“… I look upon that inward eye

That is the bliss of solitude…”

A famous quote, though some scholars believe the sentence of which this is a part was actually suggested by Dorothy, not William, Wordsworth. But the inward eye, that part of our brains that plays with images and re-imagines what we have seen, has been the topic of conversations among poets and thinkers for the entirety of our attempts at nationhood. It is precisely because we have thought so long and hard about what it means to ‘think’ about things that we can see so many instances of cross-over similarity between cultures, across the ages, and into contemporary art which hungrily seeks out older traditions to feed its insatiable appetite to bring to market anything that can be sold as ‘not having been done before’.

This inward eye that is wholly informed by the five senses and nothing else, that intuits almost nothing while believing itself capable of intuiting just about everything if given enough sensitivity to the metaphysical as well as the physical; an eye that deludes itself that what it experiences is, therefore, known while even Plato could understand that we know very little about the world around us through our senses. Our knowledge is at best a workable hypothesis that is good enough to get us by. An inward eye that is more attuned to the survival of the animals that we are in a hostile world, than in deriving universal meaning. For our senses are designed to get us through the moment, the hour, the day and not there to plan ahead 80 years. Science has been teaching us all we have missed and never known before and as Einstein so perfectly outlines, the more we know the more we discover we don’t know.

And this almost fabulous facility is all we have to engage in creating commentary on our existence, something we call the arts. All of them. For on this ground they are all equally hamstrung. So what can we make, what can we create, with senses that are limited to the visible world, the audible world, to the ‘safe-to-touch world? If each individual defines the world differently, however small those differences are in terms of colour perception, hearing, smell, touch and taste, where can we find anything that is truly universal and even if we could, is the attempt worthwhile? After all we are getting by and creating an immense series of cultures that have enough meaning to pass onto generations, so why do we want more?

Obviously we can attune to some extent to each other, for the differences in our senses are not a million miles apart, but atomic size differences tend to make all the difference. For while Greenberg asserted that paintings are two dimensional, they are, given the thickness of paint and paper, actually three dimensional and that makes a deference to how photons bounce off them into our eyes. And if we truly are walking around in our heads, creating our unique universe, separated while close to everyone else, how can we define the ‘experience of art’ that includes us all, and would an attempt at a definition have any purpose?

Actually, it doesn’t. Having written art criticism for only five years and read a century worth of thinking, the first fact to note is that assumptions have to be made before one even starts to talk about art and those assumptions, like all assumptions, can always be challenged. In addition, art has been played as a political and financial game for so long we may well have lost sight (forgive the pun) of anything in it that is not faked to some degree. The only honest thing we can say, without fear of being shot down, is that we have an appreciable impulse to create that some of us cannot, and don’t wish, to disadvantage.

But all art is a piece of foolishness. Because it is human it commences as a flawed conversation that can never be wholly understood or fully communicated. Like all our ways of thinking it is, at best, our attempt to create and pass on meaning while knowing we cannot be accurate. Unless we create within such restrictive assumptions as those of the Academies, that universal meaning instantly vanishes.

So we come down to knowing that any work of art is a personal message, skilled or not, that never gets out of its bottle. The inward eye always stays inside and is, as Wordsworth goes on to say ‘… the bliss of solitude…’

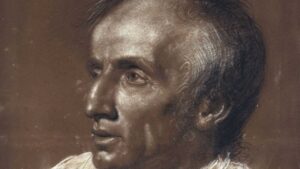

We carry galleries in our heads and I can be certain of one thing, mine is not yours and neither of us can see Rembrandt’s.

Volume 35 no 3 January – February 2021