A Meditation on a Divided Hemisphere

Jorge Miguel Benitez

I was not born a citizen of the United States, yet I have been an American from birth.

Why does the word American seem to apply exclusively to the people of the United States? Do we not all live in the Americas? The French, Germans, and Spanish are all Europeans. The Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans are all Asians. Yet only in the Western Hemisphere does one country claim a continental-hemispheric title with little to no question from the rest of the world. The issue is far from academic. In fact, it affects every aspect of Anglo-American relations with the rest of the Americas and even the world.

oil on canvas, 112” x 185” (284 x 470 cm)

Most Spanish-English dictionaries translate the word estadounidense as American. That is not its true meaning. Estadounidense means Unitedstatian. Of course, there is no such word as Unitedstatian in the English language. Although used infrequently, estadounidense also exists in French as états-unien. With such a differentiation in mind, I went to Lima, Peru, as a Cuban-born estadounidense. More importantly, I went without reductive or orientalist expectations.

Who can claim an American identity? How do we even begin to understand the meaning of a label based on the name of an early sixteenth-century Florentine business agent named Amerigo Vespucci? Where do we place the currently fashionable notion of decolonization centuries after the Western acculturation of most of the Peruvian population? Can an artist be Peruvian while finding inspiration in the New York School or in the Italian Renaissance? Should we surrender the Spanish language because it came from Europe? I addressed these questions with my Peruvian interlocutors. They, in turn, provided insights that ran against the current anti-European grain without diminishing any of the Peruvian totality.

Like the rest of Latin America, Peru shares a Western database with Europe, the United States, and Canada. Spanish is a Western Romance language with ancient Latin roots. Roman Catholicism, the dominant religion in Peru and one of the oldest continuous Christian faiths, is Western and has Judeo-Hellenic roots. Even the term Latin America is built on links to the Latin European countries of France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. My Peruvian hosts made clear that only in a Manichean scheme of absolute good and evil could Peru be decolonized. They informed me that Peruvians, ranging from Mario Vargas Llosa to the person on the street, cannot sever their ties to the Spanish Conquest or to Europe without destroying a crucial part, not of their identity, but of their being, something altogether distinct from a mere label. Only those non-Spanish-speaking Peruvians in the most far-flung hinterlands could break away from Western contamination without losing some part of themselves. This left the problem of the Conquest - the first contact with Europeans. Should all European influences be purged because they arrived with Francisco Pizarro? Without exception, the answer was, no.

All conquests are cruel. From the Spanish conquests of Mexico, in 1519, and Peru, in 1532, to the English conquests of Virginia and Massachusetts in 1607 and 1620 respectively, the act of invading and claiming someone else’s land is never benign. The greatest difference between the two European imperialist giants lies in the spin of the facts. Spain, founder of the world’s empire to circle the globe, called its actions La Conquista, the Conquest. By contrast, the English invasions of Virginia and Massachusetts have gone down in history as settlements.

Conquest-versus-settlement is a subject that goes to the heart of a philosophical divide between Anglo-Saxon America and Latin America. We discussed the issue at length in Lima. How do we address the syncretism, however imperfect, of the Latin south with the seemingly endlessly repackaged segregation of the Anglo-Saxon north? Despite its cruelty, the Conquest led to mixed populations and cultures, if for no other reason than necessity. Conversely, the settlement of the North American East Coast involved displacement and segregation from the start. Not only did the English disapprove of intermixing, they invaded with entire families in a process of wholesale replacement – not genocide in the modern sense but an easily rationalized form of passive eradication. The effects of the approach can still be felt in a United States that, to Latin Americans, appears obsessed with labels, categorizations, and systemic separation through the encouragement of affinity groups and notions of purity and authenticity. The approach is essential to denying the Western-ness of Peru and of Spain itself. When combined with the still powerful influence of the Black Legend that depicts anything related to Spain as evil and degenerate, it remains challenging for Latin American artists and intellectuals to break free from the cage of Rousseau-esque innocence and exoticism. We are painfully aware that our links to Spain are used against us as proof of our inadequacy. Throughout my brief stay in Lima, the question of American doubts concerning Peru’s Western-ness elicited the following response: “Do they expect us to wear feathers?”

I understood the Peruvian response. On more than one occasion I, too, have been expected to wear feathers. My visit to Lima reinforced the chasm that divides Anglo-Saxon America from Latin America – a chasm I often witness in my life as a Latin American of European descent who moves easily from one language and culture to another. The chasm is contrived and reflects Old World animosities rooted in the Reformation, dynastic struggles, and imperial ambitions. In the late 1990s, during a talk on Latin American art, I heard a respected New York art critic say, “Fortunately, we are witnessing the last vestiges of degenerate Spanish influence in Latin America.” She advocated a return to indigenous traditions as the only authentic expression for the region. In response to her overt contempt, I asked, “As a descendant of those degenerate Spaniards, I would like to know why the United States insists on fighting the Spanish Armada when Great Britain and Spain are no longer enemies?” She apologized and gave no further explanation. I was not surprised.

The anti-Iberian bias usually goes hand-in-hand with a lingering anti-Catholicism that depicts Western-ness as the progressive result of the Protestant emphasis on individuality. It is a cynical fiction that dismisses Southern Europe and half of the Western Hemisphere. While in Lima, I had an opportunity to address the issue with Pedro Pablo Alayza, executive director of MACLima, the Lima Museum of Contemporary Art. He did not mince words. Peru cannot escape its history or the present. As a scholar and museum director with a background in anthropology, he explained the futility of a romantic yearning for a pre-Columbian past. “The contemporary is everywhere. The contemporary is the present,” he said with a smile. Then he explained the collusion between the surviving Inca nobility and the Spanish in the aftermath of the Conquest. The event was far from a clear-cut struggle between innocence and cruelty. Few of the players had clean hands. The result was something unforeseen, something that still defies easy answers. Peru, he added, can and should celebrate all of its history and its myriad cultures, but it cannot purge the West from its spirit or blood. He then contrasted the Mexican attacks on the cosmopolitanism of Carlos Fuentes with the measured Peruvian acceptance of the equally cosmopolitan Mario Vargas Llosa and his critique of what he calls the “archaic utopia.” The point was clear: Peru cannot return to its pre-Columbian past.

Over the course of two meetings with Pedro Pablo Alayza, we discussed what it means to be a Peruvian artist in a global culture. Our consensus was that the answer lies in the hands of the individual artist. In short, there is no obligation to make Peruvian art, which, in any case, is increasingly difficult to define. The issue reminded me of a curator who once told me that my paintings were not “Cuban enough.” Why should they be? My birthplace should not be a cultural cage. Do we expect Pollock to paint Wyoming landscapes or De Kooning to paint like Rembrandt? I would later revisit the issue in a meeting with one of Peru’s greatest living painters.

As we spoke, Pedro Pablo Alayza and I agreed that national identity is only one aspect of a total human experience. The background to the conversation was the lingering influence of the indigenista movement and its calls for art rooted in native forms, experiences, and aspirations. Is that even possible for a cosmopolitan resident of Lima? Yes, but at the risk of falling into kitsch or a mockery of indigenous people. As Vargas Llosa posits in The Archaic Utopia (La utopía arcaica), the indigenista movement played an important role in calling attention to the plight of indigenous peoples, but it can also trap the artist in a kind of revolutionary romanticism that omits the dark truths of pre-Columbian life. To that end, Vargas Llosa stresses that there was never an indigenous utopia free from exploitative hierarchies. Pre-Columbian life was far from benign or idyllic.

A few days after my first meeting with Pedro Pablo Alayza, I raised the issue with the Peruvian writer Carlos Schwalb. He smiled when I asked about the question of Peruvian Western-ness as he explained that it was uneven and contextual. His answer made sense given the size of the country and the diversity of its people. We then proceeded to a larger question, namely, what constitutes the West? Urban Peru did indeed possess a Western database, but it did not experience the Enlightenment. My native Cuba had also not experienced the Enlightenment. We agreed that the absence of full engagement with the main currents of the Enlightenment had seriously damaged Latin America and Spain itself. Without an early encounter with British empiricism and French skepticism, it became more difficult to enter modernity. Today, the West is inseparable from the Enlightenment. The Spanish unwillingness to participate in the Enlightenment was central to the ongoing Latin American tragedy. The region bypassed the Age of Reason and jumped into the fire of Romanticism and the French Revolution. It experienced the seductively irrational idealism of Jean-Jacques Rousseau without the sobering benefit of John Locke, Voltaire, David Hume, Denis Diderot, or Adam Smith. The names were known, but their ideas remained mysterious and difficult to implement. I had witnessed the damage that Rousseau-inspired Jacobinism had inflicted on my fellow Cubans. Talking about it in Lima with a Peruvian intellectual added weight to the issue.

As the conversation continued, Carlos Schwalb explained his interest in the pre-Socratic philosophers. This led me to ask him about Nietzsche, and he enthusiastically admitted his admiration for both the German philosopher and Albert Camus. He confessed to being a Francophile. Did that make him less Peruvian? Was I less Cuban for speaking English and French? Why did we not play our assigned roles as noble savages? We dove into the questions and ended with a critique of Platonic idealism and the dangers of utopian ideologies. I then realized that our conversation would have been very difficult thirty years earlier. Latin American discourse was changing into something more nuanced and elegant: a far cry from the hysterical nationalism of Cuba and Venezuela and the knee-jerk anti-Americanism of a resentful intelligentsia unable to explain postcolonial failures without resorting to foreign scapegoats.

My meetings and conversations occurred against the backdrop of a twenty-first-century city immersed in the Digital Age. From skyscrapers near the bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean to manicured parks and colonial plazas, I witnessed a city at ease in its historically-culturally-and-technologically-layered skin. The overlap of influences ranging from Spanish Baroque and French Beaux Arts to the International Style reminded me of Madrid and Barcelona. The inside of the mudéjar – Islamic patterned – dome within a side chapel in the Basilica of San Francisco drove home the positive power of contradictions. Why should a Catholic Basilica not have a Muslim dome built by indigenous Peruvians? This set the stage for my encounter with a genteel artist and intellectual, the painter Ramiro Llona.

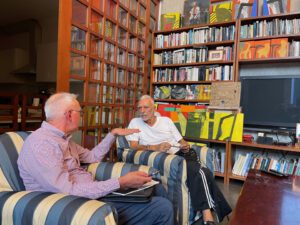

A long colonial courtyard with an equally long pool to its left led to the studio of Ramiro Llona. The approximately twenty-foot-high walls were covered with paintings and books. Bach concerti sounded from the hidden speakers. Javier Tapia, my Peruvian friend, fellow artist, and host, had arranged the meeting. He introduced me to Ramiro. The tall, lean gentleman immediately put me at ease. We sat down and entered into a nearly four-hour-long conversation that covered art, philosophy, politics, and, of course, Latin America.

Ramiro Llona is a true modernist, an artist steeped in the European canon and the New York School. German and Abstract Expressionism and the European avant-garde are in his blood. He also visits Italy yearly and is passionate about Vittore Carpaccio and Piero della Francesca. As he spoke, I listened intently as if the mudéjar dome had come to life and said, “You see, I am Peruvian after all. I embody all these contradictions.” He studied and worked in New York. He speaks English fluently. He, too, is a hemispheric American. Yet he is also thoroughly Peruvian and therefore aware of his country’s history and challenges. We spoke at length about what it means to be cosmopolitan in a world that seems to be regressing toward provincialism. Is Latin American Eurocentrism a form of treason? Is cosmopolitanism an exclusively Anglo-American privilege? Listening to Ramiro eloquently articulate, in flawless Castilian, the complexities at play once again drove home the absurdity of reductive answers. I left his studio with a gift of two beautiful books about his work and a sense of wonder and hope. Latin America was not a hinterland after all.

My conversations with Carlos Schwalb, Ramiro Llona, Pedro Pablo Alayza, and Peruvians across the social spectrum made me wonder if the United States was still a Western country. Had it become a technologically advanced banana republic? Had it turned its back on the Enlightenment? The ideological neuroses that plague American campuses have led to the export of identity politics with imperialist fervor. These latter-day intellectual conquistadors insist that the rest of humanity must embrace American notions of nationality and race if it wants to be hip, relevant, and socially just. The other choice is American religious fundamentalism and Ayn Rand-inspired capitalism. Neither choice is palatable or useful. What civic or moral lessons could Latin America learn from a country where a disgruntled president had attempted a coup d’état, the civilian population had more guns than most national armies, civil rights were under judicial threat, large segments of the population no longer trusted science, religiosity had become a political litmus test, angry states threatened secession, and infinitely mutable personal identities were more important than the plight of the working class? Contemporary American imperialism, from Left to Right, consisted of exporting the poison of identity politics to regions that had outgrown tribalism and post-colonial immaturity. Latin American intellectuals were able to read Foucault in the original French without Anglo-American explanations. Spanish speakers did not need linguistic advice from American identity theorists. Nor did we need lessons in authenticity and race consciousness. We knew who we were without the benefit of Nazi-like notions of purity and authenticity. I had felt and known these things before traveling to Lima. My Peruvian conversations confirmed them.

courtesy Jorge Benitez

Would my experience have been more authentically Peruvian had I gone to Cusco or Machu Picchu? Despite their importance, those marvelous sites do not define the totality of the country, its culture, or its people. Lima, the capital, serves as an enriching and sobering introduction to a complex society in a very complex continent. More importantly, my experience in Lima was authentically American, which to say, of the Americas. In less than two weeks, while speaking nothing but Castilian and laughing with my Peruvian hosts as they gently taught me about their amazing country, I learned that I was indeed an American rather than merely an estadounidense. I was a citizen of the Americas – a citizen of the entire hemisphere. I was also thoroughly Western, as were my Peruvian hosts. These seemingly disparate cultural threads were as interwoven as the ancient textiles in the Museo Amano. Peru taught me to embrace everything – to appropriate everything – because, in the end, there is only one database … the Human database. That is the true gold of the Inca Empire, the Viceroyalty of Peru, and its modern descendent, the Republic of Peru.