‘Where Has Protest Music Gone?’

Jorge M. Benitez

While performing in London in 2003, the Dixie Chicks – a country music group now known only as the Chicks – upset their conservative fans when lead singer Natalie Maines said, ‘We’re ashamed the President of the United States is from Texas.’ Although the ensuing firestorm did not involve protest music, it signaled an uncertain future for the genre. The age of offended sensibilities had arrived, and the Dixie Chicks learned that the price of discursive honesty was public nullification.

Music is an art form. Public protest is political action. They can be combined; but there is a price, and the outcome is never guaranteed. Protest is also a difficult word. We think that we know what it means to express a grievance or support a cause. The reality is less clear-cut.

In the English-speaking world, with its Enlightenment traditions of toleration and free expression, the word protest has an almost sacred meaning. We learn in childhood that we have rights that allow us to lodge public complaints against institutions and officials. We cite the Magna Carta as a harbinger of democracy while forgetting its aristocratic nature. In the United States, we invoke the First Amendment to the Constitution while trying to deny our fellow citizens the right to contradict us. In truth, most of us know little about the word protest, its Latin roots, or its links to a uniquely Western world-view steeped in Greco-Roman thought.

In Latin, to protest is to ‘assert positively’ or to ‘declare in public.’ Rhetorical rebellion is as old as Socrates’ mockery of his judges and as legendary as the Promethean defiance of the gods. Such historical tales and myths comprise the essence of the West: a spirit of individual revolt against the will of deities, princes, tribes, and mobs. What does this mean for protest music in the twenty-first century?

If a pro-choice group were to sing satirical songs mocking the religious beliefs of the pro-life camp, could they be prosecuted as hate mongers? The answer depends on the jurisdiction. As social critic and free speech advocate Jacob Mchangama explains: ‘In Scotland, a sweeping new hate crime bill expands the prohibition against ‘stirring up hatred’ to include a raft of new groups – recalling the Spanish Inquisition – even applies to speech uttered in private homes.’ Some of the ‘groups in question happen to be religious. How can anyone discuss the threat of Iranian theocracy or Christian nationalism under the circumstances? How does a state that privileges the anti-Enlightenment sensibilities of patriarchal misogynists over Western principles of toleration and free expression determine that a critical discourse constitutes hate speech? Mchangama notes that ‘In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt had warned that if hate speech prohibitions were embedded in human rights law, ‘any criticism of public or religious authorities might all too easily be described as incitement to hatred and consequently prohibited.’ This realization should be chilling to feminists and LGBTQ+ advocates whose main opponents are mostly theocratic. In 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt could not have imagined that universal human rights could someday be sacrificed to religious authoritarianism in the name of social justice. By the late 1990s, a latter-day Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Western social justice movements and anti-Western religious activists would put the future of free expression in doubt. Although few could see it at the time, protest music was on notice. If the rest of the West follows the Scottish ‘Hate Crime and Public Order Bill,’ then free speech will be on life support.

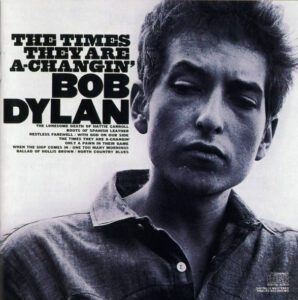

Although protest songs had existed as satirical ballads and folk chronicles for centuries, the genre of protest music would not emerge until the arrival of broadcast radio. Whether it was Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit in 1939, Woody Guthrie singing working class folk anthems such as This Land Is Your Land in the 1940s, or Merle Haggard singing Okie from Muskogee in 1969, protest music could be as ambiguous and satirical as it was earnest. From the 1930s through the 1960s, Jazz, folk, country, and rock and roll touched the shared cultural values of an otherwise racially and ideologically divided people. Racists were not above listening to Billie Holiday even when one of her songs condemned lynching. Nor were Woody Guthrie or Merle Haggard dismissed because their songs could withstand conflicting interpretations. Was This Land Is Your Land a patriotic anthem of American unity or a call for Stalinist collectivization? Was Okie from Muskogee a mockery of Goldwater conservatism or an ode to heartland values? Did Bob Dylan sympathize with the Weather Underground because one of his lyrics inspired their name? Could John Lennon’s Imagine be played in today’s Scotland given its lyrics?

‘Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too’

Imagine is a critique of nationalism, religion, and the wars they inspire. Perhaps unintentionally, it questions the identity fetishism that religion and nationalism often engender. Yet Imagine is performed as an inclusive peace anthem in gatherings that seem oblivious to its message. Is it a protest song—if so, against what…against the protesters? Similar questions apply to Lennon’s Revolution, a song that seemed to mock the rebellious Parisian hipsters of 1968. Whether or not Lennon cast doubt on the legitimacy of revolutionary struggle and the hypocrisy of self-styled French café Maoists or was merely advocating pacifism, his songs raise questions about the viability of commercial protest music.

In 1971, John Lennon and Yoko Ono released Happy Xmas (War Is Over), a sincere and very catchy anti-war song that has since become a standard. It seemed softer than the more militant Imagine, but it still cast doubts on the genre of commercial protest music, something altogether different from the working-class folk songs of previous decades. Does the public understand songs such as Imagine or Happy Xmas (War Is Over)? Do they change minds? Do they sway public policy, or does the market merely co-opt them and thereby neutralize them? Such questions inform the core of what could be called Che-Guevara-T-shirt-syndrome, a condition that destroys revolutionary pretensions through market-driven co-option. How many people give up their bourgeois lives after seeing or wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt? How many Americans turned against the Vietnam War after hearing Happy Xmas (War Is Over)? The only clear answer is that, as with artists, dead revolutionaries sell better than live ones. In the record business, the underlying cause is merely value added.

Broadway expanded the issue of market co-option in 1967 with Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical. Its depiction of anti-war hippie edginess was a commercial success with buttoned-down audiences. One of its hit songs, Easy to Be Hard, asked whether people ‘who care about strangers, who care about evil and social injustice’ were actually capable of empathy and compassion on a personal level. In retrospect, the question becomes even more pertinent when seen against the failures of the counterculture in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. The peace movement that had tied its moral fortunes to the utopian ideals of universal love and justice in the 1960s had failed to act in the face of the Khmer Rouge’s Cambodian genocide and the recriminations of the North Vietnamese against the South Vietnamese in 1975. The resulting impression was one of indifference at best and collusion at worst, not unlike the impression that Charles Lindbergh gave in the 1930s after his flirtations with the Nazi regime and his involvement with the isolationist, anti-progressive, and anti-Semitic America First Committee.

Whatever moral capital the protesters of the 1960s had accumulated had already started to evaporate when Angela Davis refused to support the Prague Spring in 1968 on the grounds that the Communist government of Alexander Dubček had betrayed the Soviet Bloc by implementing liberal reforms. In an open letter chastising Angela Davis, Czech Communist Party member Jiri Pelikan wrote that the inclusion of non-Communists among Czech political prisoners ‘must not be a pretext for indifference to their fate. In Czechoslovakia we have paid dearly for our failure to understand that liberty is not divisible and that injustice toward opponents will in the end turn itself back on those who commit injustice. If liberty is taken away from some of the people it will soon die for the rest.’ Pelikan’s pleas did not resonate among the American protest crowd for whom liberty was not only ‘divisible’ but contextual.

Along with the end of the Prague Spring and the disastrous Paris student riots, the summer of 1968 witnessed the working class cops of Chicago turning against the Yippies, whom they regarded as privileged brats, with nearly homicidal ferocity as the Democratic convention performed a meltdown on national television. Protest music, no matter how well written and performed, could not stand up to the fact that the left was dissolving its ties to the workers that had once defined it. From that moment onward the counterculture would give way to the Culture Wars. What had once been the proletariat became the backbone of a right-wing movement at odds with a cultural elite that no longer spoke the language of workers, farmers, or the poor. The days of folk singing union organizers were gone. The coalition that had elected FDR four times was dead. Tragically, the new reality did not reflect a right-wing victory but a progressive capitulation. It was no accident that after 1968 the protest soundtrack of Czech, Polish, and other Eastern European dissidents came not from the American folk scene but from the bad boys of British Rock such as The Rolling Stones and Cream. Understandably, the young people who had confronted Soviet tanks on the streets of Prague in 1968 were in no mood for the empty promises of love and peace from Haight-Ashbury in San Fransisco.

Yet despite its less-than-glorious fate, much of the protest music of the 1960s expressed what the French call universalisme. Today, the French sense of universal solidarity defies the neo-segregation that defines twenty-first-century social justice movements. Denying the humanity of the oppressor makes it impossible to develop a genre that aspires to universal justice. If anything, whenever calls for justice are framed in binary terms, they soon degenerate into calls for revenge. Universalisme gives way to revanchisme. With all the force of Newtonian physics, action begets reaction as victims and oppressors trade places cyclically. Jacobinism replaces toleration and civility as the revolution surrenders to affinity groups that play into the hands of a segregationist extreme right wing. Worse still, progressive calls for authenticity and purity unwittingly echo National Socialist demands for Aryan unity. Given the murderous history of the quest for purity and authenticity, the postmodern recycling of the Volksgemeinschaft cannot pretend to be progressive or remotely anti-fascist merely because the Volk in question have been oppressed or marginalized. Does this imply the end of protest music?

If anything, this should be a time of great protest music. The sociopolitical stakes are high, the threat of global war is strong, environmental degradation is increasing, and the grievances of racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities are even more pertinent than in the 1960s. Where, then, are the songs? Why did the upheavals of 2020-21 not result in memorable anthems that could speak to the world? Why did the attempted coup of January 6, 2021, not inspire Dylan-esque ballads? Where is the Odetta, the Joan Baez, the Buffy Sainte-Marie, or the Joni Mitchell of our time? Where is the raw, sandpaper voice of a new Janis Joplin? There is no single answer to these questions, although they point in an unwelcome direction.

Free expression and canonical knowledge have been under increasing assault from the left and the right since the 1990s. Diversity no longer includes the possibility of cultural crossover. The left dismisses the Western Canon as colonialist while the right fears it as anti-Christian. Conversely, regardless of race, social background, or educational level, the musical activists of the past shared cultural values steeped in the Western Canon. African-Americans combined European church music with their surviving West African traditions. Jazz musicians like Duke Ellington were experienced in classical music. The Bible and Shakespeare informed blues and country musicians alike. Eastern European Jews joined with Irish musicians who in turn defied convention to jam with Black colleagues. The society was racist and cruel, but the culture was vibrant and gave rise to a generation that wrote and performed the anthems of the 1960s. This is not an exercise in nostalgia. Today there are gifted and courageous young musicians ready to grab the baton, but the times are against them, and they struggle to overcome the mediocrity thrust upon them by a combination of capitalist interests and cultural absurdity in an increasingly uncertain, authoritarian climate of digital abuse. The slightest indiscretion can lead to ostracism or violence. Under the circumstances, it is understandable that 2020 should not have led to a rebirth of protest music.

The current obsession with appropriate-versus-inappropriate words and symbols is inimical to artistic creativity. Satire, an essential ingredient in protest art, requires irreverence and wit, two qualities in short supply among today’s social justice puritans. In 2020, Black Lives Matter, ANTIFA, and the Democratic Socialists did not grasp that the Gramsci-Marcuse challenge to perceived cultural hegemony only worked in an environment of unified communications. The Internet is too atomized - too pixelated to sustain agitation propaganda beyond the narrow, short-lived goals of disembodied activists and other ethereal creatures imprisoned in a digital Faraday cage. Once the monuments—the offending symbols of oppression—had been toppled after the murder of George Floyd, the activists were left without rallying points, without a physical connection to the system they longed to overthrow. Furthermore, they remained unfocused and unable to understand the depth of the emerging backlash, and they could only resort to increasingly arcane theoretical arguments lost on a population tired of scolding harangues about its moral failings. Without what Marshall McLuhan called the ‘hot’ medium of radio, their ability to transmit incessantly over the Internet became irrelevant. Yes, they could reach millions, but those listeners and readers already knew the message. Their digital printing presses morphed into self-cancelling instruments of impotent rage mired in the false notion that words alone can change the world. They had, in a sense, returned to a time before 1453, before Gutenberg and his press. Under the circumstances, there was no way to create and project any kind of protest music that could transcend the limited interests of increasingly narrow and often self-marginalized identities. Nor could they overcome their self-righteous hatred of free speech.

In reference to free speech among ANTIFA activists, American historian Mark Bray wrote, ‘When I asked the Dutch anti-fascist Job Polak [about free speech], he shrugged and smirked saying it was a ‘non-argument that we never felt we should engage with…you have the right to speak but you also have the right to be shut up!’’ Job Polak professed contempt for discursive tolerance, political pluralism, and the concept of a loyal opposition. Speech belonged to the winners in a zero-sum struggle. Given what Bray chronicled in ANTIFA, even if the anti-fascists could produce a Berthold Brecht or a Bob Dylan, they would ‘shut’ him ‘up’ over some linguistic transgression that offended one group or another. Like the Social Democrats, Socialists, and Communists of the dying Weimar Republic, they could only turn against one another while smugly dismissing the real fascists as morally and intellectually inferior. The path seemed open to a right-wing revival of the protest song…if only by default.

In the summer of 2023, a Virginia–born singer-songwriter named Oliver Anthony released a song on YouTube titled Rich Men North of Richmond. Conservatives and the extreme right embraced the song as a lament on the plight of the white working class oppressed by a wealthy metropolitan elite. His conservative fans failed to mention that the economic abandonment came mostly from the right. As Kenan Malik wrote in an article in The Guardian, ‘Rich Men North of Richmond expresses individualized resentment. It is a resentment not towards bosses or the capitalist class, as in the old songs but, as has become fashionable today, towards a nebulous political elite, defined as much by its cultural alienness as by its economic power.’ The ‘individualized resentment’ that Malik addressed is the great affliction of a narcissistic age that pays lip service to vague notions of collective pain while conflating individual entitlement with the common good. Since August of 2023, Anthony has been cagey about his song and his politics. He projects a type of volskisch simplicity that imparts a feeling of down-to-earth honesty worthy of respect from city slickers. But where does he truly stand? Does he even know?

Anthony’s artistic and political intentions may never be known. The only certainty is that Rich Men North of Richmond became a protest song for a segment of society unhappy with their role in it. In that sense, he may have unintentionally written a great anthem after all—an anthem for a looming self-pitying, all-white, economically and culturally stressed segment of our present day society.