (October 13, 2023-January 21,2024 at the Japan Society in New York highlights four female artists who came from various parts of Japan to New York City in the early 1960s and became influential participants in the Fluxus movement. Directly resulting from Curator Midori Yoshimoto’s book, Into Performance, the exhibition shines a New York spotlight on four Japanese women fluxus artists and their unique contributions within the Fluxus movement to the art world through four separate utilizations of avant-garde strategies

In the beginning, Fluxus was not an art movement but more a collective of outsider anti-artists united not by style but by their allegiance to boundary busting and experimentation, leading naturally toward diversity. While the word ‘bounds’ in the exhibition’s title, conjures up images of women busting out of shackles to take their overdue place on the world stage, Fluxus has always been remarkably inclusive, a cross-racial, international movement featuring many women. The contributions to Fluxus by these four east Asian matriarchs-to-be in this long overdue show felt timely and important as we continually question the parameters of art making. Yoko Ono, featured in this show, was present when the word “Fluxus” was initially thrown around by founder George Maciunas as a label for what interested him, interpreting the word, Fluxus, meaning flow, from Latin. Maciunas said that the movement would promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promoting living and anti-art. The American Alison Knowles, an active participant in the first Fluxus activities that followed, broke ground for what many future female Fluxists and all future Fluxists and many non-Fluxists would do. Fluxus was concerned with manifesting new intermedia ideas about art. So while scholarship has been quick to point out in recent years “the membership of Fluxus was diverse and included many women, people of color, and queer-identifying artists” and that “Fluxus was more inclusive of women than any other avant-garde movement in Western art history,” turning the tide, the differences between what Fluxmen and Flux- women did was not as significant as what Fluxus did in relation to the activities of their peers internationally in the late 1950s and early 1960s before ideas like

Fluxus, The New York Correspondence School, Pop, Minimalism and Happenings had names while the rest of Fluxus history was slow to be accepted and appreciated for its innovative approaches.

In her essay in the 1993 catalog for In the Spirit of Fluxus at the Walker Art Museum, art historian Kristine Stiles paved the way for later feminist perspectives on the group and beyond as its ideas moved toward its tentative embrace by the mainstream. While the Tate Museum has cited the Fluxus dedication to a “diverse range of art forms and approaches” that no doubt contributed to an acceptance of whomever could get the job done without regard for their ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, MoMA specifically zeroed in on the fact that “female artists who helped shape Fluxus aesthetics … developed in the decade leading up to the women’s movement, and the prevalence of female participants in its diverse activities was unprecedented.” Sara Seagull, a designer and artist active in Fluxus said, “I did feel that Maciunas was non-gender oriented, that he really believed in people who had the ideas that fulfilled his vision – and he was extremely egalitarian about letting women work, letting men work, letting misfits work, for him or with him.”

Within Fluxus, controversy existed between the views of several women artists adjacent to Fluxus activities exemplified by Charlotte Moorman, the creator of fifteen Avant Garde Festivals between 1963 and 1980 and Carolee Schneemann, the important performance artist and maker of assemblages. Schneemann has cited reasons why she never was officially part of the group including, “the rather harsh judgments of Fluxus in terms of explicit sexuality” and, referring to “Fluxus —where explicit self-depiction was considered incorrect.” Perhaps it was indeed the ground-breaking psychological content of her important early pre-feminist works that kept her estranged or perhaps something more interpersonal. Referring to Fluxus-founder Maciunas, Jill Johnston, the 1960s critic for the Village Voice speculated: “Eric tells me GM really liked Japanese women, that they didn’t threaten him … that women like Carolee terrified him.”

Curator of this Japan Society exhibition, Midori Yoshimoto, has written informatively of the four women this show was about: “Unusually courageous and self-determined, they were among the first Japanese women to leave their country to explore their artistic possibilities in New York. While some other Japanese women artists left Japan around the same time … these (four) artists … departed from traditional art making toward unconventional art forms such as performance art … in which artists employ their own bodies as means of artistic expression,” citing, “…the transformation of these artists’ lifestyle from that of traditionally confined Japanese women to that of internationally active artists.” continuing, “In its expanded definition, performance here suggests the (four) artist’s self-empowerment through the acquisition of their artistic language and their ability to articulate that language. Through tracing these artists’ transformations, this study aims to illuminate their experimental spirit.” Takako Saito from Sabae in Fukui Prefecture came to New York in 1963 and left five years later in 1968. Mieko Shiomi, originally from Tamashima, a small town near Okayama, and Shigeko Kubota from Niigata in northern Japan, arrived together on July 4, 1964, coincidentally the American holiday of independence. Mieko left quickest, 365 days later before her visa ran out, while Shigeko, like Yoko Ono, never left. She and Yoko Ono both became New Yorkers for life, remaining permanently linked to Fluxus despite moving on to other things including their roles as wives and teachers—Ono to John Lennon and Kubota as the partner of Korean videographer Nam June Paik. Ono, from an upper-class residential neighborhood in Tokyo, moved to New York to attend college, married a fellow avant-garde musician, Toshi Ichiyanagi with whom she headed back to Japan from 1962-64. She later settled into an apartment in Shibuya with her second husband, Tony Cox, after suffering a mental breakdown due to an unfavorable review in Japan of her musical experimentation.

During that period, Ono played at least small parts in the other three womens’ stories. Presenting her work and events at the Naiqua Gallery in Tokyo in early 1964, Ono enlisted Kubota, and Shiomi to participate. In April, Kubota reciprocated the favor in another piece. Meanwhile, Saito was introduced to Fluxus founder George Maciunas through the Japanese artist Ay-O, who had met him through Ono in 1961.

Not only Ono and her first husband but the experimental Flux-musicians-to-be Paik, Yasunao Tone and Takehisa Kosugi were instrumental in alerting George Maciunas in NYC, the Fluxus founder, to the unorthodox musical goings-on in Japan as the 1960s began. Ono had helped Maciunas finalize the choice of the Fluxus name before departing for her homeland with Ichiyanagi in1962, unaware she’d remain until 1964. Shiomi and Kubota eventually travelled the other way, joining Saito, who had made the trip a few months earlier and had ended up assisting Maciunas—pasting labels on his earliest art products and participating in Fluxus mailings. The three women continued activities together, famously eating, shopping and preparing food for nightly “communal dinner events”—first with Maciunas and then others. Male Japanese artists such as Tone, Kosugi and A=yo would later join them, not only for dinner but also in Fluxus as it entered its middle period. Previous connections A-yo and Saito in Sōzō Biiku Kyōkai (Society for Creative Art Education) in the 1950s, Kubota and Kosugi, linked romantically in Japan, and Kosugi-Shiomi-Tone, in the avant-garde Group Ongaku, strengthened intercultural network bonds. Because work by Shiomi and Saito are seen less, I enjoyed the chance to see lots of it, in depth, here. Kubota and, of course, Ono have been more visible. Kubota passed away in 2015, then was featured in a show at NYC’s Museum of Modern Art in Aug 21, 2021–Feb 13, 2022 and in Japan, Viva Video! at Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo which traveled through February 2022. Kubota, the inventor of video sculpture developed her art form based on Fluxus intermedia ideals as Mrs. Nam June Paik, beating her influential husband to the early sale of a video artwork to New York’s MoMA.

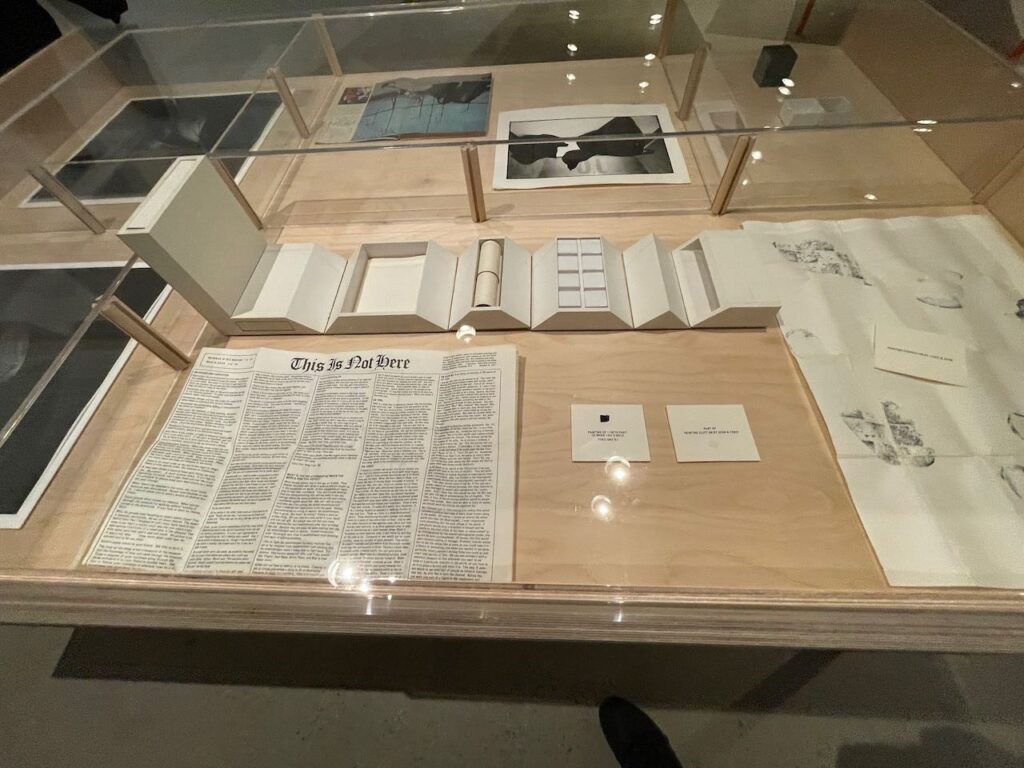

MoMA produced a major Ono show in 2015. Ono’s Music of the Mind at the Tate Modern in London in 2023 made 200 of Yoko’s most famous pieces unavailable for this exhibit, requiring The Japan Society’s guest curator Midori Yoshimoto to exercise inspired curatorial vision to present rarely-seen, lesser-known works to complement and bolster a continuing understanding of Ono’s iconic imagery over the years using what was available—highlighted by the usual boxes, bags and bodies—including Bottoms (Fluxfilm #4) and her famous Cut Piece.

Out of Bounds provided a sense of Ono’s early life including two marriages that corresponded with her Fluxus interactions, documented in Japanese magazines, posters and photos. Lennon, too, became a bonafide Fluxus artist, hinted at by Ono’s Everson Museum Catalogue Box (1971), designed by Maciunas and seen here which included participation by Lennon. While Ono has been important for many reasons and many decades, Fluxus remains a lesser-known anti-art force that deserves the ever-increasing fame it receives. Ono has done the world a favor, trumpeting and paralleling Fluxus life-art, performance, and Zen tendencies, always accompanied by humor and irreverence, like Dada before it. The culture got wind of Fluxus ideas when Yoko and Lennon married. Even if everything Ono touched hadn’t made it impossible to ignore, Fluxus is now better known to the mainstream, due to its merits and time passing. Even when denied its due, the crowd pleaser Yoko now shines deserving light on Shiomi, Saito, Kubota and all of Fluxus, evidenced by the robust attendance at the Japan Society’s elegant show.

Resonating with 60 years of Fluxus, this exhibition was organized by Tiffany Lambert, the Japan Society’s curator with Ayaka Iida, assistant curator and their star guest curator Yoshimoto, a professor at New Jersey City University who literally wrote the book on this subject back in 2005, establishing herself as the specialist in such matters. Their exhibit highlighted the effect each of these four Japanese women had on Fluxus and that Fluxus had on them—and their work. A rich, new overview of Fluxus thus emerged—evident in central rooms deconstructing The Collective’s whole. Flux-kits, suitcases and boxes with selected flux-objects fanned out in the glass-covered red and natural wood vitrines that delicately nestled in this show. Bound Flux-year- books and other collaborative book projects such as Fluxus 1 (1964) or A Tribute to John Cage (1987), short flux-movies by Ono and Shiomi projected across the gallery space, posters and examples of cc V TRE, the Flux-newspaper, hung sandwiched between plastic sheets for reading in all directions, with both sides viewable. Every example made Maciunas’ imaginative graphic design, layout and labelling skills evident.

Kubota’s minimal collage-objects, 1965’s Fluxus Napkins, red, with magazine cut-outs of a woman’s mouth, were called out in this collective hub, as were Fluxus Pills, 1966, her clear plastic box of empty capsules, ironic pointers to Maciunas’ health challenges. Nearby was Kubota’s travelmate Shiomi’s Music for Envelopes and her 1965 Water Music, glass containers for providing shape to wetness.

In adjoining rooms, surrounding the entrance and hub, the four featured artists’ œuvres’ could be explored individually, beginning with Saito’s considerable acumen in graphics, drafting and illustration that echoed and complemented that of Maciunas. A rare and colorful 1966-68 oil painting of the various members of the group conveyed an obvious fondness for the social aspects of New York Fluxus, within which objects, performances, photographs, printing and lettering were utilized to usurp painting and even collage. (Perhaps not coincidentally, Saito’s close friend Ay-o, her entree to the group, was also an outlier in this area: a utilizer of paint and ink in two dimensions when he portrayed rainbow imagery, supplementing his boundary-pushing tactile boxes.)

But it was imperative to witness and single out Takako Saito’s role in establishing the visual aesthetic of Fluxus here, not in painting but in something akin to feng shui or fusui. Surely Maciunas was the keystone but if there was a Japanese design element that the Lithuanian was in favor of from the start, and there was, it manifested powerfully through Saito’s delicate, dedicated practice: a facility with tools and her placement of elements like labels, learned from and developed in her work with George—often on the spot but always spot-on. Another George, Brecht, influenced her appreciation of the playful in Fluxus’ look and feel, spotlighted here in etchings, adorned cubes and most prominently, her multi-sensory chess sets, seen here in many forms. Finally, her large Takako’s Music Shop (2000) offered a colorful variety of musical/visual/performative composition possibilities such as seed pods to be released to the wind. Dozens of pieces were compiled in a free-standing Flux-kiosk.

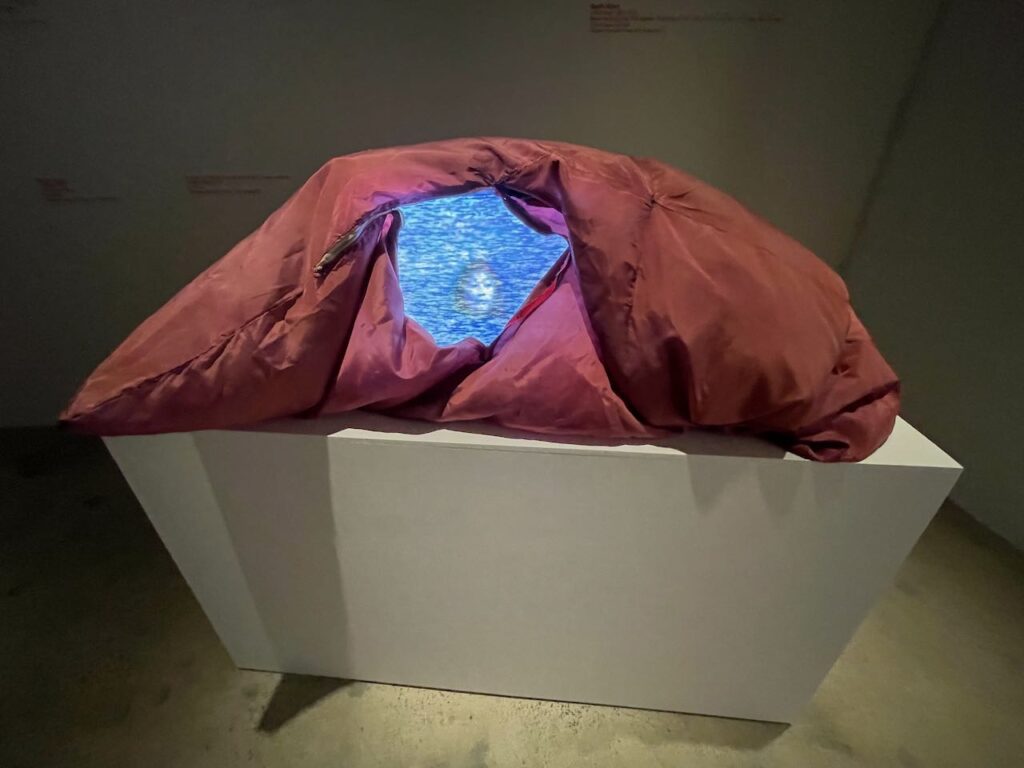

Saito’s extensive work with chess was echoed by the others. Ono’s White Chess Set (1966) created mono-confusion with a poeticism reminiscent of her book Grapefruit while nearby Video Chess (1975), Kubota’s video sculpture, a horizontal video under glass of Marcel Duchamp playing chess, doubled as a bottom-lit chess board admirably scattering the TV energy often emanating from Shigeko’s unique work.

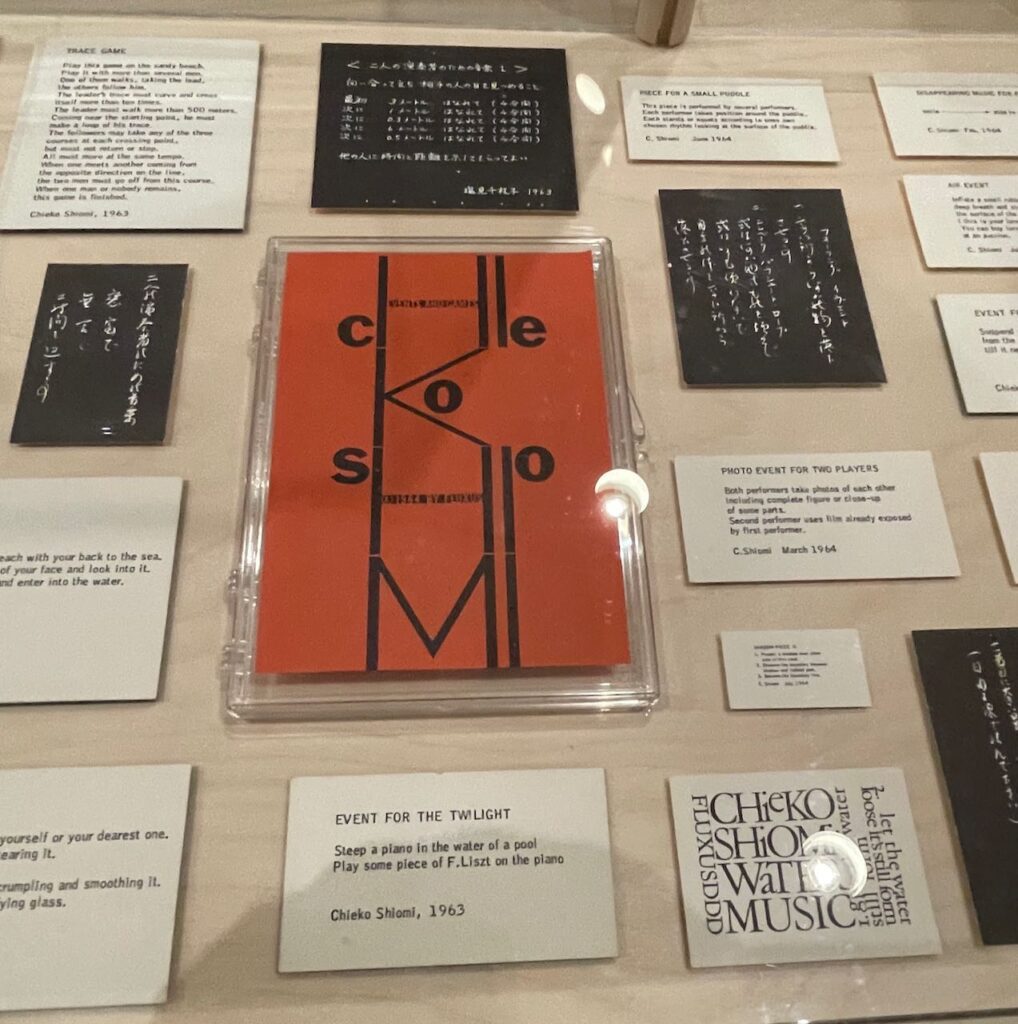

Saito’s game-like cubes also had parallels in Mieko Shiomi’s Fluxus Balance (1993), her 1963 compilation Events & Games of 21 offset cards, produced first in wooden and, later, plastic boxes by Maciunas and finally important works completed after she left New York in 1965 with only four seen to their fruition by Maciunas, her nine Spatial Poems. The nine Spatial Poems, all seen here in some form were No.1 Word Event (1965); No. 2 Direction Event (1965); No. 3 Falling Event (1966); No. 4 Shadow Event (1972); No. 5 Open Event (1972); No. 6 Orbit Event (1973); No. 7 Sound Event (1974); No. 8 Wind Event (1974) and No. 9 Disappearing Event (1975).

Shiomi had called her early work, unknowingly parallelling early pre-Fluxus ideas, ‘action poems.’ The approach to Mieko’s area included black and white Japanese television news footage of her work as the only female in Group Ongaku, blowing soap bubbles to translate musical concepts into physical expression. Like Ono, Shiomi was a late 1950s trained musician, with strong ties to classicism, that migrated rapidly in Cagean directions at the precise moment Fluxus was manifesting in New York. During an improvisational session of the Ongaku group, when Shiomi tossed keys toward the ceiling to signal a mood change with the noise, she later described that it unleashed in her an awareness of music as action, not sound, in time and space. This change in perception led from time intervals created with keys to later classic projects like Event for the Late Afternoon in Okayama (1963), a hanging violin slowly lowered to the ground.

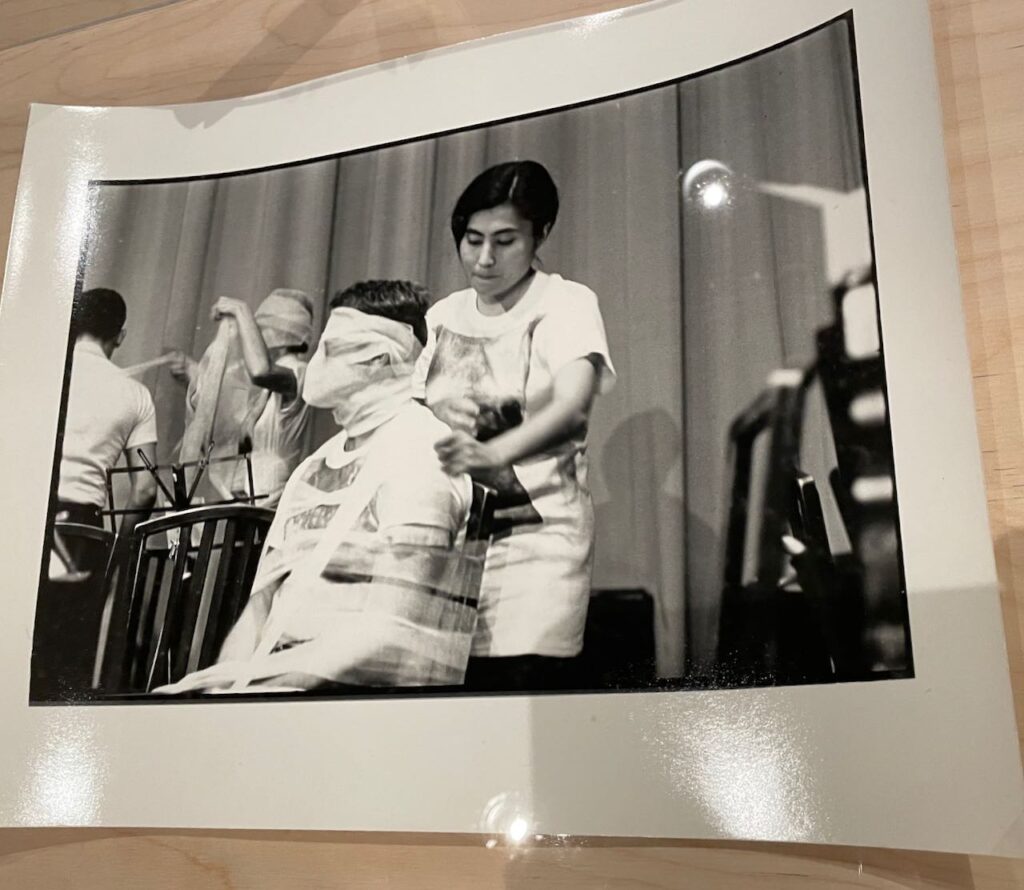

When Maciunas prepared an unrealized Tentative Program for the Festival of Very Early Music, Ichiyanagi and Ono first made him aware of Shiomi, even before the first Fluxfests. Shiomi, with Kubota, then visited the Ichiyanagis in Tokyo in 1963 where Shiomi, in turn, first saw Brecht’s scores and began calling her pieces events. Soon after, Maciunas purchased Mieko’s Endless Box (1963), thirty-four nested paper boxes. That sale funded Shiomi’s travel to New York accompanying Shigeko, who previously was to be joined by her reluctant romantic partner Kosugi. Kubota donned a large trunk and mailed a letter-scroll to Maciunas, both seen here as art objects animating an important Fluxus moment. A cloth bag sewn by Kubota for an earlier Kosugi performance was also dramatically displayed, highlighting that period. Rare photos of Kubota’s early Japan events were also revelatory. One year to the day after she and Shiomi arrived, notoriety arrived for Kubota on July 4,1965 in the form of her Vagina Painting, performed at the Perpetual Fluxus Festival at the New Cinematheque. Despite stage fright, before a group of only ten or so Fluxus artists, Kubota, with a brush attached to her panties, squatted and painted blood red abstract forms on paper spread across the floor. Reminiscent of menstrual blood, geisha references and Asian calligraphy, some saw it as a critique of macho action paintings by Jackson Pollock or Yves Klein’s use of females as painting tools in his 1960 Anthropometrics. Others were reminded of Zen for Head, a straight black line performed by Paik’s hair dipped in sumi ink mixed with tomato juice at an early Fluxus event in Wiesbaden, Germany in 1962. Kubota’s stunning one-time-only event lives on in photographs taken by Maciunas; freeze- frames of iconic pre-Feminist art. Peter Moore’s 1964 contact sheets of Kubota’s preparations seen at the Japan Society’s exhibit freshly illuminate the work which she chose never to perform again. She was propelled instead to video-document her life diaristically a la Jonas Mekas.

According to the curator Yoshimoto, “In her essay in the 1993 exhibition catalog In the Spirit of Fluxus, art historian Kristine Stiles discusses the feminist implications in Kubota’s Vagina Painting for the first time. Stiles asserts that Kubota’s performance ‘redefined Action Painting according to the codes of female anatomy.’ “She continued, “In conjunction with the celebration of Independence Day, Kubota perhaps intended this performance as a declaration of her independence from her past and Japan’s male-dominated artistic conventions … Kubota suggested a clever pun between human procreation and artistic creation by using the vagina as an artistic medium. Since Stiles’s analysis, other art historians reinforced the feminist reading of Vagina Painting.” Kubota, Ono and Shiomi had each contributed to the Hi-Red Center group’s 1964 Shelter Plan. Kubota later edited the 1965 Hi-Red Center Poster in her role as the Fluxus “vice-president,” a title Maciunas lovingly bestowed upon her.

I was honored to be part of Mieko Shiomi’s Spatial Poem Number Five: Open Event. The entrance to the exhibit featured dozens of little doors—divided by continent—that contained answers to Shiomi’s recent query to document and send her something that was “opened.” I was delighted to participate and it was nice to see a contemporary rendition of this piece that originally took place in 1972. In fact, I was very grateful to see documentation from all nine of Shiomi’s Spatial Poems displayed here as well as a slide show of mailed responses received in the 60s —after she returned to Japan from New York. I have always seen her Spatial Poems as landmarks in mail art and social communication as art.

Finally, a word about the performance art of Takako Saito. While her additions within the world of Fluxus objects were indeed significant, the curator of this show, Midori Yoshimoto, pointed out in her book Into Performance, Saito experienced a string of unfortunate circumstances and near-misses around events, preventing New York audiences from experiencing her work ideally when it was meant to be. The sad tale of events reads like an amusing Fluxus gag, an art prevention machine, as it were. During her first New York City stay, all of Saito’s planned official performance opportunities during her residency fell through, leading to a kind of fateful art of absence. First, Saito’s performance at the Café au Go Go, a weekly event organized by Brecht and Robert Watts, was announced as a jazz concert by mistake. Next, Saito declined a performance at Al Hansen’s loft due to a scheduling conflict. Then in 1964, a Saito performance to be staged by Maciunas was postponed three or four times due to problems securing the venue. Finally, on January 8, 1965, Amusements, part of the Perpetual Fluxfest, Saito’s audience-participation games, were cancelled due to the financial problems of the Washington Square Gallery.

Saito’s first public performance, influenced by her Manhattan years, did not take place until 1971, three years after she left the USA for Europe. Her overlap with New York Fluxus seems to have paradoxically run the gamut from the deepest possible influence to a beautiful but melancholy invisible non-participation. Saito’s friend Shiomi even suggested a mail art event, Postpone Piece, to make up for one non-occurrence. Takako created announcements for a fictitious Popcorn Theater that followed. Saito later created another mail event by sending wooden cubes inscribed with sentences including, Event Disappeared into the Bottom of Pacific Ocean. Thankfully, Saito went on to become quite a loved and effective performer in Europe and elsewhere, highlighted in photographs and video in this show.

For all four Japanese women, as well as their curators, the art in evidence at the Japan Society was created out of what was there but also what was not. The fact that it has taken decades for this show to materialize is a monument to a once missing respect for their roles as important artists. But Out of Bounds: Japanese Women Artists in Fluxus had the last word as one of this New York art season’s highlights.

Out of Bounds: Japanese Women Artists in Fluxus October 13, 2023—January 21, 2024 Japan Society Curated by Midori Yoshimoto. Organized by Tiffany Lambert and Ayaka Iida, Assistant Curator