Loretta Pettinato

Spring 2020 was an abnormal and far from ideal season. Certain spectral atmospheres resembled Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings, while also being comparable to the pandemics that disrupted societies in the past, such as the 17th-century Black Plague described by Alessandro Manzoni in I Promessi Sposi. We have been isolated, forced to interrupt physical contact, gripped by boredom and, at times, depression. In order to pass the long hours at home, some writers suggested keeping a diary; other artists, such as David Hockney, encouraged people to buy pencils and brushes and dedicate themselves to painting. Still others believed that the best thing to do was to let our minds wander. The spark that began my own thoughts was reading the article The Etruscan Cowboys – Owners of the South. This was about a show organized by the Archaeological Museum of Naples, which will remain open until May 31, 2021. More than 600 artifacts, mostly from necropolises, show us what objects accompanied the departed through their journey in the afterlife, while also asserting their social status.

One can admire clay balsamariums shaped like crouched deer, decorated urns, precious jewels, cladding slabs, and small bronze statues, such as the Bronzetto di offerente (The Offering Bearer) from Elba (6th-5th century BCE). According to the director of the museum, Paolo Giulierini, the exhibition aims to reconstruct a frontier history, in which Etruscans can be considered the cowboys of their times.

The origins of the Etruscans are unknown, they came either from the north or the east and were already settled in Italy by the 8th century BCE. They expanded to the south into the Campania region, where they ruled for many centuries. As I was reading this article, I remembered a journey made years ago in central Italy to explore the lands populated by the Etruscans and their necropolises, the majority of which are in Tuscany and Lazio. I recall the necropolis of Monterozzi in Tarquinia, where mounds of earth indicated the presence of hypogeums, holes dug in the turf, and very narrow stairs leading into burial chambers. I found myself in front of marvellous frescoes with brilliant colours: red for the masculine figures, white for the feminine ones, and then light blue, dark green and ochre. The walls are filled with musicians, dancers, and acrobats who bring delight to the banquets; hunting and fishing scenes, sport competitions and memories of heroic deeds. I can bring to mind the burials that particularly thrilled me: a hunting and fishing one (520 BCE), with its flying red and blue birds that filled the ochre sky, and its twisting fish that jumped in the water while being watched by the three characters; all surmounted by a joyous banquet in which the deceased is also present.

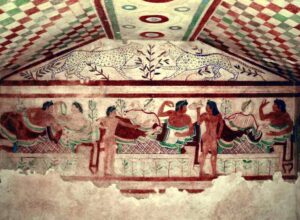

Another example is the Tomba dei Leopardi, representing a small group of feasting men guarded by two gorgeous leopards on a golden background, surrounded by colourful festoons and frames. Alongside these merry representations one can also find scenes of desperation in response to death. In the Tomba del Barone (510 BCE) the wife and children of the departed express all their pain for their loss; in the Tomba degli Auguri (530 BCE) two figures stare at a door symbolising the gateway to the underworld. Their static position seems to represent death’s inevitability, to which everybody will succumb.

My memories then take me to Volterra, whose museum holds one of Italy’s most important collections of Etruscan artifacts: alabaster urns, pottery, and several small statues such as the famous Ombra della sera (meaning ‘shadow of the night’). It is a little bronze statue with an elongated and filiform shape, which recalls long sunset shadows, hence the name given to it by the poet Gabriele d’Annunzio. It portrays a masculine figure which, in its beauty and elegance, could have been handcrafted today, while in reality it is the creation of a brilliant craftsman during the 3rd century BCE. Many contemporary artists have taken inspiration from it for their own work, such as Alberto Giacometti. Among his many pieces, we remember L’uomo che cammina (1961).

The Etruscans didn’t leave any written material. The objects used for the cult of the dead are the only means we have to study that part of their civilisation (subsumed as it was by the Romans), dedicated to art, love of life, and family relations. The archeologist T.E. Lawrence once said that “the Etruscan cities vanished as completely as flowers. Only the tombs, the bulbs, were underground”.

Translated by Laura Pettinato

Volume 35 no 3 January - February 2021