Miklos Legrady

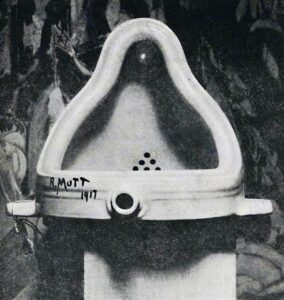

There’s a 1968 BBC interview when Duchamp said that art was discredited, he meant to get rid of art like some got rid of religion.[1] It was also the moment the penny dropped. The urinal now made sense; it says that art is to piss on, whicj really does discredit art. Such “shocking” ideas were as exciting as they were rebellious, they became all the rage but we must be warned; psychology says we eventually believe what we profess.

In time Duchamp believed his own words. He kept saying art was meaningless as a shocking marketing strategy, but repeating such statements was likely the reason he lost his motivation and stopped making art. You can only promote an idea for so long before you begin to consider that they might be true; perhaps art was meaningless and unnecessary. This was probably what stopped Duchamp.

Jasper Johns wrote that Duchamp wanted to kill art; the inevitable conclusions is that he was the first victim of his own success. Repeat something long enough, and soon enough you’ll believe it. He stopped. Johns went on to say Duchamp tolerated, even encouraged the mythology around that ‘stopping’, “but it was not like that …” He spoke of breaking a leg. “You didn’t mean to do it“[2]. He still poked and prodded at Étant donné for twenty long years in a room behind his long empty studio, , but obviously the muse was gone, and like any spurned lover she wasn’t coming back.

The art world cheered this apoptosis; does this mean we need to review peer review? Duchamp spent his last 20 years playing chess. Chess does not exercise creative functions since the moves are repetitive and their number is finite. An overview of Duchamp’s history suggests he was not as creative as he was a political theorist who adopted DADA strategies. That strategizing is there in his love of chess, which was stronger than his love of art; the art world got jilted and never saw it coming.

Duchamp was a talented artist who denied art to épaté la bourgeoisie, shock the bourgeoisie He remained relatively unknown until the 1960s when, according to Robert Storr, MOMA curator and later Dean of Fine Arts at Yale, “the art world moved from the Cedar Tavern to the seminar room”. The e problem is real because art is always action, while the academy likes to watch and seminars feast on discussion. There’s a real risk of putting Descartes before the horse.

A Duchamp myth gained traction in the academic environment with his program of intellectual art, for example that found objects were not meant to be objects seen in a gallery but subjects to be talked about in discussions. The Duchamp we know never existed, the genius who discovered new art forms; that was a tale by an art world in need of heroes. In reality, Duchamp was an artist who claimed art was unnecessary and discredited, while working as an artist in an art environment. This contradiction could not last and he was surprised to find himself unable blocked.

Contradictions also become obvious in the writing of Walter Benjamin, of Sol Lewitt, and quite a few others. Today’s internet search yields knowledge previously unknown or inaccessible, or that took months, sometimes years of inquiry by snail mail. History is as grounding as it gets. We depend on shared history for a sense of common purpose. We depend on it for context and perspective, and we expect more than spin or vested interests when it comes to historical facts.

Among curious anomalies in postmodern culture we see embedded errors, many proven wrong but never corrected. Statistically, all systems produce a degree of chaos, but such errors are kept under control by redundancy and reality checks. When that balance crosses a line the system degrades and the engine starts knocking. Political science says that your culture is your future, that means we must correct the past to fix the future. Our history could certainly use some correction.

There’s a target over Duchamp’s urinal, which wasn’t Duchamp’s to begin with. In a 1917 letter to his sister, Duchamp writes that the urinal was sent by a friend of his, a female artist who used the pseudonym R. Mutt. This was Dada artist Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven, armut means poverty in German. Duchamp likely appropriated Fountain after Elsa’s death, it was perfect for his project to discredit art; the urinal does say that art is to piss on. That is typical DADA, much like Picabia’s words in his DADA Manifesto, that “art is the opiate of idiots”. Canadian artist Michael Schreier points out that if used as mounted the urinal would piss out at you … the target is the onlooker.

Francis Naumann is a canonical Duchamp scholar who was also Duchamp’s friend, who wrote extensively on Duchamp over decades. I emailed him asking “what if the Bicycle Wheel is not a work of art”? He replied that Duchamp said it was and hundreds of experts agreed it was, so it must be. I was deeply disappointed with this superficial answer; the opinions of experts are not a convincing argument; we need to judge the reasoning behind them.

Naumann was kind enough to send me a pdf of chapter 112 of his book, The Recurrent, Haunting Ghost: Essays on the Art, Life and Legacy of Marcel Duchamp. He points to the part where Duchamp retroactively declared the Bicycle Wheel and the Bottle Rack to be works of art.[3]

It was at some point in 1913—around the time when he made his bicycle wheel assembly - that Duchamp asked himself … Peut on faire des oeuvres qui ne soient pas “d’art”? [Can one make works which are not “works of art?”]. He scrawled this question down on a sheet of paper, and wrote on the verso: 1913. In mid-January 1916, Duchamp wrote a letter to his sister Suzanne telling her all about readymades and how he intended – retroactively - to include in this same category of objects the two works he had left behind in is studio (the bicycle wheel and the bottle rack).

Duchamp resisted certain interpretations of his readymades, particularly from those who claimed they contained aesthetic features comparable to those of traditional sculpture. “I threw the bottle rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge,” he told Hans Richter in 1962, “and now they [the Neo-Dadaists] admire them for their aesthetic beauty.” In June of 1968, however, in the last televised interview before his death, Duchamp came to accept the fact that a viewer acquires a natural taste for objects seen over a prolonged period. “After twenty years, or forty years of looking at it,” he said of his Bottle Rack, “you begin to like it… That’s the fate of everything, you see?”

Naumann concludes this paragraph with his own words; “It was probably while admiring its aesthetic qualities that he wondered, to paraphrase his words, if one could make a work of art out of materials that were not customarily associated with art”. This is proof, Naumann says,, that the Bicycle Wheel is a work of art.

I emailed Mr. Naumann that no, Duchamp did not say that! He clearly and consistently rejected aesthetics so would not admire these found objects, and he would never call them art; his words are specific. “The word ‘readymade’… seemed perfect for these things that weren’t works of art, that weren’t sketches, and to which no term of art applies.”[4] “Can one make works which are not art? I wrote Francis Naumann that in the book he had written, Duchamp specifically said the Bicycle Wheel is not a work of art. Naumann never replied.

Our catalogue of errors include Sol Lewitt’s Statements on Conceptual Art, and Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, which say the idea is the most important part of art while the execution is perfunctory. Lewitt’s dissatisfaction with perfunctory execution of his own work changed his mind, but he never corrected his Statements and Paragraphs; these are now often part of the undergraduate curriculum. Logic contradicts Lewitt, saying that mastery is needed to successfully express an idea. The execution is half the equation, if not more.

Another milestone is held by Walter Benjamin, who wrote that creativity is a bourgeois delusion, and all we can expect of art is an accurate representation of reality. John Berger’s 1960s TV series and book Ways of Seeing brought a semiotic reading of and art history to the general public. Unfortunately Berger was a Marxist and Benjamin’s spiritual heir so he stumbled when he wrote that painting existed to mirror the wealth of the ruling class, but now photography does a better job and so painting is dead.

That said, the long awaited ‘death of painting’ is an unrealistic expectation. The science of nonverbal discourse dates back to an 1872 publication by Charles Darwin on the expression of emotions in humans and animals. Since then, psychologists have discerned non-verbal communication in the body language of dance, the acoustic language of music, and visual language, where a picture is worth a thousand words.

In visual art just as in music we become aware of conversations within conversations; we experience patterns, sequences, bridges, opposition and harmonies, we feel melodic, periodic, or melancholic as the work moves us. Music is a language, an acoustic language, just as visual language describes things whose subtlety is lost when explained in words. Since the intellect is but one mode, that of verbal language, art touches another level when it includes that which cannot be explained in words.

The concept of non-verbal languages turns art history upside down, as sensation data and the aesthetics that evolved with visual language all of a sudden make sense. Previously art was under a cloud as the pleasure; now aesthetics are seen as elements of visual language. This would mean painting cannot die, anymore than literature.

Such obvious historical corrections should be easy, but there’s human nature. R. A. Fisher, in a lecture on the nature of science, said the goal of science was an increase in knowledge, but when this happens it’s awkward and feelings get hurt. Those committed to the past will fight tenaciously and reject changes to their comfort zone. Max Plank wrote that advances in science happen one funeral at a time, as the old school dies off, and a new generation with no commitment to the past mistakes adopts the more sensible correction.

1-BBC 1968 Interview with Marcel Duchamp

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zo3qoyVk0GU&ab_channel=MiklosLegrady

[2] Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, An appreciation, p110, Da Capo Press.

Francis Naumann, Chapter 112, The Recurrent, Haunting Ghost: Essays on the Art, Life and Legacy of Marcel Duchamp, Readymade Press, 2012.

[3] Pierre Cabane, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, A window into something else, p48, Da Capo Press.

Miklos Legrady is writing a book that sheds light on vital art history that was swept under the rug. There’s enough to stir the pot, since in art as elsewhere winners write history. Art theory never had to face the reality checks that science did, at least until now. The sciences of psychology, linguistics, and politics have a lot to say about what art is, what was swept under the rug, and why.

Legrady’s writing and visual art are at www.legrady.com