Stephen Lee

Left to Right, Top to Bottom: Postcard from Trotsky Head,Hailing Poussin, Postcard from Trotsky Head, Camp Wife, 31st Pennsylvanian Infantry, camped near Washington, Forage Cap, Prosthetic, Warrior Bust, West Tennessee hog, Confederate $5 bill, Colfax 1873, Powder black infantryman, HT, Striving Union infantryman

The focus of two series of recent drawings by Terry Atkinson- Berlin, East Prussia and the Desert, 2014-17 and American Civil War 2018 is the Cold War, its residual effects on the present and its origins in the momentous events that precipitated it. The drawings are displayed over two rooms at Josey gallery, interspersed with his sculptural Grease works from the 1990s. This review is informed by a public talk between Atkinson and T J Clark.

As a founding member of the Conceptual Art group Art & Language (founded 1968) Atkinson initiated and contributed to an extensive critique of all aspects of entrenched definitions of art and its production. Notions such as ‘visual language’ and the avant-garde, were scrutinised as fallacy. His long-standing art practice as opposed to a career, in turn became critical of Conceptual Art. Considering its forms to have deteriorated into a corporate style and the group Art & Language into a caucus concerned with writing its own history, he re-established his individual practice in 1974. In this highly personal body of work Atkinson’s paintings, drawings and constructions are deliberately and intrinsically rendered critical through the method by which they are made and by unusually extended titles or captions. Painting for Atkinson does not mean a return to old orders of painting convention, nor a ‘new spirit in painting’ but an investment of conceptual critique into visual work.

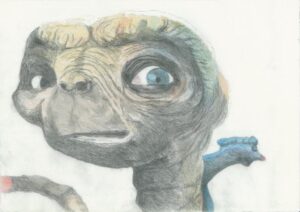

In this show the viewer is confronted with an array of interwoven historical fragments that combine real and fantastical triggers of meaning. The Berlin series depicts WW2 Russian and German soldiers drawn from archival photographs, in various states of engagement with war, including terror and bewilderment. Presented alongside this imagery there is a close-up portrait of E.T. entitled: Berlin, East Prussia and the Desert: Study 4. After having watched Hitler’s corpse burn, ET and a blue cousin await their ship, Berlin, April 1945. What might be described as a number of Goyaesques also enter the fray of drawn imagery, a sinister floating figure from Goya’s Asmodea, 1819, points towards what appears to be an Albert Speer Nazi monument. On the opposite wall of the gallery a still life displays military regalia as Soviet trophy souvenirs, including a capsule of Pervitin, known as ‘pilot salt’- crystal meth given to the Luftwaffe to allow them to remain awake during long flights.

When asked by Clark how he chose these images and subject matter for this WW2 history painting, Atkinson replied that he could remember the last three years of that war. Recalling the headlines in August 1945, after the two atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan, he said he realised ‘this is something that cooked-up the Cold War but it was there long before WW2 in shroud form’. At 16/17 years old he understood that it was the Russians who destroyed the Wehrmacht and that the casualties in the East were astronomical. His parents’ lives spanned two world wars, their histories are generational and the imagery therefore comes from life experiences. Atkinson produces drawings on his living room table, not in a studio. They are ‘low tech’, made with coloured pencils in a sketchbook. As a record of historical events they form a diaristic timeline:

‘I was 13 when Stalin died.

I was 18 when the Cuban revolution was achieved.

I was 17 when I first heard and embraced Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly.

I was 50 when the wall came down.’

Atkinson’s choice of imagery combines this family testimony and its confrontation with the extreme violence of war critically when conveyed as phantasmagoria.

In response to the suggestion that Goya is not contemporary with this particular past, Atkinson stated that the importance of Goya is that he deals with the reviled aspects of human experience. He continues, ‘Goya’s Capricos, (series of etchings) is the main feed into this work; they have absurdity and heavy caricature’. T J Clark also has an interest in mirroring contemporary events using art historical models. His recent book, Heaven on Earth, Painting and the Life to Come, 2018 considers medieval and early modern painters as a method of coming to terms with the bizarre politics of our era. He writes, ‘We live in an age of revived and intensified religion, and of wars in which once again God’s will is invoked to deadly effect’. Atkinson’s use of Goyaesques recalls out-of-time references that expose a fragile and febrile European Modernism as capricious absurdity.

Time travel in Atkinson’s drawings is further invoked through the recurring image of the fictional Hollywood character E.T. wandering in and out of the imagery of war zones. Clark observed that E.T. might be taken to represent Atkinson himself as an alien visitor observing the effects of European Modernism. A figure that is made both strange and familiar, this fantastical creature exudes suburban sentimentality. In Berlin, East Prussia and the Desert: Study 4, … E.T. is swaddled in a towel, a close-up of his face taking up most of the drawing, he is faintly smiling and looking upwards. E.T. is as Clark said, ‘a fully historically conscious baby’. Subtly in the landscape behind E.T. a tiny smouldering fire is visible which alludes to the burning bodies of Joseph and Magda Goebbels following their suicide. Atkinson reminds us that Magda Goebbels poisoned eight children in an act that was compliant with Hitler’s suicide pact with his officers as WW2 came to an end. The moral dynamic of this juxtaposition of smiley-face E.T. with matter-of-fact murder of children amply displays a definition of the tragicomic as a relentless, hysterically fluctuating, limbo.

The process employed by Atkinson as a ‘history recording artist’ is to ‘test and try’ juxtapositions of his various accumulated images garnered from many sources: archival photographs, records of oral history and testimony plus the ‘celluloid heroes’ of his grandchildren’s era etc. He says ‘WW2 had a big impact because it froze part of my childhood’.

As he works he thinks about historical junctures and what is being ‘projected forward by these drawings’. The results reveal moments of historical import that function not as commemorative statues that may affirm existing contradictions of a culture, but as moments that focus contested events that remain vital.

The American Civil War series of drawings has this sense of historical accumulation, akin to small museums of drawn images that exhibit the sensibility of a collector of Americana. The captions often use abbreviations that form lists of historical figures, items or events. “H.T”. for example is Harriet Tubman, “R.P” is Rosa Parks. In Study 69, “J.C.” and “T.S.” refer to John Carlos and Tommie Smith drawn from a photograph, they are depicted with raised black-gloved hands in Black Power salutes on the podium, receiving their medals at the 1968 Mexican Olympic Games. The defiant gesture, made as the American National Anthem played, caused intense silence in the stadium.

American Civil War Study 73, combines the mutilated heads of soldiers from Atkinson’s Trotsky postcard series from the early 1980s with various American Civil War drawn references, listed here from the caption: Camp Wife 31st Pennsylvania Infantry; Prosthetic, Powder Black Infantryman’ etc. In this drawing Atkinson conjoins the stark effects of both Civil Wars, Russian and American, using diverse and satirical combinations that allude to the complexity of a Cold War ‘time-traveller’s’ point of view. Atkinson yet maintains, despite the overdetermined imagery a consistent, underlying political position.

Bart Simpson, E.T., the Jedi and the Goyaesques sometimes make for a poignant, jarring effect yet in other instances a single image is ample. The larger-scale portrait with full caption: American Civil War: Study 32 Lost part of his left ear at 2nd Bull Run, August 1862. Here, in this drawing, weary on a break from the front-line trenches at Petersburg, January 1865. Infantryman of the 97th New York, is a case in point. That this figure could also be imagined as a time-traveller across eras is evident in the context of this show and through our knowledge of the continued impact of this history. The half-length portrait of a uniformed soldier stands out against a dark background. His belt buckle identifies him as a Union soldier with pistol and holster across the tunic. The focus is on the face divided into two expressions. The left eye stares out at the viewer, a dilated stare, while the right eye reveals his determined attitude. Immediately his aim must have been to survive. Ultimately however, the contribution of this Union soldier, in terms of a battle of the history of ideas was to clarify and affirm an enlightened, antislavery stance. Drawn as mentioned, in coloured pencils in a sketch book on the dining room table, the mark- making, repetitive diagonal strokes to build up surface, is somewhat similar to a high school observational method of drawing. Early success with drawing and representation could be said to persist here as a personal enlightenment. Read in the context of Atkinson’s oeuvre however, this method amusingly also derides and questions values received through art education. By combining ideologically naive, untrained or proletarian drawing methods with ideologically sophisticated marks devolved from a significant knowledge of modern art Atkinson pushes a critical reading.

Many of the presuppositions of what an artist is and does, professed by British art school education in the 1960s against which Atkinson and Art & Language formed their ideas, are still in place. The notion of an artistic subjectivity critically described by Atkinson as a ‘self-confirming centre of truth’, ‘engaged in a pure visual language’, remains a hard nut to crack. More recently his critique, Avant Garde Models of the Artistic Subject, questions the efficacy of notions of artistic dissent which have been co-opted into a cyclical, contained and institutionalised mode of pseudo ‘avant garde’ practice in which novelty or gimmick substitute for the genuinely attained New. His recently-coined term, ‘Exhibitionism’, offered as one more art school ‘pick and choose’ style akin to Pointillism or Cubism, satirically emphasises the current primacy of career over serious aesthetic investigation through both theory and practice.

The Grease works, 1987-1993, which present the engineering material axle grease in three-dimensional troughs within abstract constructions are probably the most open-ended in terms of interpretation of all these works. Axle grease makes immediate reference to the greasing of machines such as tanks and cars. Displayed as art however, didacticism and ideology are also to be ‘greased’ as cultural production. Atkinson stated in the public talk with regard to the history of Ireland that ‘the idea of being British was “greasy” ‘. Regarding the relationship between visual art and language he said, ‘if grease were language it would be a proletarian grunt’.

The most memorable Greaser sculpture, though not displayed in the current show, is comprised of several troughs of axle grease placed on the floor in the shape of a Union Jack. The combination of emblem and fluid mass, precludes the complex absurdity of a private visual language, as its connotations provoke confrontation and questioning about meaning, all the more blatantly for being sculptural and prone to both physical and metaphorical spillage.

Terry Atkinson, Josey Gallery, Norwich, 27th November to 27th February 2022