Colin Fell

Colin Fell

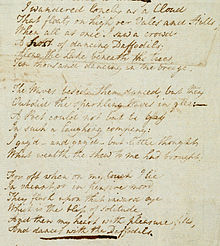

Daffodils have been much on my mind recently. This is natural enough – we’re in the midst of a glorious Cornish spring, made more glorious by the easing of lockdown. And, with the promptness we’re so privileged to enjoy here, the daffs have already been and gone, their moment of splendour in the grass already over, and where their gold has glimmered and glinted forth from gardens, fields, and road sides, the tired seed heads now nod peacefully, stoically resigned to their old age, and awaiting next year. Oh, and it’s also natural because I teach English for a living, and you can’t study English Literature without being fairly well tuned in to the charms of the daffodil. Yet like the poem which famously celebrates them, Wordsworth’s, they’re perhaps too often taken for granted, overlooked, as the showier, more ostentatious charms of the summer flowers take over, and the early Cornish spring recedes into the memory. So what better a subject could there be than Wordsworth’s little poem?

There’s a wonderful scene in the BBC’s semi improvised sitcom Outnumbered in which the teenage Jake struggles with his English homework – what does he mean he floats like a cloud, he demands in exasperation, confronted by Wordsworth’s lyric poem. What does he mean, then? The poem, so often underestimated, and judged by the contexts in which it appears – National Trust tea towels, the nation’s favourite poems (which usually means the ones that people of a certain age can remember from school, and quite possibly never really liked that much) – is really, I think, a little study in mystical experience, and badly in need of better PR.

The famous opening, in which the poet wanders, famously, “lonely as a cloud”, is the beginning of the experience – imagine our narrator as detached, dreamily unengaged, and think of the key word lonely, which doesn’t necessarily mean he was alone, of course. In fact, there’s good reason to think he wasn’t – his sister Dorothy recorded a walk illuminated by sights of daffodils on 15 April 1802, and her diary entry sounds uncannily like her brother’s poem; I’m writing this, incidentally, on the 219th anniversary of that walk! History does not record, by the way, how Dorothy felt either about William’s apparent loneliness on their walk, or his unacknowledged filching of some of his best lines from her diary entry.

Anyway, this detached mood vanishes, as William and/or Dorothy (I somehow imagine her going ahead first) round a corner, because there they are, those daffodils, “all at once”, as he puts it, a “crowd, a host”. I love the “all at once” – it means we can forget all those images we might have of tame, passive flowers and kindly poets bending down to admire them – this is a sudden, dramatic experience, live and in the moment, almost a shock. Suddenly he’s not so lonely – notice how his perception changes in a moment from seeing them as a “crowd”, suggesting he sees the flowers as alive, anthropomorphised, but still fairly anonymous, to the more welcoming “host”. Wordsworth, unlike his friend Coleridge, was no Christian; nature was his religion, but it’s tempting to think, in this Easter poem, that in the rising of the golden flower from the recently dead earth, he saw something almost like a sacrament, the raising of the host as symbol of rebirth – winter was long and harsh in the Lake District. Blake, whom Wordsworth considered mad, but interesting, wrote that if we could open the doors of perception, we would see nature as it really is, infinite; in the early 1960s the ageing Aldous Huxley took to mescaline to try to prove this for himself, but for the 32-year-old Wordsworth there was no need – he talks of ten thousand daffodils, but essentially they’re a glimpse into the infinite – they “stretch in never ending line”. It’s the last stanza that proves that this poem is more than it might seem at first sight. Wordsworth fast forwards to another time, another place, a room where he lies on his couch “in vacant or in pensive mood”, and the miracle happens – the flowers “flash upon his inward eye, that is the bliss of solitude”. “Flash” is such a great verb here – demeaned in our time by connotations of exhibitionism and photography, here it has a sense of radiance, and, again, an almost violent theatricality. And they’ve been transformed – no longer flowers, but symbols of the divine in nature, as he sees them not with his eye, but with his “inward eye”; in a sort of secular transubstantiation, they’ve become a part of his soul. Notice “solitude”, too – unlike his earlier loneliness, he’s now on his own; but not, as the experience of the flowers, remembered, sustains him. And where before now he floated, now he dances, in a sort of ecstatic communion with the rhythms of the natural world he so loved. “And dances with the daffodils” has a wonderfully sturdy iambic pulse about it; I imagine a vigorous, pagan dance, earthy and energetic, certainly not a civilised waltz.

And so, in the end, the poem is about memory – and as those early promises of new life slip into obscurity all around us, and meekly give way to tempestuous tulips, rambling roses and proud peonies, spare a thought for them and for Wordsworth – allow them to flash upon your inward eye and look forward to next March!

Volume 35 no 5 May / June 2021